Large-size versions of illustrations are available by clicking on them.

General table of contents — Narrative in Index — Itineraries in Index

TRAVELS

AND DISCOVERIES

IN

NORTH AND

CENTRAL AFRICA.

VOL. I.

London:

Printed by Spottiswoode & Co.

New-street Square.

TRAVELS

AND DISCOVERIES

IN

NORTH

AND CENTRAL

AFRICA:

BEING A

JOURNAL OF AN EXPEDITION

UNDERTAKEN

UNDER THE AUSPICES OF H.B.M.’S

GOVERNMENT,

IN THE YEARS

1849-1855.

BY

HENRY BARTH, Ph.D., D.C.L.

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL AND ASIATIC

SOCIETIES,

&c. &c.

IN FIVE VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

LONGMAN, BROWN, GREEN, LONGMANS, & ROBERTS.

1857.

The right of translation is reserved.

TO THE RIGHT

HONOURABLE

THE EARL OF CLARENDON, K.G.,

G.C.B.

ETC. ETC. ETC.

HER MAJESTY’S SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN

AFFAIRS,

THESE VOLUMES,

CONTAINING AN ACCOUNT OF

TRAVELS AND DISCOVERIES IN NORTH AND CENTRAL

AFRICA,

MADE UNDER HIS LORDSHIP’S AUSPICES,

ARE,

IN GRATEFUL ACKNOWLEDGMENT FOR MANY ACTS OF KINDNESS,

Dedicated,

BY HIS OBLIGED AND FAITHFUL SERVANT,

THE AUTHOR,

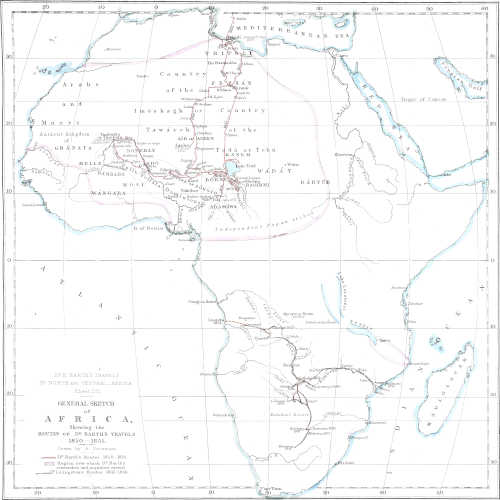

DR. BARTH’S TRAVELS

IN NORTH AND CENTRAL AFRICA

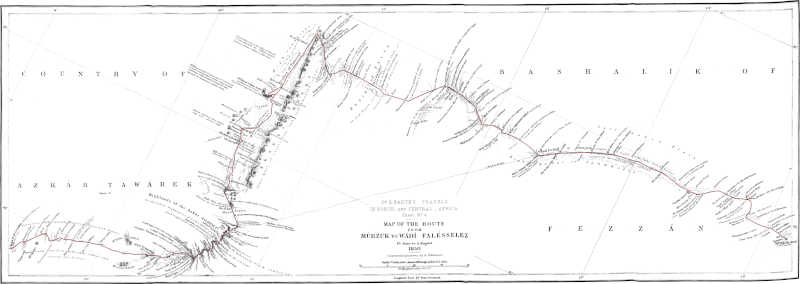

Sheet No. 1.

GENERAL SKETCH

of

AFRICA,

Showing the

ROUTES OF DR. BARTH’S

TRAVELS

1850-1855.

Drawn by A. Petermann.

Engraved by E. Weller.

London, Longman & Co.

[vii]PREFACE.

On the 5th of October, 1849, at Berlin, Professor Carl Ritter informed me that the British Government was about to send Mr. Richardson on a mission to Central Africa, and that they had offered, through the Chevalier Bunsen, to allow a German traveller to join the mission, provided he was willing to contribute two hundred pounds for his own personal travelling expenses.

I had commenced lecturing at the University of Berlin on comparative geography and the colonial commerce of antiquity, and had just at that time published the first volume of my “Wanderings round the Mediterranean,” which comprised my journey through Barbary. Having undertaken this journey quite alone, I spent nearly my whole time with the Arabs, and familiarized myself with that state of human society where the camel is man’s daily companion, and the culture of the date-tree his chief occupation. I made long journeys through desert tracts;[viii] I travelled all round the Great Syrtis, and, passing through the picturesque little tract of Cyrenaica, traversed the whole country towards Egypt; I wandered about for above a month in the desert valleys between Aswán and Kosér, and afterwards pursued my journey by land all the way through Syria and Asia Minor to Constantinople.

While traversing these extensive tracts, where European comfort is never altogether out of reach, where lost supplies may be easily replaced, and where the protection of European powers is not quite without avail, I had often cast a wistful look towards those unknown or little-known regions in the interior, which stand in frequent, though irregular, connection with the coast. As a lover of ancient history, I had been led towards those regions rather through the commerce of ancient Carthage, than by the thread of modern discovery; and the desire to know something more about them acted on me like a charm. In the course of a conversation I once held with a Háusa slave in Káf, in the regency of Tunis, he, seeing the interest I took in his native country, made use of these simple but impressive words: “Please God, you shall go and visit Kanó.” These words were constantly ringing in my ears; and though overpowered for a time by the vivid impressions of interesting and picturesque countries, they echoed with renewed intensity as[ix] soon as I was restored to the tranquillity of European life.

During my three years’ travelling I had ample opportunity of testing the efficacy of British protection; I experienced the kindness of all Her Britannic Majesty’s consuls from Tangiers to Brúsa, and often enjoyed their hospitality. It was solely their protection which enabled me to traverse with some degree of security those more desert tracts through which I wandered. Colonel Warrington, Her Majesty’s consul in Tripoli, who seems to have had some presentiment of my capabilities as an African explorer, even promised me his full assistance if I should try to penetrate into the interior. Besides this, my admiration of the wide extension of the British over the globe, their influence, their language, and their government, was such that I felt a strong inclination to become the humble means of carrying out their philanthropic views for the progressive civilization of the neglected races of Central Africa.

Under these circumstances, I volunteered cheerfully to accompany Mr. Richardson, on the sole condition, however, that the exploration of Central Africa should be made the principal object of the mission, instead of a secondary one, as had been originally contemplated.

In the meantime, while letters were interchanged[x] between Berlin, London, and Paris (where Mr. Richardson at that time resided), my father, whom I had informed of my design, entreated me to desist from my perilous undertaking, with an earnestness which my filial duty did not allow me to resist; and giving way to Dr. Overweg, who in youthful enthusiasm came immediately forward to volunteer, I receded from my engagement. But it was too late, my offer having been officially accepted in London; and I therefore allayed my father’s anxiety, and joined the expedition.

It was a generous act of Lord Palmerston, who organized the expedition, to allow two foreign gentlemen to join it instead of one. A sailor was besides attached to it; and a boat was also provided, in order to give full scope to the object of exploration. The choice of the sailor was unfortunate, and Mr. Richardson thought it best to send him back from Múrzuk; but the boat, which was carried throughout the difficult and circuitous road by Múrzuk, Ghát, Aïr, and Zínder, exciting the wonder and astonishment of all the tribes in the interior, ultimately reached its destination, though the director of the expedition himself had in the meanwhile unfortunately succumbed.

Government also allowed us to take out arms. At first it had been thought that the expedition ought to go unarmed, inasmuch as Mr. Richardson had made[xi] his first journey to Ghát without arms. But on that occasion he had gone as a private individual, without instruments, without presents, without anything; and we were to unite with the character of an expedition that of a mission,—that is to say, we were to explore the country while endeavouring at the same time to establish friendship with the chiefs and rulers of the different territories. It may be taken for granted that we should never have crossed the frontier of Aïr had we been unarmed; and when I entered upon my journey alone, it would have been impossible for me to proceed without arms through countries which are in a constant state of war, where no chief or ruler can protect a traveller except with a large escort, which is sure to run away as soon as there is any real danger.

It may be possible to travel without arms in some parts of Southern Africa; but there is this wide difference, that the natives of the latter are exclusively Pagans, while, along all those tracts which I have been exploring, Islamism and Paganism are constantly arrayed against each other in open or secret warfare, even if we leave out of view the unsafe state of the roads through large states consisting, though loosely connected together, of almost independent provinces. The traveller in such countries must carry arms; yet he must exercise the utmost discretion in using[xii] them. As for myself, I avoided giving offence to the men with whom I had to deal in peaceful intercourse, endeavouring to attach them to me by esteem and friendship. I have never proceeded onwards without leaving a sincere friend behind me, and thus being sure that, if obliged to retrace my steps, I might do so with safety.

But I have more particular reason to be grateful for the opinion entertained of me by the British Government; for after Mr. Richardson had, in March, 1851, fallen a victim to the noble enterprise to which he had devoted his life, Her Majesty’s Government honoured me with their confidence, and, in authorizing me to carry out the objects of the expedition, placed sufficient means at my disposal for the purpose. The position in which I was thus placed must be my excuse for undertaking, after the successful accomplishment of my labours, the difficult task of relating them in a language not my own.

In matters of science and humanity all nations ought to be united by one common interest, each contributing its share in proportion to its own peculiar disposition and calling. If I have been able to achieve something in geographical discovery, it is difficult to say how much of it is due to English, how much to German influence; for science is built[xiii] up of the materials collected by almost every nation, and, beyond all doubt, in geographical enterprise in general none has done more than the English, while, in Central Africa in particular, very little has been achieved by any but English travellers. Let it not, therefore, be attributed to an undue feeling of nationality if I correct any error of those who preceded me. It would be unpardonable if a traveller failed to penetrate further, or to obtain a clearer insight into the customs and the polity of the nations visited by him, or if he were unable to delineate the country with greater accuracy and precision, than those who went before him.

Every succeeding traveller is largely indebted to the labours of his predecessor. Thus our expedition would never have been able to achieve what it did, if Oudney, Denham, and Clapperton had not gone before us; nor would these travellers have succeeded so far, had Lyon and Ritchie not opened the road to Fezzán; nor would Lyon have been able to reach Tejérri, if Captain (now Rear-admiral) Smyth had not shown the way to Ghírza. To Smyth, seconded by Colonel Warrington, is due the merit of having attracted the attention of the British Government to the favourable situation of Tripoli for facilitating intercourse with Central Africa; and if at present the river-communication along the Tsádda or Bénuwé[xiv] seems to hold out a prospect of an easier approach to those regions, the importance of Tripoli must not be underrated, for it may long remain the most available port from which a steady communication with many parts of that continent can be kept up.

I had the good fortune to see my discoveries placed on a stable basis before they were brought to a close, by the astronomical observations of Dr. Vogel[1], who was sent out by Her Britannic Majesty’s Government for the purpose of joining the expedition; and I have only to regret that this gentleman was not my companion from the beginning of my journey, as exact astronomical observations, such as he has made, are of the utmost importance in any geographical exploration. By moving the generally-accepted position of Kúkawa more than a degree to the westward, the whole map of the interior has been changed very considerably. The position assigned by Dr. Vogel to Zínder gives to the whole western route, from Ghát through the country of Ásben, a well-fixed terminating point, while at the same time it serves to check my route to Timbúktu. If, however, this topic be left out of consideration, it will be found that the maps made by me on the journey,[xv] under many privations, were a close approximation to the truth. But now all that pertains to physical features and geographical position has been laid down, and executed with artistic skill and scientific precision, by Dr. Petermann.

The principal merit which I claim for myself in this respect is that of having noted the whole configuration of the country; and my chief object has been to represent the tribes and nations with whom I came in contact, in their historical and ethnographical relation to the rest of mankind, as well as in their physical relation to that tract of country in which they live. If, in this respect, I have succeeded in placing before the eyes of the public a new and animated picture, and connected those apparently savage and degraded tribes more intimately with the history of races placed on a higher level of civilization, I shall be amply recompensed for the toils and dangers I have gone through.

My companion, Dr. Overweg, was a clever and active young geologist; but, unfortunately, he was deficient in that general knowledge of natural science which is required for comprehending all the various phenomena occurring on a journey into unknown regions. Having never before risked his life on a dangerous expedition, he never for a moment doubted that it might not be his good fortune to return home[xvi] in safety; and he therefore did not always bestow that care upon his journal which is so desirable in such an enterprise. Nevertheless almost all his observations of latitude have been found correct, while his memoranda, if deciphered at leisure, might still yield a rich harvest.

One of the principal objects which Her Britannic Majesty’s Government had always in view in these African expeditions was the abolition of the slave-trade. This, too, was zealously advocated by the late Mr. Richardson, and, I trust, has been as zealously carried out by myself whenever it was in my power to do so, although, as an explorer on a journey of discovery, I was induced, after mature reflection, to place myself under the protection of an expeditionary army, whose object it was to subdue another tribe, and eventually to carry away a large proportion of the conquered into slavery. Now, it should always be borne in mind that there is a broad distinction between the slave-trade and domestic slavery. The foreign slave-trade may, comparatively speaking, be easily abolished, though the difficulties of watching over contraband attempts have been shown sufficiently by many years’ experience. With the abolition of the slave-trade all along the northern and south-western coast of Africa, slaves will cease to be brought down to the coast; and in[xvii] this way a great deal of the mischief and misery necessarily resulting from this inhuman traffic will be cut off. But this, unfortunately, forms only a small part of the evil.

There can be no doubt that the most horrible topic connected with slavery is slave-hunting; and this is carried on not only for the purpose of supplying the foreign market, but, in a far more extensive degree, for supplying the wants of domestic slavery. Hence it was necessary that I should become acquainted with the real state of these most important features of African society, in order to speak clearly about them; for with what authority could I expatiate on the horrors and the destruction accompanying such an expedition, if I were not speaking as an eye-witness? But having myself accompanied such a host on a grand scale, I shall be able, in the third volume of my narrative, to lay before the public a picture of the cheerful comfort, as well as the domestic happiness, of a considerable portion of the human race, which, though in a low, is not at all in a degraded state of civilization, as well as the wanton and cruel manner in which this happiness is destroyed, and its peaceful abodes changed into desolation. Moreover, this very expedition afforded me the best opportunity of convincing the rulers of Bórnu of the injury which such a perverse system entails upon themselves.

[xviii]But besides this, it was of the utmost importance to visit the country of the Músgu; for while that region had been represented by the last expedition as an almost inaccessible mountain-chain, attached to that group which Major Denham observed on his enterprising but unfortunate expedition with Bú-Khalúm, I convinced myself on my journey to Ádamáwa, from the information which I gathered from the natives, that the mountains of Mándará are entirely insulated towards the east. I considered it, therefore, a matter of great geographical importance to visit that country, which, being situated between the rivers Shárí and Bénuwé, could alone afford the proof whether there was any connection between these two rivers.

I shall have frequent occasion to refer, in my journal, to conversations which I had with the natives on religious subjects. I may say that I have always avowed my religion, and defended the pure principles of Christianity against those of Islám; only once was I obliged, for about a month, in order to carry out my project of reaching Timbúktu, to assume the character of a Moslim. Had I not resorted to this expedient, it would have been absolutely impossible to achieve such a project, since I was then under the protection of no chief whatever, and had to pass through the country of the fanatic and barbarous[xix] hordes of the Tawárek. But though, with this sole exception, I have never denied my character of a Christian, I thought it prudent to conform to the innocent prejudices of the people around me, adopting a dress which is at once better adapted to the climate and more decorous in the eyes of the natives. One great cause of my popularity was the custom of alms-giving. By this means I won the esteem of the natives, who took such a lively interest in my wellbeing that, even when I was extremely ill, they used to say, “ʿAbd el Kerím[2] shall not die.”

I have given a full description of my preparatory excursion through the mountainous region round Tripoli; for though this is not altogether a new country, anyone who compares my map with that of Lyon or Denham, will see how little the very interesting physical features of this tract had been known before, while, at a time when the whole Turkish empire is about to undergo a great transformation, it seems well worth while to lay also the state of this part of its vast dominions in a more complete manner before the European public.

Of the first part of our expedition there has already appeared the Narrative of the late Mr. Richardson, published from his manuscript journals,[xx] which I was fortunately able to send home from Kúkawa. It is full of minute incidents of travelling life, so very instructive to the general reader. But from my point of view, I had to look very differently at the objects which presented themselves; and Mr. Richardson, if he had lived to work out his memoranda himself, would not have failed to give to his Journal a more lasting interest. Moreover, my stay in Ágades afforded me quite a different insight into the life, the history, and geography of those regions, and brought me into contact with Timbúktu.

Extending over a tract of country of twenty-four degrees from north to south, and twenty degrees from east to west, in the broadest part of the continent of Africa, my travels necessarily comprise subjects of great interest and diversity.

After having traversed vast deserts of the most barren soil, and scenes of the most frightful desolation, I met with fertile lands irrigated by large navigable rivers and extensive central lakes, ornamented with the finest timber, and producing various species of grain, rice, sesamum, ground-nuts, in unlimited abundance, the sugar-cane, &c., together with cotton and indigo, the most valuable commodities of trade. The whole of Central Africa, from Bagírmi to the east as far as Timbúktu to the west (as will be seen in my narrative), abounds in these products. The natives of these regions not only weave their[xxi] own cotton, but dye their home-made shirts with their own indigo. The river, the far-famed Niger, which gives access to these regions by means of its eastern branch the Bénuwé, which I discovered, affords an uninterrupted navigable sheet of water for more than six hundred miles into the very heart of the country. Its western branch is obstructed by rapids at the distance of about three hundred and fifty miles from the coast; but even at that point it is probably not impassable in the present state of navigation, while, higher up, the river opens an immense highroad for nearly one thousand miles into the very heart of Western Africa, so rich in every kind of produce.

The same diversity of soil and produce which the regions traversed by me exhibit, is also observed with respect to man. Starting from Tripoli in the north, we proceed from the settlements of the Arab and the Berber, the poor remnants of the vast empires of the middle ages, into a country dotted with splendid ruins from the period of the Roman dominion, through the wild roving hordes of the Tawárek, to the Negro and half-Negro tribes, and to the very border of the South African nations. In the regions of Central Africa there exists not one and the same stock, as in South Africa; but the greatest diversity of tribes, or rather nations, prevails, with idioms entirely distinct.

[xxii]The great and momentous struggle between Islamism and Paganism is here continually going on, causing every day the most painful and affecting results, while the miseries arising from slavery and the slave-trade are here revealed in their most repulsive features. We find Mohammedan learning engrafted on the ignorance and simplicity of the black races, and the gaudy magnificence and strict ceremonial of large empires side by side with the barbarous simplicity of naked and half-naked tribes. We here trace a historical thread which guides us through this labyrinth of tribes and overthrown kingdoms; and a lively interest is awakened by reflecting on their possible progress and restoration, through the intercourse with more civilized parts of the world. Finally, we find here commerce in every direction radiating from Kanó, the great emporium of Central Africa, and spreading the manufactures of that industrious region over the whole of Western Africa.

I cannot conclude these prefatory remarks without expressing my sincere thanks for the great interest shown in my proceedings by so many eminent men in this country, as well as for the distinction of the Victoria medal awarded to me by the Royal Geographical Society. As I may flatter myself that, by the success which attended my efforts, I have encouraged further undertakings in these as well as in other quarters of Africa, so it will be my greatest[xxiii] satisfaction, if this narrative should give a fresh impulse to the endeavours to open the fertile regions of Central Africa to European commerce and civilization.

Whatever may be the value of this work, the Author believes that it has been enhanced by the views and illustrations with which it is embellished. These have been executed with artistical skill and the strictest fidelity, from my sketches, by Mr. Bernatz, the well known author of the beautiful “Scenes in Æthiopia.”

I will only add a few words relative to the spelling of native names,—rather a difficult subject in a conflux of languages of very different organization and unsettled orthography. I have constantly endeavoured to express the sounds as correctly as possible, but in the simplest way, assigning to the vowels always the same intonation which they have in Italian, and keeping as closely as possible to the principles adopted by the Asiatic Society. The greatest difficulty related to the “g” sound, which is written in various ways by the Africans, and puzzled even the Arabic writers of the middle ages. While the “k” in North Africa approaches the g in “give,” it takes the sound of it entirely in the Central African languages. On this ground, although I preferred writing “Azkár,” while the name might have been almost as well written “Azgár;” yet further into the interior the application[xxiv] of the g, as in “Ágades,” “Góber,” and so on, was more correct. The ع of the Arabs has been expressed, in conformity with the various sounds which it adopts, by ʿa, ʿo and ʿu; the غ by gh, although it sounds in many words like an r; ج by j; the چ, which is frequent in the African languages, by ch.

The alphabet, therefore, which I have made use of is the following:—

Vowels.

- a as in cat.

- á „ father.

- ʿa (not English) not unlike a in dart.

- e as in pen.

- é like the first a in fatal.

- i as in it.

- í „ ravine.

- o „ lot.

- ó „ home.

- ʿo (not English) not unlike o in noble.

- u as in put.

- ú „ adjure, true.

- ʿu not unlike oo in doom.

- y, at the end of words, instead of i.

Diphthongs.

- ai as i in tide (ay at the end of words).

- oi (oy), as in noise.

- au (aw), as ow in now.

Consonants.

- b as in beat.

- d „ door.

- f[3] „ fan.

- g as in got.

- j[4] „ join.

- k „ keep.

- l „ leave.

- m „ man.

- n „ not.

- ñ „ the Spanish “campaña,” like ni in companion, onion.

- p[3] „ pain.

- r „ rain.

- s „ son.

- t „ tame.

- v „ vain.

- w „ win.

- y „ yet.

- z „ zeal.

Double Consonants.

- gh as in ghost, and the g in grumble.

- ks as x in tax, excise.

- kh as ch in the Scotch word loch.

- th as in tooth.

- ts as in Betsy.

- ng as in wrong.

[xxv]A few slight discrepancies in the spelling of names will, I trust, be excused, the printing having already commenced before I had entirely settled the orthography I would adopt.

HENRY BARTH, Ph.D.

St. John’s Wood, London,

May 1. 1857.

[1]Some details will be considered in a Memoir to be subjoined at the end of this work. It is to be hoped that Dr. Vogel’s calculations themselves may be received in the meantime.

[2]“ʿAbd el Kerím,” meaning “Servant of the Merciful,” was the name which I thought it prudent to adopt.

[3]p, ph, f, in many African languages, are constantly interchanged, the same as r and dh, r and l.

[4]No distinction has been made between the different sounds of j.

[xxvii]CONTENTS

OF

THE FIRST VOLUME.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Page | |

| From Tunis to Tripoli | 1 |

| The First Start. — The Passage of the Syrtis. — Little Progress. — Trials of Temper. — Our Companions. — An Old Friend. — Reach Tripoli. | |

| CHAP. II. | |

| Tripoli. — The Plain and the Mountain-slope; the Arab and the Berber | 17 |

| An Excursion. — Arab Encampments. — Commencement of the Hilly Region. — The Plateau. — Turkish Stronghold. — Berber Settlements. — The Picturesque Fountain. — Wádí Welád ʿAli. — Khalaifa. — Beautiful Ravine. — Um e’ Zerzán. — Enshéd e’ Sufét. — Roman Sepulchre. — Kikla. — Wádí Kerdemín. — Rabda. — Kasr Ghurián. — Mount Tekút. — Kasr Teghrínna. — Hanshír. — Wádí Rummána. | |

| CHAP. III. | |

| Fertile Mountain Region rich in ancient Remains | 51 |

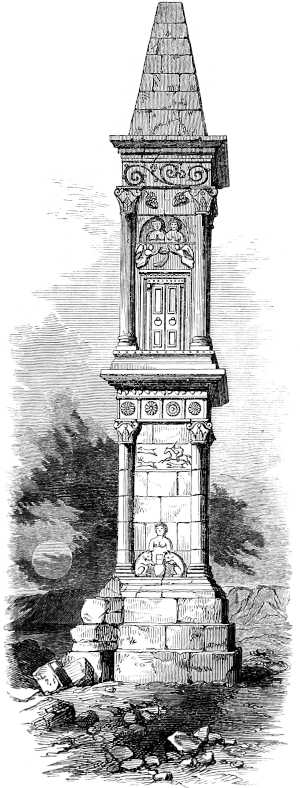

| Wádí Rán. — Jebel Msíd. — Singular Monuments. — Structure Described. — Conjectural Character. — Other Ancient Ruins. — Approach to Tarhóna. — The Governor’s Encampment. — Ruins near ʿAín Shershára. — Kasr Dóga. — Kasr Dawán. — Jebel Msíd — Meselláta. — Kasr Kerker. — The Cinyps. — Leptis-Khoms. | |

| [xxviii]CHAP. IV. | |

| Departure for the Interior. — Arrival at Mizda. — Remains of a Christian Church | 85 |

| The Departure. — ʿAín Zára. — Mejenín. — Wádí Haera. — The Boat crosses the Defile. — Ghurián. — Kuléba. — Roman Milestones. — Mizda. — The Eastern Village. — Jebel Durmán. — Wádí Sófejín. — Ruined Castle. — Christian Remains. | |

| CHAP. V. | |

| Sculptures and Roman Remains in the Desert. — Gharíya | 112 |

| Roman Sepulchre in Wádí Talha. — Wádí Tagíje. — Remarkable Monument. — Description of Monument. — Wádí Zemzem. — Roman Sepulchres at Taboníye. — Gharíya. — Roman Gateway. — Arab Tower. — Roman Inscription. — Gharíya e’ sherkíya. — The Hammáda. — Storms in the Desert. — End of the Hammáda. — El Hasi, “the Well.” | |

| CHAP. VI. | |

| Wádí Sháti. — Old Jerma. — Arrival in Múrzuk | 143 |

| Wádí Sháti, or Shiyáti. — Éderí and its Gardens. — Wádí Shiúkh. — Sandy Region. — Reach the Wádí. — Ugréfe. — Jerma Kadím. — The Last Roman Monument. — The Groves of the Wádí. — End of the Wádí. — Arrival at Múrzuk. | |

| CHAP. VII. | |

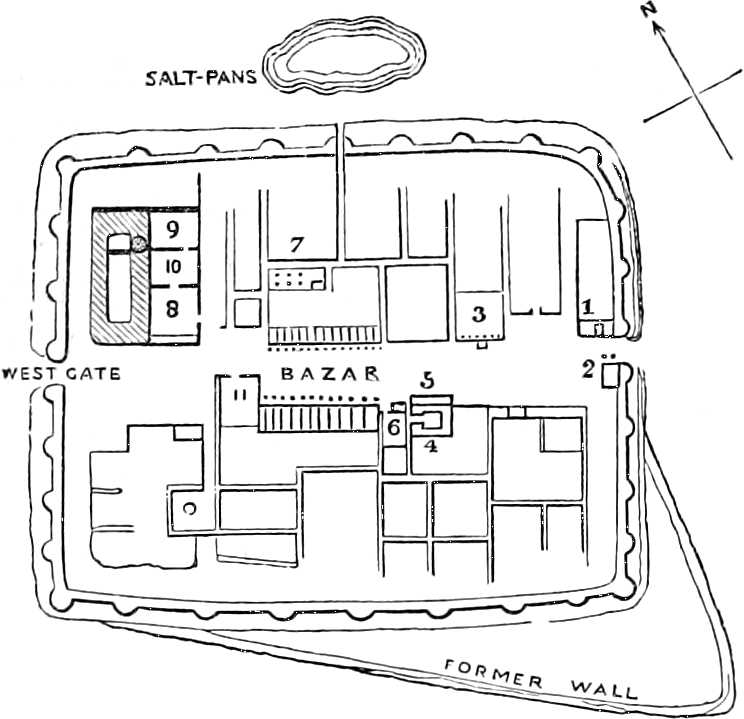

| Residence in Múrzuk | 164 |

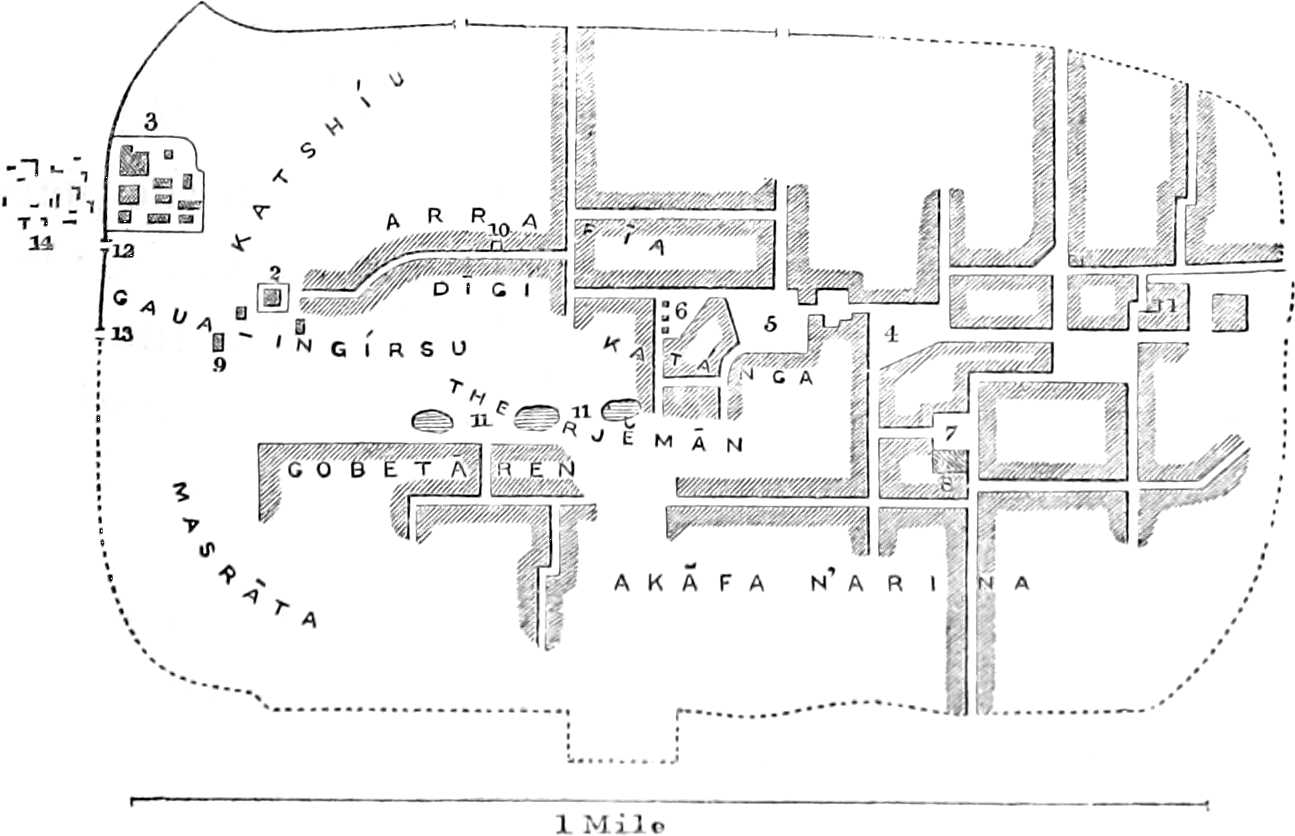

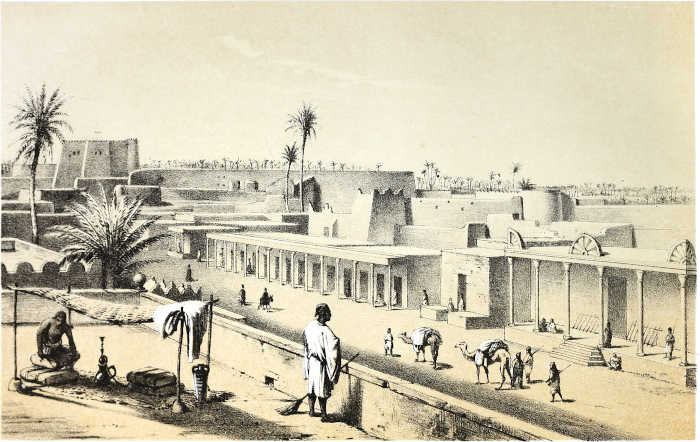

| Delay. — Character of Múrzuk. — Ground-plan of Múrzuk. | |

| CHAP. VIII. | |

| The Desert. — Tasáwa. — Exactions of the Escort. — Delay at Eláwen | 171 |

| Setting out from Múrzuk. — Tiggerurtín, the Village of the Tinýlkum. — Gathering of the Caravan. — Tasáwa. — Arrival of the Tawárek Chiefs. — Reformation of Islám. — Return to Múrzuk. — Move on finally. — Sháraba. — Wádí Aberjúsh. — Rate of Travelling. — Join the Caravan. — Tesémmak. — Wádí Eláwen. — Hatíta’s Intrigues. | |

| [xxix]CHAP. IX. | |

| Singular Sculptures in the Desert. — The Mountain-pass | 194 |

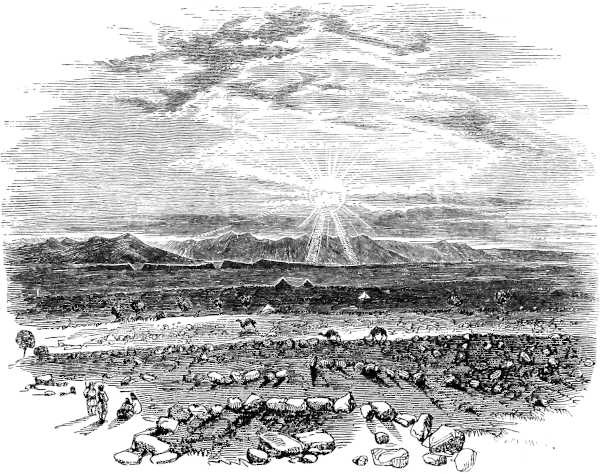

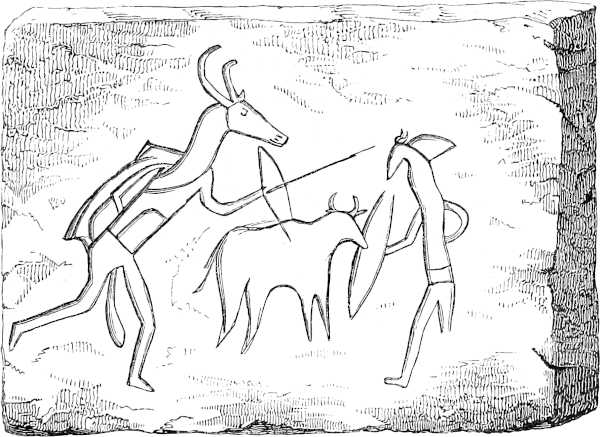

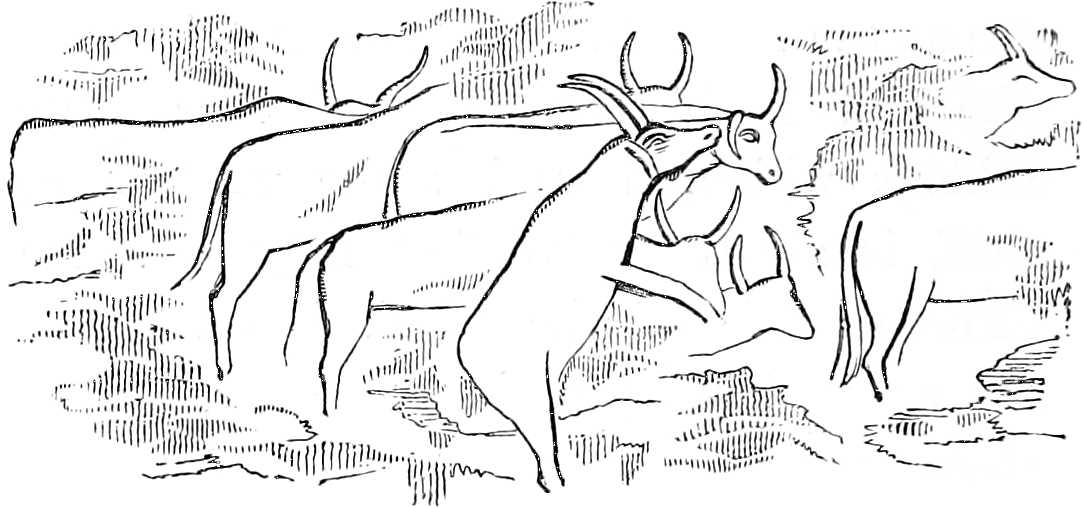

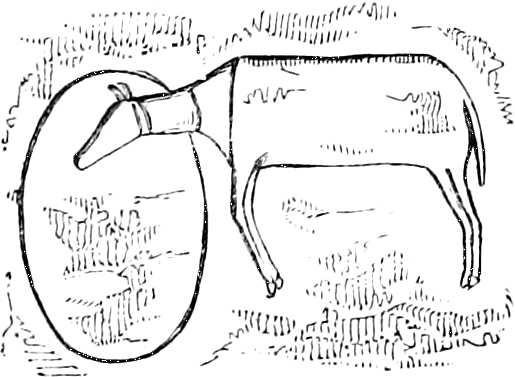

| Hatíta. — Sculptures in Telísaghé. — Subject of Sculptures, Two Deities Fighting about a Bull. — Herd of Bulls. — Cattle formerly Beasts of Burden in the Desert. — Fine Valleys. — Breaking up of the Plateau. — The Narrow Gutter-like Pass of Ralle. — Téliya. — Sérdales. — Valley Tánesof. — Mount Ídinen. — The Traveller’s Mishap. — Astray in the Desert. — The Wanderer Found. — Arrival at Ghát. | |

| CHAP. X. | |

| The Indigenous Berber Population | 223 |

| Fezzán, a Berber Country. — The Berbers. — Their Real Name Mázígh; the Name Tawárek of Arab Origin. — The Azkár. — History of the Azkár. — The Hadánarang. — Degraded Tribes. — The Imghád. — The Kél. — View of the Valley of Ghát. | |

| CHAP. XI. | |

| Crossing a large Mountain-ridge, and entering on the open gravelly Desert | 241 |

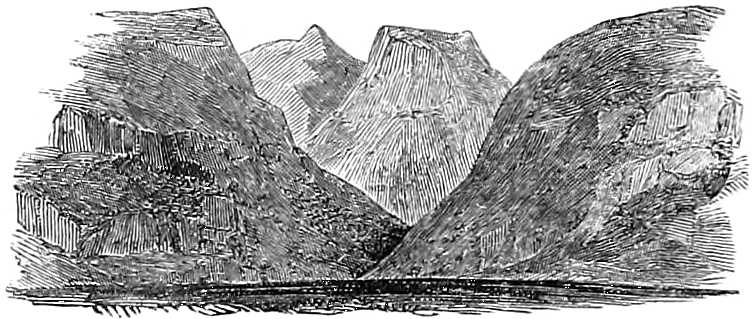

| The town of Bárakat. — The Date-groves of Bárakat and their Inhabitants. — Alpine Lake. — The Tawáti. — High Mountain-pass. — Deep Ravine of Égeri. — Threatened Attack. — Region of Granite Commences. — Desert Plain of Mariaw. — Afalésselez. — Approach to Tropical Climes. — Wild Oxen (“bagr el wahsh”) in the Desert. — Nghákeli, New Vegetation (Balanites Ægyptiaca). | |

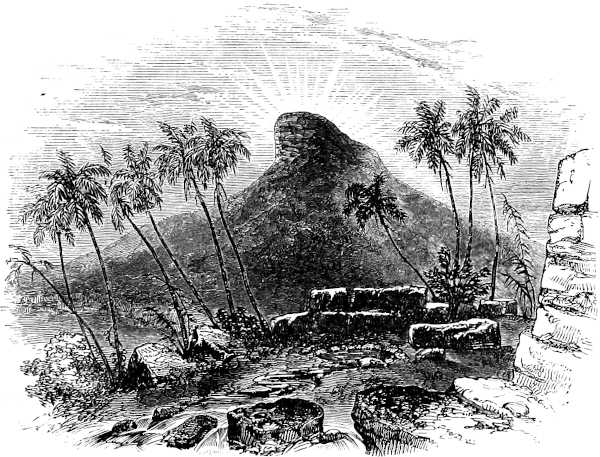

| CHAP. XII. | |

| Dangerous Approach to Ásben | 267 |

| Picturesque Peak. — Valley of Arókam. — Caravan of Merábetín. — Aséttere. — The Guineaworm. — The Caravan (at Aísala). — Berber Inscription. — Ikadémmelrang. — Peculiar Mounts. — Marárraba, the Half-way. — Bóro’s Threats. — First View of Ásben. — Asëu. — Approach of the Enemy. — Valley Fénorang. — The Freebooters. — Timázkaren. — Máket-n-Íkelán, the Slaves’ Dance. — Continued Alarms. — The Valley of Jínninau. — Pleasant Valley of Gébi. — The Capparis sodata. | |

| [xxx]CHAP. XIII. | |

| Inhabited but dangerous Frontier-region | 297 |

| Tághajít. — Character of the Borderers. — New Alarms. — Order of Battle. — Mohammed Bóro. — A Tardy Acknowledgment. — Formidable Threats. — The Compromise. — Mountains of Ásben. — Valley of Tídik. — Sad Disappointment. — Definitive Attack. — The Pillage. — Cucifera Thebaïca. — Selúfiet. — Tin-tagh-odé, the Settlement of the Merábetín. — Short State of Supplies. — A Desert Torrent. — Arrival of the Escort. — Valley of Fódet — Camel-Races. — Parting of Friends. — Valley of Afís. — New Troubles. — Arrival at Tintéllust. — The English Hill. | |

| CHAP. XIV. | |

| Ethnographical Relations of Aïr | 335 |

| The name Aïr or Ahír. — Country of the Goberáwa. — The Kél-owí. — Recent Conquest. — Descent in the Female Line. — Mixed Population. — Language. — Sections of the Kél-owí. — The Irólangh. — Tribe of the Sheikh Ánnur. — The Ikázkezan. — The Kél-n-Néggaru. — The Éfadaye. — League of the Kél-owí with the Kél-gerés and Itísan. — The Kél-fadaye. — The word “Mehárebí.” — The Kél-ferwán. — The Itísan and Kél-gerés. — Population of Ásben. — The Salt-trade.[5] | |

| CHAP. XV. | |

| Residence in Tintéllust | 360 |

| The Sheikh Ánnur’s Character. — Rainy Season. — Nocturnal Attack. — Want of Proper Food. — Preparations for Advance. | |

| CHAP. XVI. | |

| Journey to Ágades | 370 |

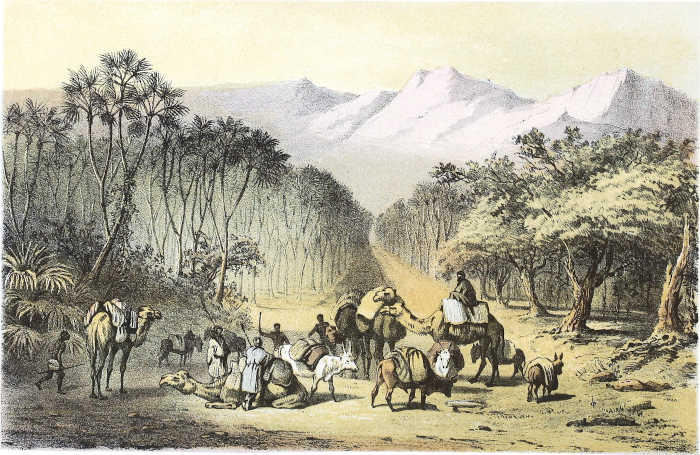

| Attempt at Bullock-riding. — Tawárek Blacksmiths. — The Double Horn of Mount Cheréka. — Ásodi and its Ruins. — Mounts Eghellál, Bághzen,[xxxi] and Ágata. — Mounts Belásega and Abíla. — The Valley Tíggeda. — The Picturesque Valley of Ásada. — The Valley of Tághist with the Ancient Place of Prayer. — Picturesque Valley of Aúderas with the Forest of Dúm-Palms. — Barbarity. — Valley Búdde. — The Natron. — The Feathered Bur. — Imghád of the Valleys. — Fertile Valley Bóghel. — The Large Báure-tree. — Arrival near Ágades. — The Troopers. — Entrance into the Town. | |

| CHAP. XVII. | |

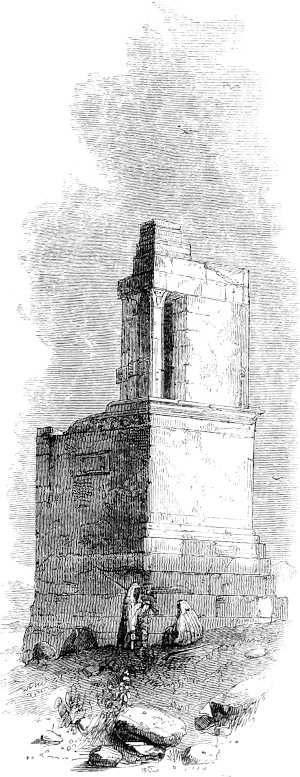

| Ágades | 397 |

| The Retail Traders from Tawát. — The Learned ʿAbdallah. — Aspect of the Town. — The Sultan’s Quarter. — Interview with the Chief. — Mohammed Bóro’s House and Family. — Markets of Ágades. — Manufactures. — Native Cavalry. — View of the Town. — The Kádhi. — Interior of Ágades. — Various Visitors. — The “Fúra,” a Favourite Drink. — Manners and Customs. — A Misadventure. — Language of Ágades the same as that of Timbúktu. — My Friend Hamma. — The Fatal Dungeon. — Ceremony of Investiture. — The Procession. — Visitors. — Rumours of War. — On Rock-Inscriptions. — Visitors again. — Episode. — Parting with Bóro. — Tailelt (Guinea-fowl) Tobes. — Áshu’s Garden. — Letters from the Sultan. — Military Expedition. — Results of the Expedition. — Interior of a House. — The Emgedesi Lady. — Ruinous Quarter. — Wanton Manners. — The Mosque and Tower. — Interior of the Mosque. — Hostile Disposition of the Kádhi. — Other Mosques in Ágades. — Enlightened Views. — Preparations for Departure. | |

| CHAP. XVIII. | |

| History of Ágades | 458 |

| Ágades not Identical with Aúdaghost. — Meaning of the Name. — The Songhay Conqueror Háj Mohammed Askiá (Leo’s Ischia). — The Associated Tribes. — Leo’s Account of Ágades. — The Ighedálen. — Tegídda or Tekádda. — Gógó and the Ancient Gold-Trade. — Position of the Ruler of Ágades. — The Sultan and his Minister. — Meaning of the word “Turáwa.” — The Town, its Population. — Period of Decline. — Ground-Plan and Quarters of the Town. — Decline of Commerce. — Market Prices. | |

| CHAP. XIX. | |

| Departure from Ágades. — Stay in Tin-téggana | 481 |

| Abortive Commencement of Journey. — The Valley Tíggeda full of Life. — Tintéllust Deserted. — Arrival in Tin-téggana. — Stay in Tin-téggana. —[xxxii] Mohammed el Gatróni. — Turbulent State of the Country. — Conversation on Religion. — Poor Diet. — Prolonged Delay. — Preparations for Starting. | |

| CHAP. XX. | |

| Final Departure for Sudán | 500 |

| Taking Leave of Tin-téggana. — Trachytic Peak of Teléshera. — Valley of Tánegat. — The Salt-caravan. — Wild Manners of the Tawárek. — Mount Mári. — Richer Vegetation. — Well Álbes. — Tebu Merchants. — Chémia. — Mount Bághzen. — Camels lost. — Rich Valley Unán. — Stone Dwellings of Kél-gerés. — Christmas Day. — Taking Leave of Hamma. | |

| CHAP. XXI. | |

| The Border-region of the Desert. — The Tagáma | 519 |

| Travelling in earnest. — Home of the Giraffe and Antilope leucoryx. — The Mágariá. — The Cornus nabeca and the Feathery Bristle. — Princely Present. — Animals (Orycteropus Æthiopicus). — The Tagáma; their Peculiar character. — The Tarki Beauty. — New Plants. — Steep Descent. — Ponds of Stagnant Water. — Corn-fields of Damerghú. — The Warlike Chief Dan Íbra. — Ungwa Sámmit. — Negro Architecture. — Name of the Hut in Various Languages. — Animal and Vegetable Kingdoms. — Horses grazing. — Arrival in Tágelel. — The Ikázkezan Freebooter. — Niggardliness of the Chief. — Towns and Villages of Damerghú. — The Haunts of the Freebooters. — Market of Tágelel. — The “Devil’s Dance.” | |

| APPENDIX. | |

| I. | |

| Route from Ágades to Sókoto | 555 |

| II. | |

| Route from Ágades to Marádi, according to the Information of the Kél-gerés Gojéri and his Companion Gháser | 556 |

| [xxxiii]III. | |

| Itinerary from Ágades to Damerghú, according to various Informants | 558 |

| IV. | |

| Route from Ágades to Bílma, according to the Émgedesi Éderi | 558 |

| V. | |

| Route from Ágades to Tawát, according to ʿAbd-Alla | 560 |

| VI. | |

| Route from Ágades to the Hillet e’ Sheikh Sídi el Mukhtár in Azawád, according to the Kél-ferwán Baina | 568 |

| VII. | |

| Fragments of Meteorological Register | 571 |

[5]“The people of Ágades at that time (the last quarter of the last century)—though Ágades then belonged to the Cashna empire—were annually permitted to load their immense caravans with the salt of Bornou, from the salt lakes of Demboo” (the Tebu country?), “the merchants of Ágades giving in return for the article a trifling price in brass and copper.”—Lucas, Proceedings of the African Association, vol. i. p. 159.

[xxxiv]LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

IN

THE FIRST VOLUME.

| MAPS. | |||

| Page | |||

| I. | General Map of Africa | to face Preface | |

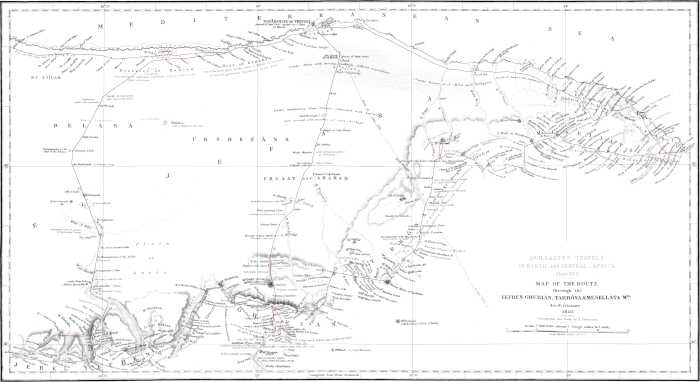

| II. | Route through the Mountainous Region of Tripoli | „ | 17 |

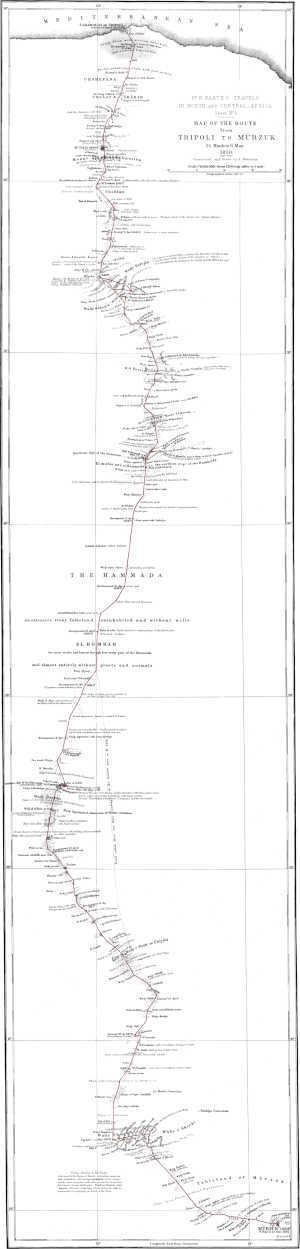

| III. | Route from Tripoli to Múrzuk | „ | 85 |

| IV. | Route from Múrzuk to Wádí Falésselez | „ | 171 |

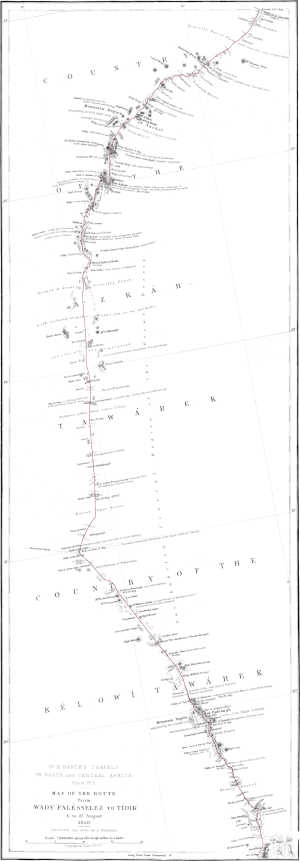

| V. | Route from Falésselez to Tídik | „ | 241 |

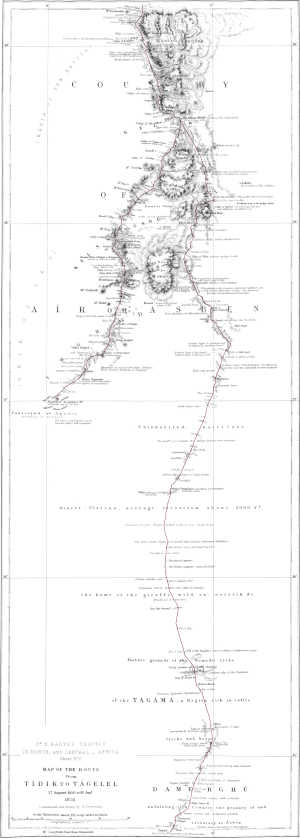

| VI. | Route from Tídik to Tágelel | „ | 297 |

| PLATES. | |||

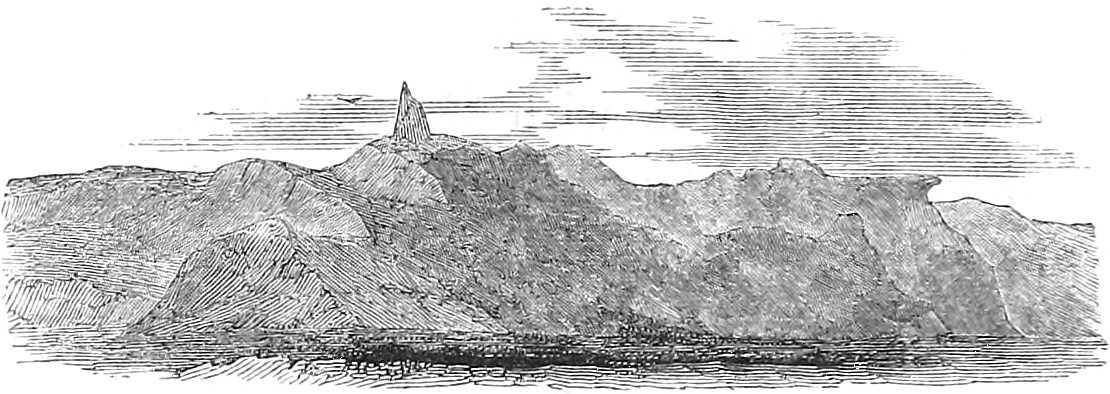

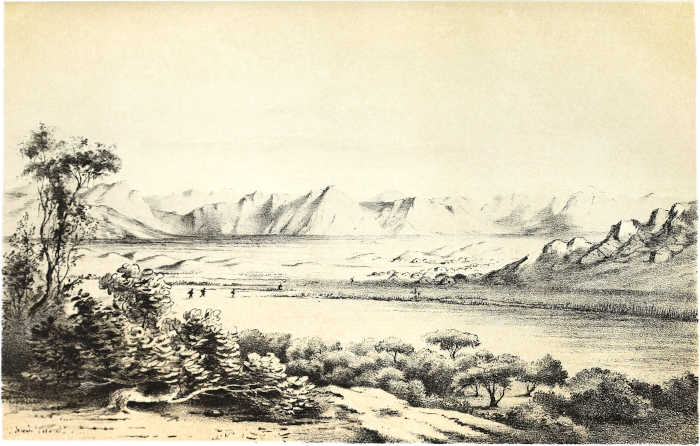

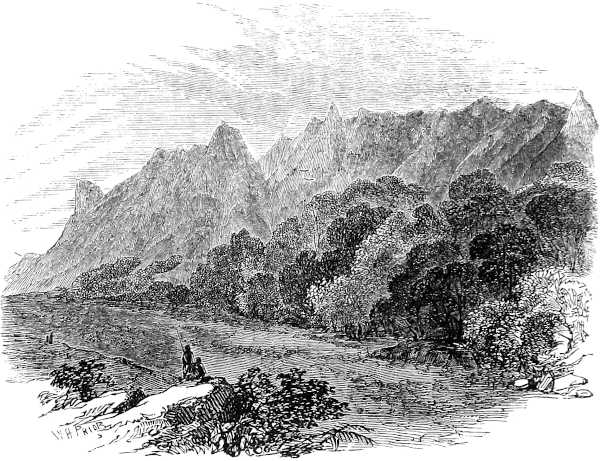

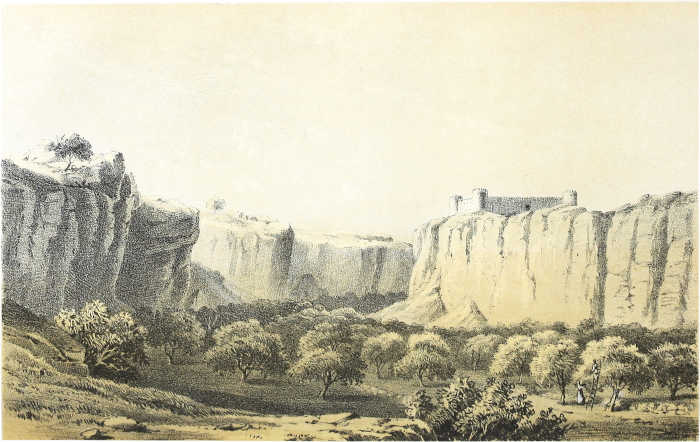

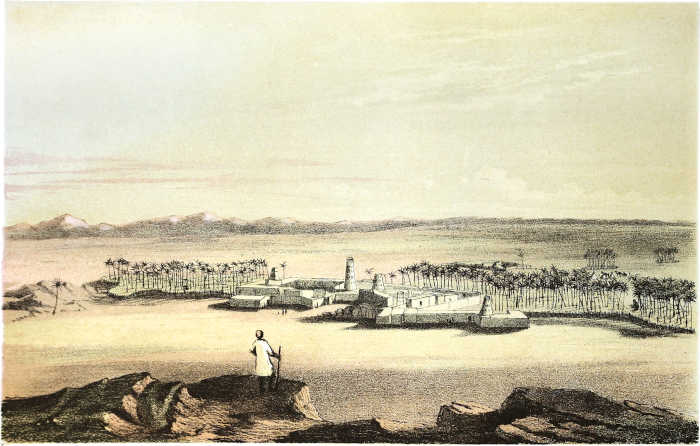

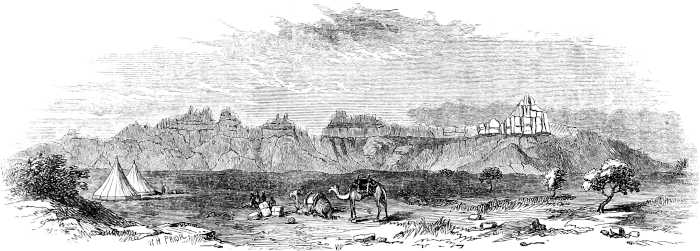

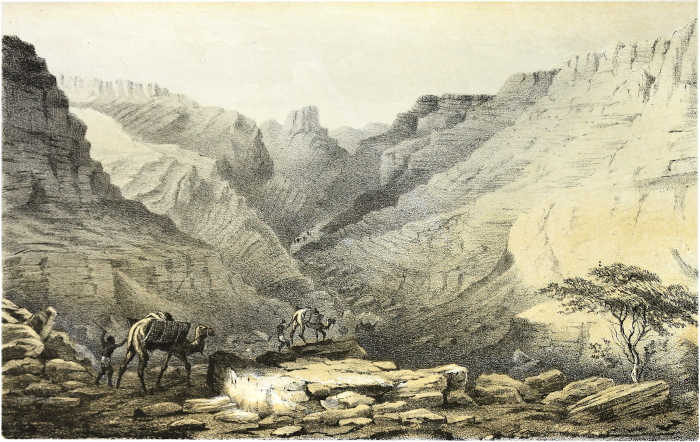

| 1. | Aúderas | Frontispiece | |

| 2. | Wádí Welád ʿAlí | to face | 29 |

| 3. | Kasr Ghurián and W. Rummána | „ | 49 |

| 4. | Mizda | „ | 100 |

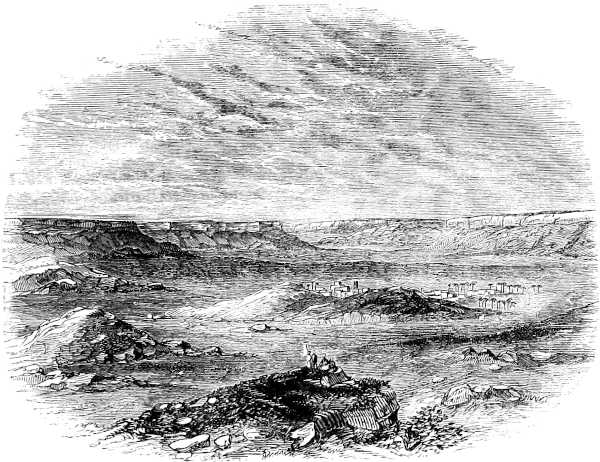

| 5. | El Hasi | „ | 141 |

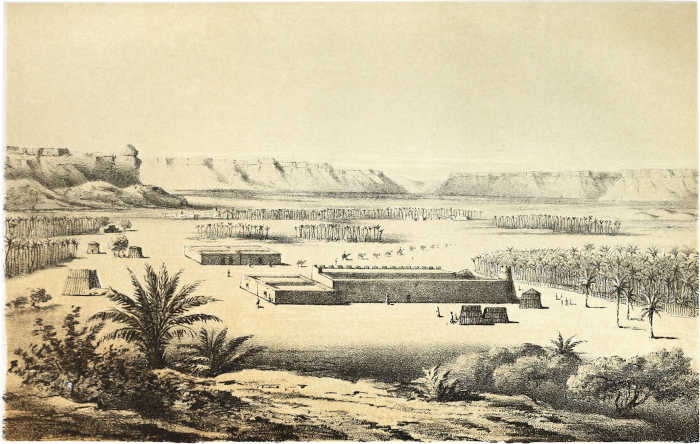

| 6. | Éderi | „ | 146 |

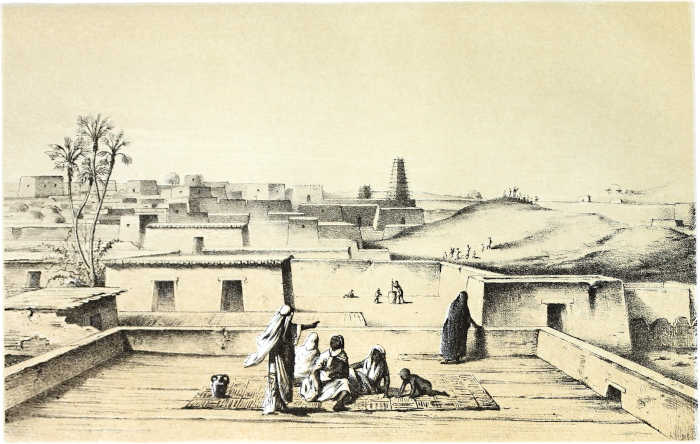

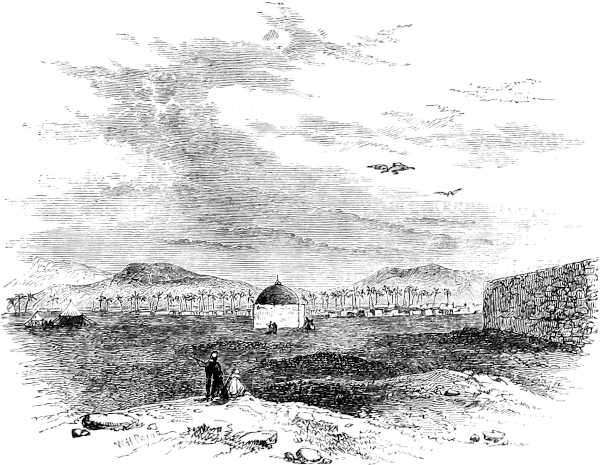

| 7. | Múrzuk | „ | 168 |

| 8. | Telísaghé | „ | 196 |

| 9. | Ghát | „ | 238 |

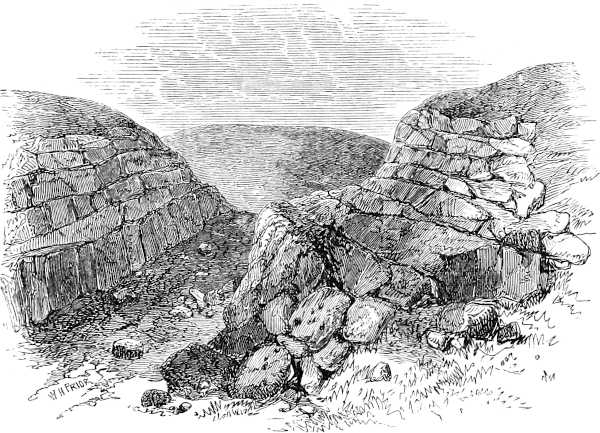

| 10. | Égeri | „ | 252 |

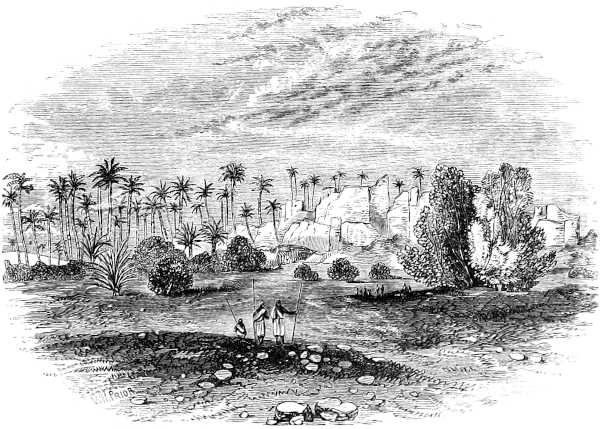

| 11. | Tintéllust | „ | 334 |

| 12. | Ágades | „ | 408 |

| [xxxv]WOODCUTS. | |||

| Picturesque Fountain | 27 | ||

| General View of Enshéd e’ Sufét | 34 | ||

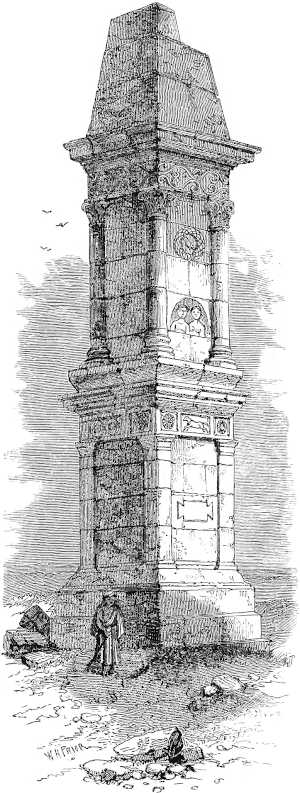

| The Monument | 35 | ||

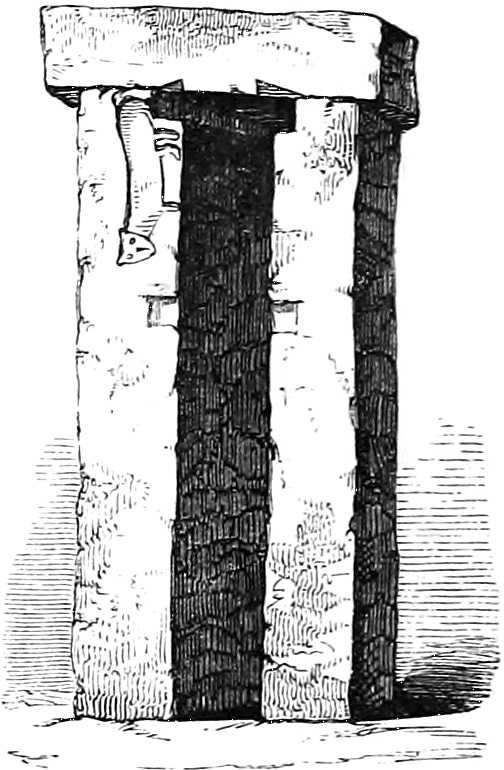

| Aboriginal Structures | 58 | ||

| Kasr Dóga | 70 | ||

| Another pair of Pillars, with Slab and Sculpture of a Dog | 74 | ||

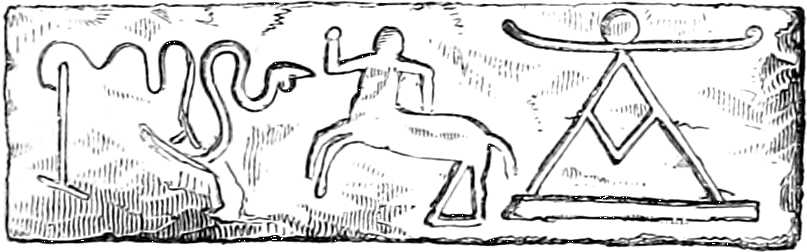

| Curious Sculpture | 79 | ||

| General View of Mizda | 101 | ||

| Kasr Khafaije ʿAámer | 106 | ||

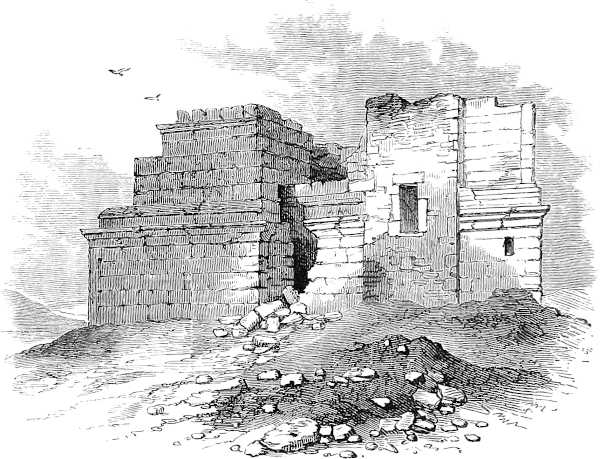

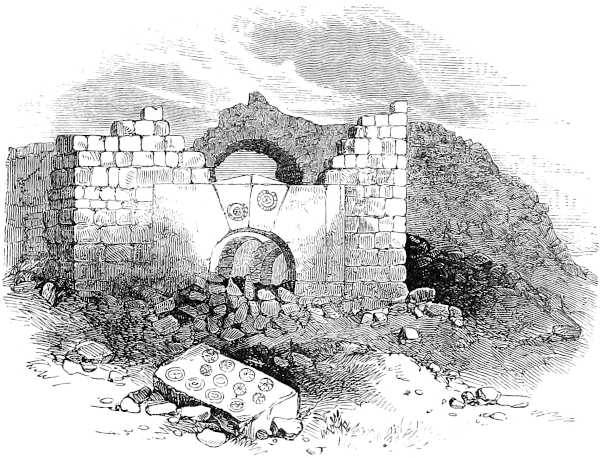

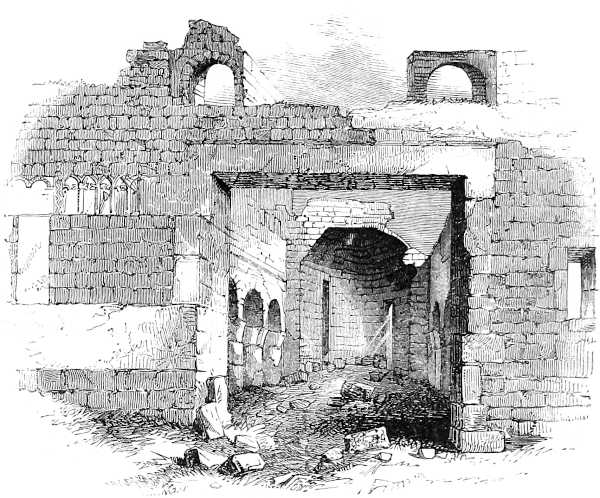

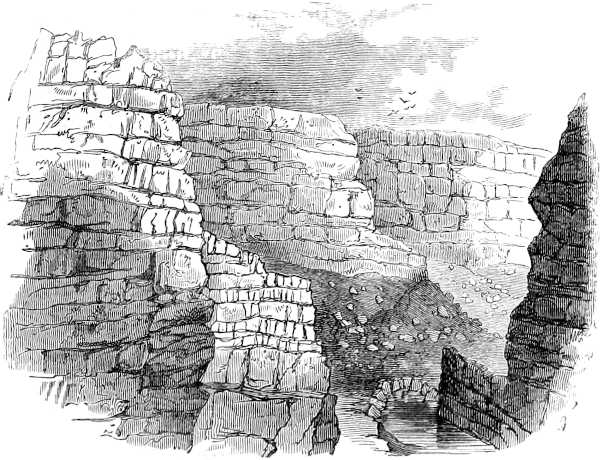

| Ruins of Christian Church | 108 | ||

| Two Capitals | 109 | ||

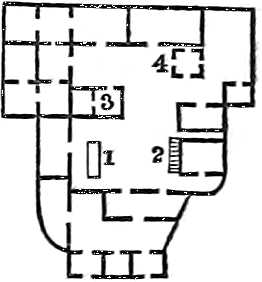

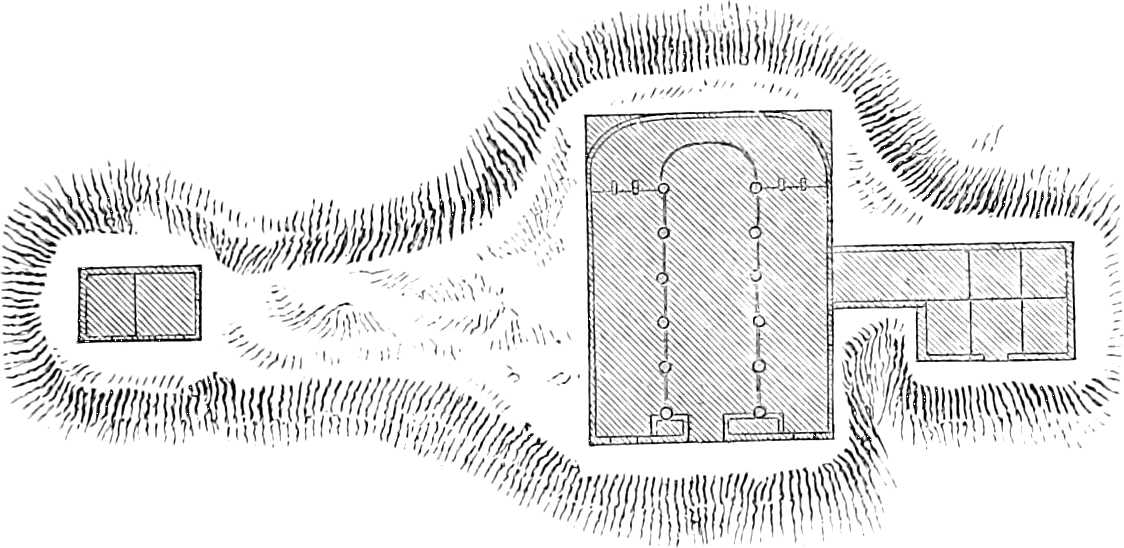

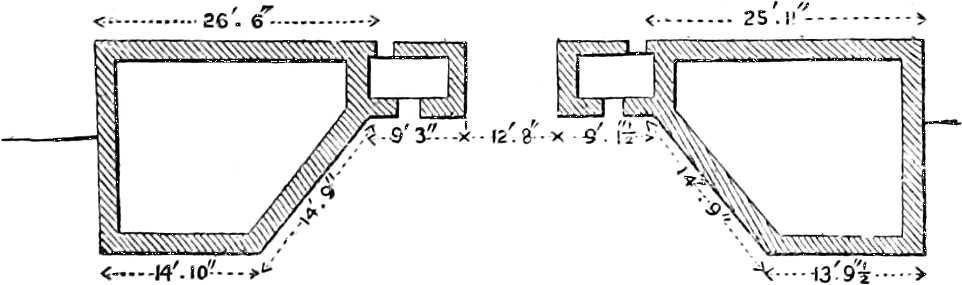

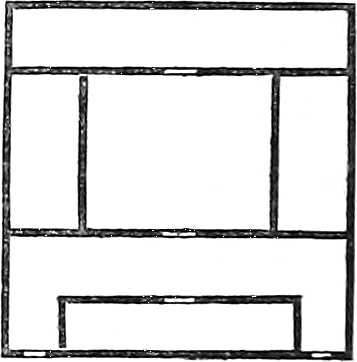

| Ground-plan | 111 | ||

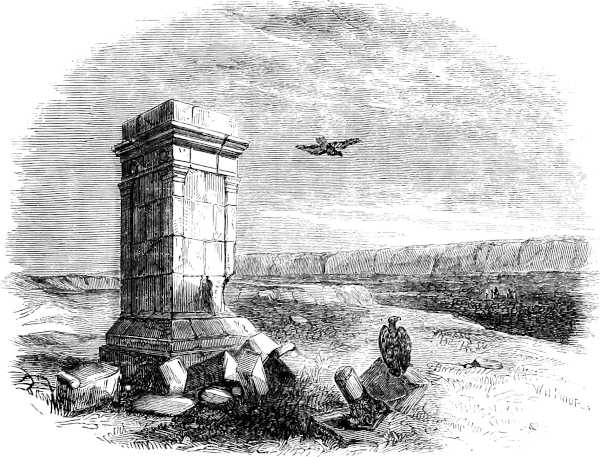

| Roman Sepulchre in Wádí Talha | 113 | ||

| Roman Sepulchre in Wádí Tagíje | 117 | ||

| Roman Sepulchre at Taboníye | 124 | ||

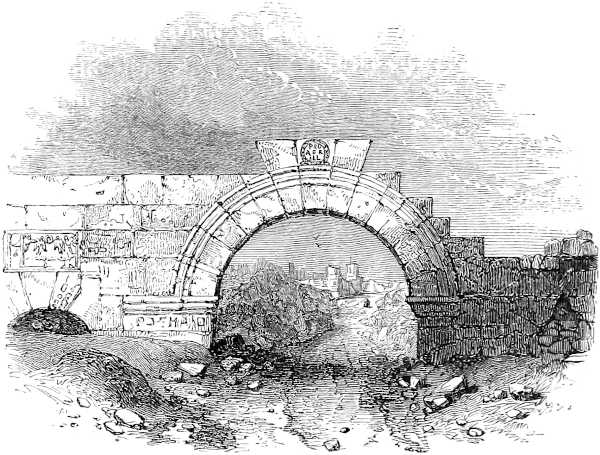

| Gateway of Roman Station at Gharíya | 126 | ||

| Ground-plan of Station | 129 | ||

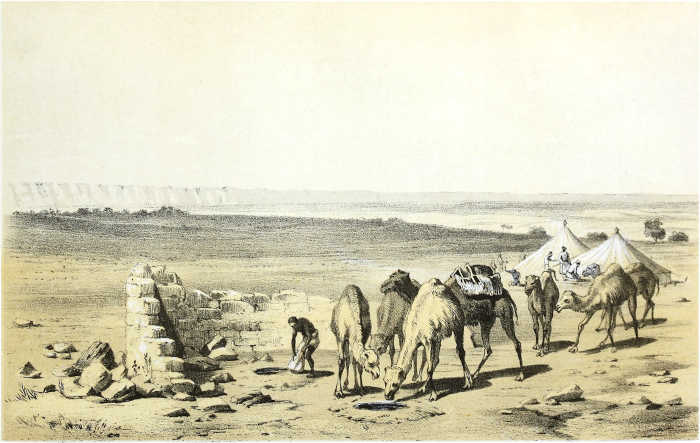

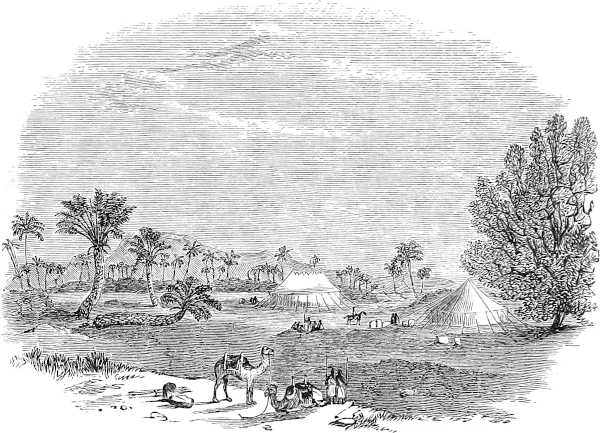

| Encampment at Ugréfe | 154 | ||

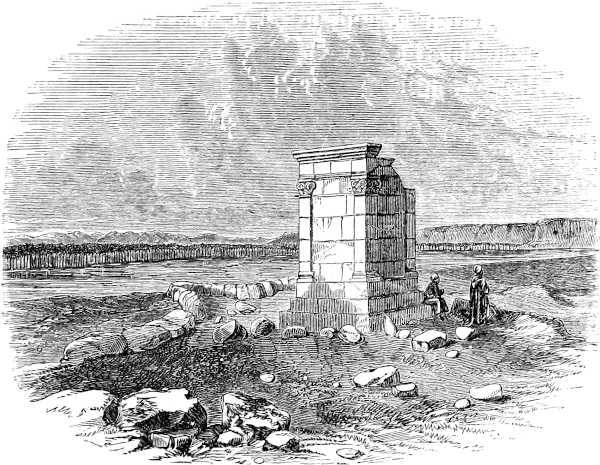

| Roman Sepulchre near Jerma (Garama) | 157 | ||

| Ground-plan of Múrzuk | 169 | ||

| Tiggerurtín | 173 | ||

| Encampment at Tesémmak | 189 | ||

| Hatíta on his Camel | 195 | ||

| First Sculpture of Telisaghé (two deities) | 197 | ||

| Herd of Bulls | 200 | ||

| Bull jumping into a Ring | 201 | ||

| Mount Ídinen | 213 | ||

| Ground-plan of Quarters at Ghát | 222 | ||

| The Mountain Pass | 251 | ||

| Pond in Valley Égeri | 253 | ||

| Mount Tiska | 258 | ||

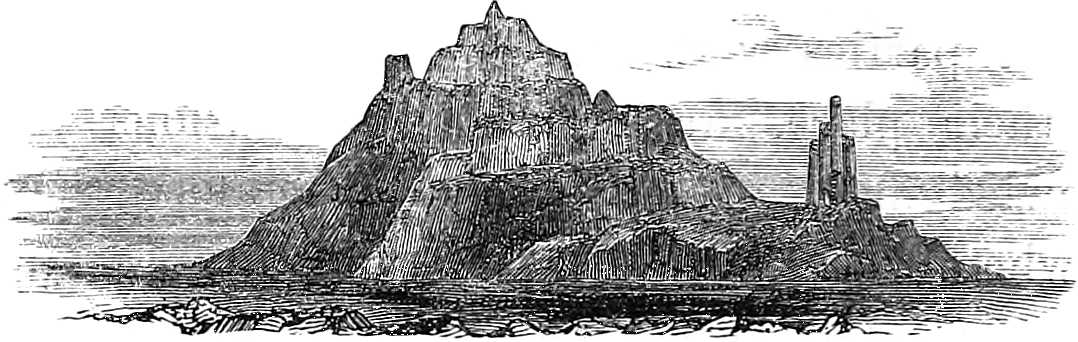

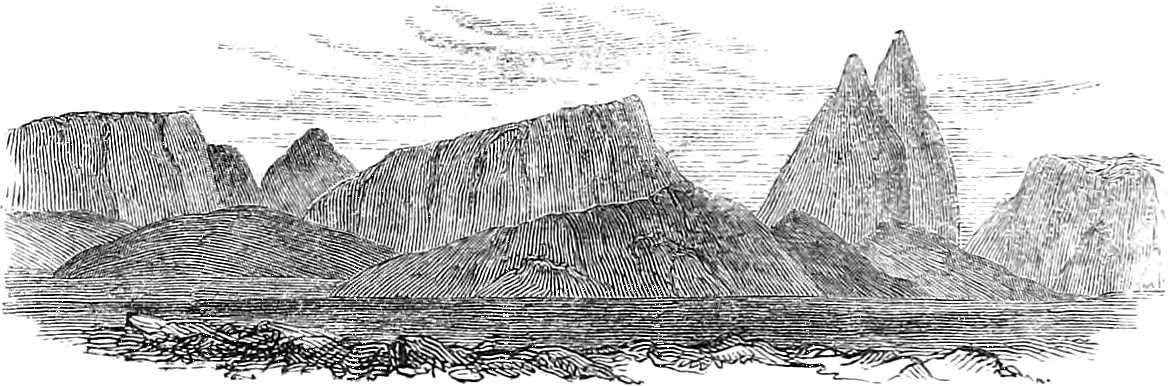

| Picturesque Peak | 267 | ||

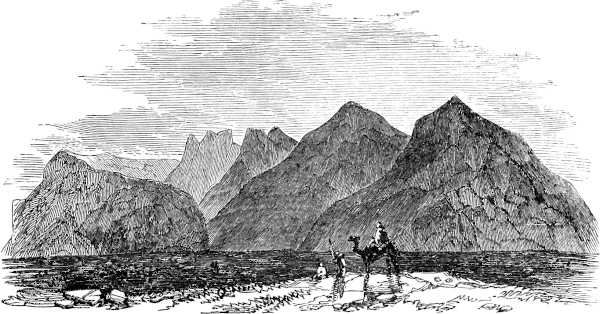

| Mountain-ridge near Arókam | 269 | ||

| Indented Ridge | 270 | ||

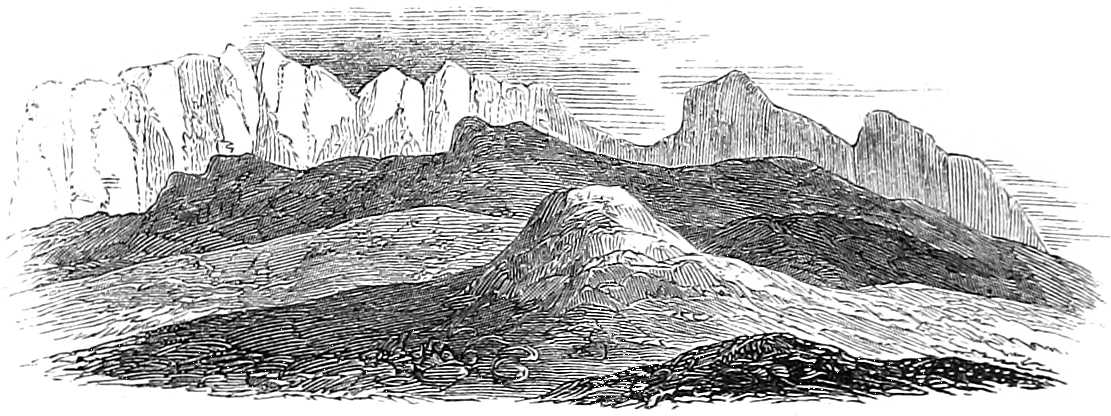

| Stratified Mount | 276 | ||

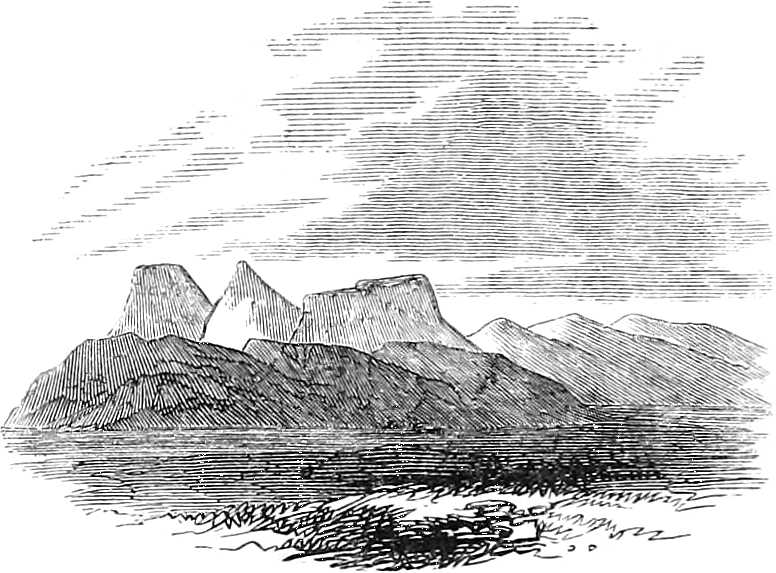

| Mountain-group | 292 | ||

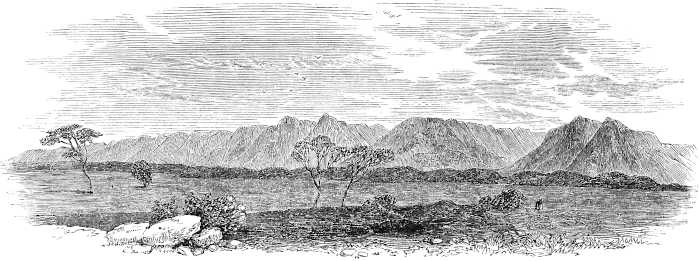

| [xxxvi]View of Mountain-chains | 294 | ||

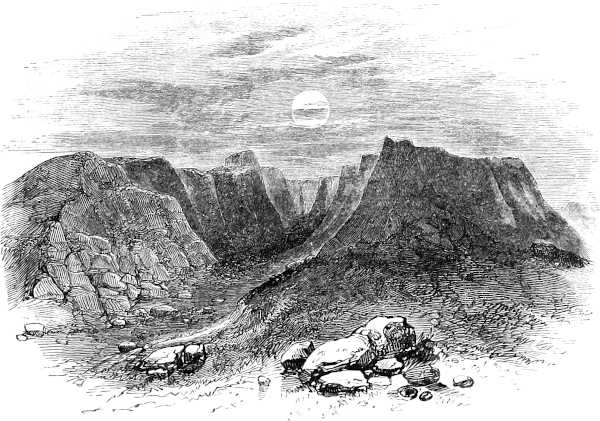

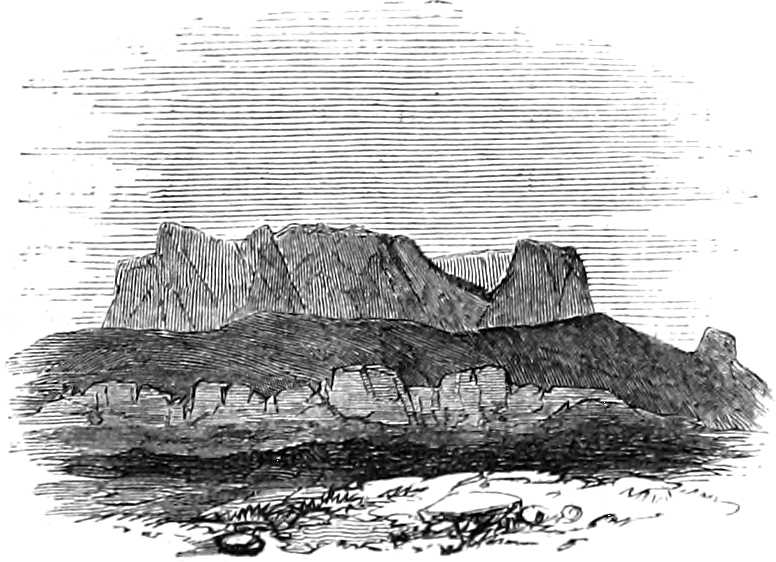

| Mountains of Tídik | 311 | ||

| Mount Kadamméllet | 312 | ||

| Mountains of Selúfiet | 320 | ||

| Valley of Fódet | 329 | ||

| Mount Cheréka and Eghellál | 374 | ||

| Mount Cheréka, from another side | 375 | ||

| Mountain-chain | 377 | ||

| Deep Chasm of Mount Eghellál | 378 | ||

| Mount Ágata | 379 | ||

| Mount Belásega | 380 | ||

| Valley Tíggeda | 382 | ||

| Distinguished Mount | 388 | ||

| Audience-hall of Chief of Ágades | 400 | ||

| Mohammed Bóro’s House | 403 | ||

| A Leather Box | 406 | ||

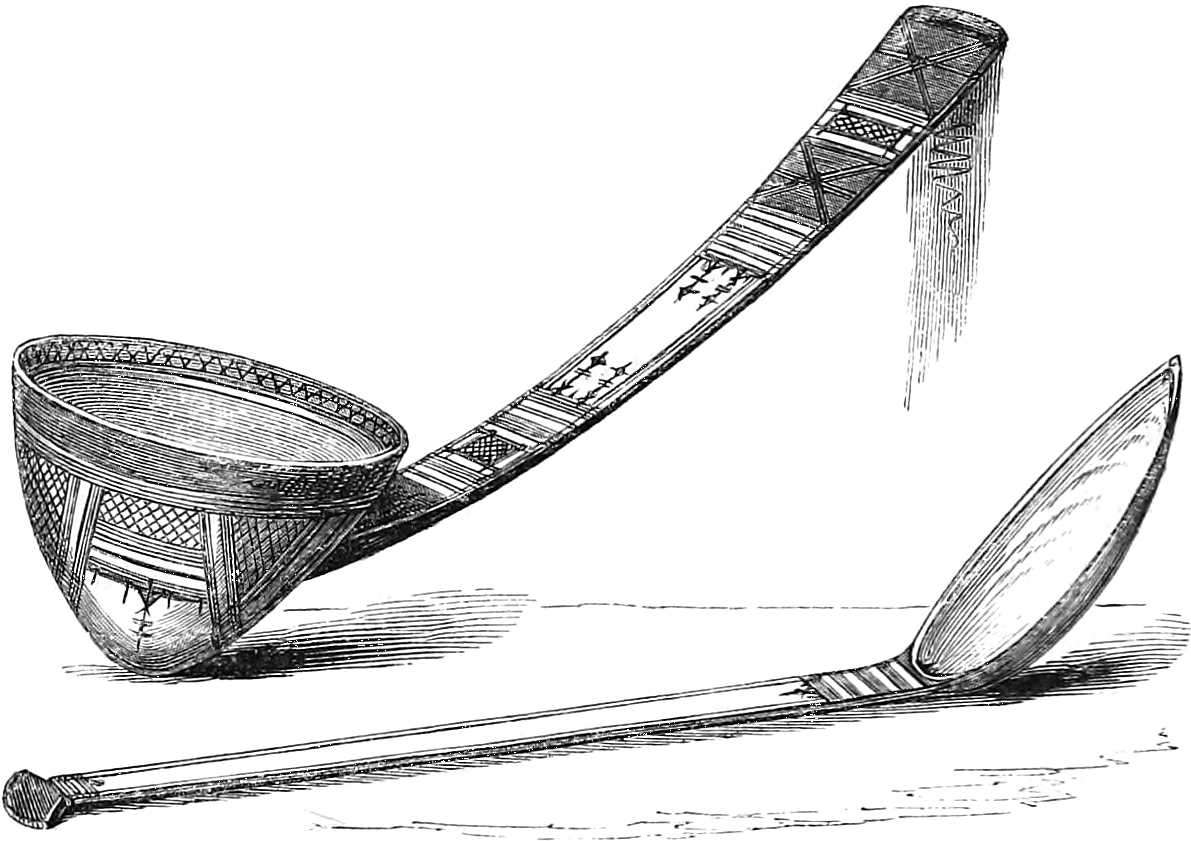

| Two Native Spoons | 414 | ||

| Ground-plan of a House | 442 | ||

| Another Ground-plan | 446 | ||

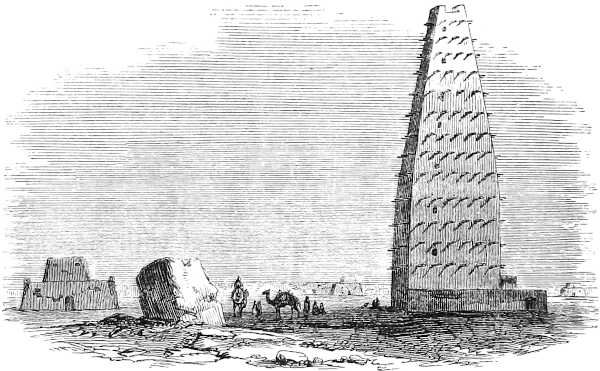

| View of the High Watch-tower | 450 | ||

| Ground-plan of Ágades | 475 | ||

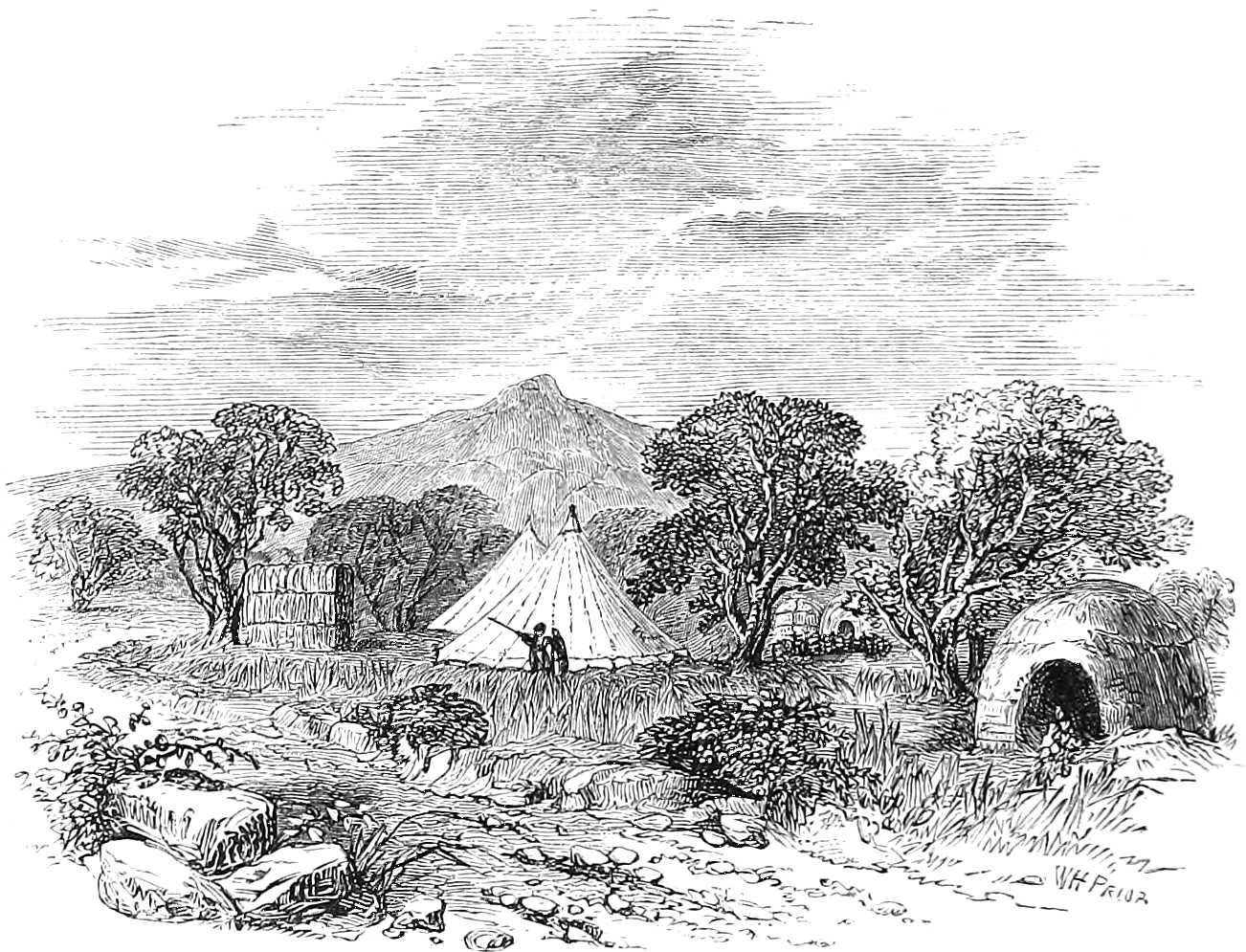

| Encampment in Tin-téggana | 488 | ||

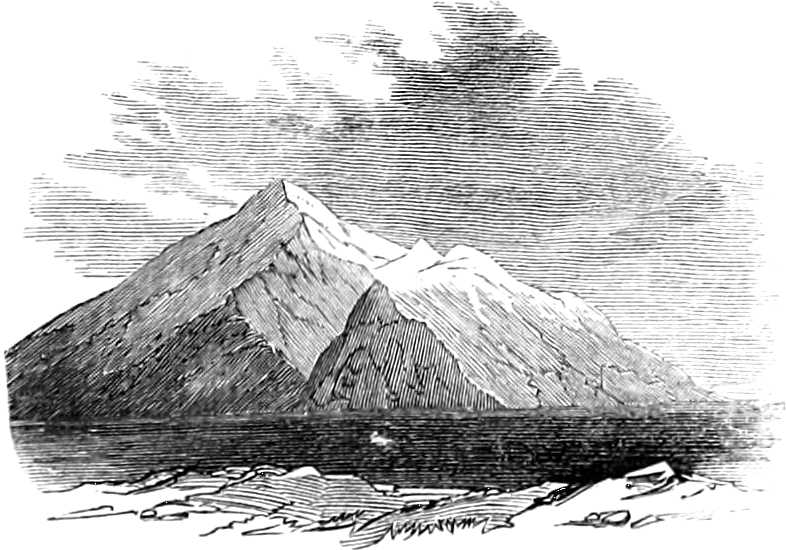

| Mount Mári, in profile | 506 | ||

| Mount Mári, in front | 507 | ||

| Mount Bághzen, from the east side | 512 | ||

[1]TRAVELS AND

DISCOVERIES

IN

AFRICA.

CHAPTER I.

FROM TUNIS TO TRIPOLI.

Mr. Richardson was waiting in Paris for despatches, when Mr. Overweg and I reached Tunis, by way of Philippeville and Bona, on the 15th of December, 1849; and having, through the kind interference of Mr. Ferrier the British vice-consul, been allowed to enter the town after six days’ quarantine, we began immediately to provide ourselves with articles of dress, while in the meantime we took most interesting daily rides to the site of ancient Carthage.

Having procured many useful articles for our journey, and having found a servant, the son of a freed slave from Gober, we left Tunis on the 30th of December[6], and passed the first night in Hammám el[2] Enf. Early next morning we followed the charming route by Krumbália, which presents a no less vivid specimen of the beauty and natural fertility of the Tunisian country than of the desolate state to which it is at present reduced. We then passed the fine gardens of Turki, a narrow spot of cultivation in a wide desolate plain of the finest soil; and leaving el Khwín to our right, we reached el Arbʿain.

Both these places enjoy a peculiar celebrity with the natives. El Khwín is said to have been once a populous place; but nearly all its inhabitants were destroyed by a spring of bituminous water, which according to tradition, afterwards disappeared. El Arbʿain, the locality of the “forty” martyrs, is a holy place; and ʿAli, our muleteer, in his pious zeal, took up a handful of the sacred earth and sprinkled it over us. It is a most picturesque spot. Keeping then along the wild plain covered with a thick underwood of myrtle, we beheld in the distance the highly picturesque and beautiful Mount Zaghwán, the Holy Mountain of the ancient inhabitants, which rose in a majestic form; and we at length reached Bir el buwíta, “the well of the little closet,” at one o’clock in the afternoon. The “little closet,” however, had given place to a most decent-looking whitewashed khán, where we took up our quarters in a clean room. But our buoyant spirits did not allow us long repose; and a quarter before eleven at night we were again on our mules.

I shall never forget this, the last night of the year[3] 1849, which opened to us a new era with many ordeals, and by our endurance of which we were to render ourselves worthy of success. There were, besides ourselves, our servants, and our two muleteers, four horsemen of the Bey, and three natives from Jirbi. When midnight came my fellow traveller and I saluted the new year with enthusiasm, and with a cordial shake of the hand wished each other joy. Our Mohammedan companions were greatly pleased when they were informed of the reason of our congratulating each other, and wished us all possible success for the new year. We had also reason to be pleased with them; for by their not inharmonious songs they relieved the fatigue of a long, sleepless, and excessively cold night.

Having made a short halt under the olive-trees at the side of the dilapidated town of Herkla, and taken a morsel of bread, we moved on with our poor animals without interruption till half an hour after noon, when we reached the funduk (or caravanserai) Sidi Bú Jʿafer, near Súsa, where we took up our quarters, in order to be able to start again at night, the gates of the town being kept shut till morning.[7]

Starting before three o’clock in the morning, we were exactly twelve hours in reaching El Jem, with the famous Castle of the Prophetess, still one of the[4] most splendid monuments of Roman greatness overhanging the most shabby hovels of Mohammedan indifference. On the way we had a fine view, towards the west, of the picturesque Jebel Trutsa, along the foot of which I had passed on my former wanderings, and of the wide, out-stretching Jebel Useleet.

Another ride of twelve hours brought us, on the 3rd of January 1850, to Sfákes, where we were obliged to take up our quarters in the town, as our land-journey was here at an end, and we were to procure a vessel to carry us either direct to Tripoli, or to some other point on the opposite side of the Lesser Syrtis. The journey by land is not only expensive, particularly for people who are encumbered with a good deal of luggage, as we then were, and very long and tedious, but is also very unsafe, as I found from experience on my former journey. The island of Jirbi, which forms the natural station of the maritime intercourse between the regency of Tunis and that of Tripoli, had been put under the strictest rules of quarantine, rather from political considerations than from those of health, all intercourse with the mainland having been cut off. It was therefore with great difficulty that we succeeded in hiring a “gáreb” to carry us to Zwára, in which we embarked in the forenoon of Saturday the 5th of January.

During our two days’ stay in Sfákes we made the acquaintance of a Jew calling himself Baránes, but who is in truth the Jew servant named Jacob who accompanied Denham and Clapperton, and is several[5] times mentioned in the narrative of those enterprising travellers as self-conceited and stubborn; yet he seems to be rather a clever fellow, and in some way or other contrives to be on the best terms with the governor. He communicated to us many anecdotes of the former expedition, and, among other things, a very mysterious history of a Danish traveller in disguise whom they met in Borno coming all the way from Dar-Fúr through Wadaï. There is not the least mention of such a meeting in the journal of the expedition, nor has such an achievement of a European traveller ever been heard of; and I can scarcely believe the truth of this story, though the Jew was quite positive about it.

The vessel in which we embarked was as miserable as it could be, there being only a small low cabin as high as a dog-kennel, and measuring, in its greatest width, from six to seven feet, where I and my companion were to pass the night. We thought that a run of forty-eight hours, at the utmost, would carry us across the gulf; but the winds in the Lesser Syrtis are extremely uncertain, and sometimes so violent that a little vessel is obliged to run along the coast.

At first we went on tolerably well; but the wind soon became unfavourable, and in the evening we were obliged to cast anchor opposite Nekta, and, to our despair, were kept there till the afternoon of Tuesday, when at length we were enabled to go forward in our frail little shell, and reached Méheres[6]—not Sidi Méheres, as it is generally called in the maps—in the darkness of night. Having made up our minds rather to risk anything than to be longer immured in such a desperate dungeon as our gáreb, we went on shore early on Wednesday morning with all our things, but were not able to conclude a bargain with some Bedowín of the tribe of the Léffet, who were watering their camels at the well.

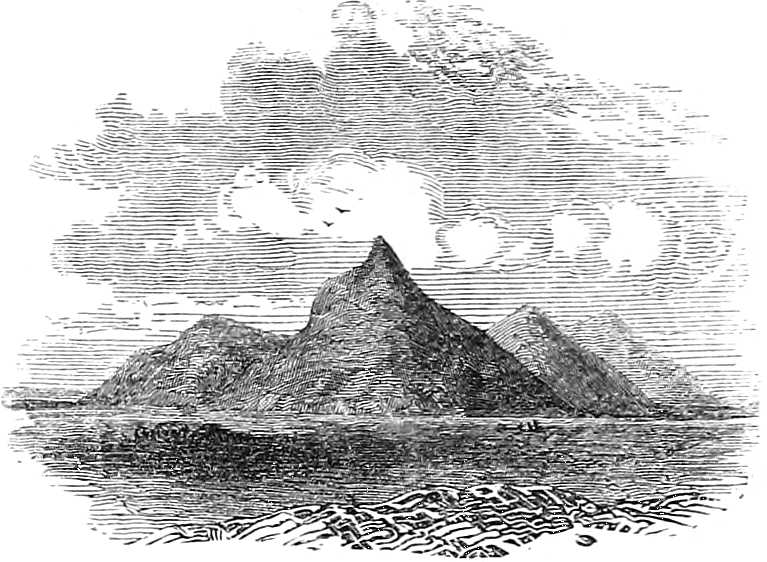

The majestic ruins of a large castle, fortified at each corner with a round tower, give the place a picturesque appearance from the seaside. This castle is well known to be a structure of the time of Ibrahim the Aghlabite. In the midst of the ruins is a small mosque. But notwithstanding the ruinous state of the place, and the desolate condition of its plantations, there is still a little industry going on, consoling to the beholder in the midst of the devastation to which the fine province of Byzacium, once the garden of Carthage, is at present reduced. Several people were busily employed in the little market-place making mats; and in the houses looms, weaving baracans, were seen in activity. But all around, the country presented a frightful scene of desolation, there being no object to divert the eye but the two apparently separate cones of Mount Wuedrán, far in the distance to the west, said to be very rich in sheep. The officer who is stationed here, and who showed us much kindness, furnishing us with some excellent red radishes of extraordinary size, the only luxury which the village affords, told us that not less than five hundred soldiers are quartered upon this part[7] of the coast. On my former journey I had ample opportunity to observe how the Tunisian soldiery eat up the little which has been left to the peaceable inhabitants of this most beautiful, but most unfortunate country.

Having spent two days and two nights in this miserable place without being able to obtain camels, we resolved to try the sea once more, in the morning of the 11th, when the wind became northerly; but before the low-water allowed us to go on board, the wind again changed, so that, when we at length got under weigh in the afternoon, we could only move on with short tacks. But our captain, protected as he was by the Promontory of Méheres, dared to enter the open gulf. Quantities of large fish in a dying state, as is often the case in this shallow water when the wind has been high, were drifting round our boat.

The sun was setting when we at length doubled the promontory of Kasr Unga, which we had already clearly distinguished on the 8th. However, we had now overcome the worst; and when on the following morning I emerged from our suffocating berth, I saw, to my great delight, that we were in the midst of the gulf, having left the coast far behind us. I now heard from our raïs that, instead of coasting as far as Tarf el má (“the border of the water”), a famous locality in the innermost corner of the Lesser Syrtis, which seems to preserve the memory of the former connection between the gulf and the great Sebkha or Shot el Kebír (the “palus Tritonis”), he had[8] been so bold as to keep his little bark straight upon the channel of Jirbi.

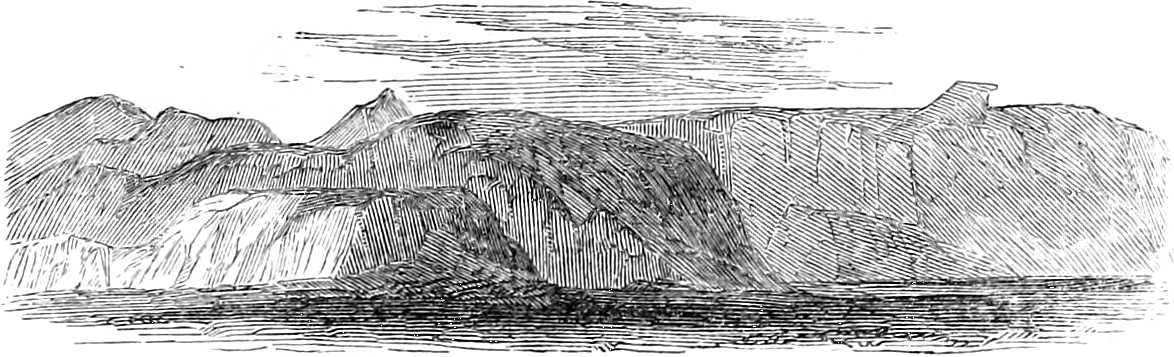

Our voyage now became interesting; for while we were advancing at a fair rate, we had a charming view of the mountain-range, which in clear contours extended along in the distance behind the date-groves on the coast, seen only in faint outlines. The western part of the chain is very low, and forms almost a group apart, but after having been intersected by a gap or “gate,” the chain rises to greater elevation, being divided, as it would seem from hence, into three separate ranges enclosing fine valleys.

We had hoped to cross the difficult channel to-day; but the wind failing, we were obliged to anchor and await the daylight, for it is not possible to traverse the straits in the night, on account of their extreme shallowness. Even in the light of the following day, when we at length succeeded, our little bark, which drew only two or three feet, struck twice, and we had some trouble to get afloat again. On the conspicuous and elevated promontory the “Jurf,” or “Tarf el jurf,” stood in ancient times a temple of Venus, the hospitable goddess of the navigator. Here on my former journey I crossed with my horses over from the main to the island of Jirbi, while from the water I had now a better opportunity of observing the picturesque character of the rugged promontory. After traversing the shallow basin or widening, we crossed the second narrowing, where the castles which defended the bridge or “kantara,” the “pons Zitha” of[9] the Romans, now lie in ruins on the main as well as on the island, and greatly obstruct the passage, the difficulty of which has obtained celebrity from contests between Islam and Christianity in comparatively modern times.

Having passed safely through this difficult channel, we kept steadily on through the open sea; and doubling Rás Mʿamúra, near to which our captain had a little date-grove and was cheerfully saluted by his family and friends, we at length entered the harbour of Zarzís, late in the afternoon of Sunday, and with some trouble got all our luggage carried into the village, which is situated at some distance. For although we had the worst part of the land journey now before us, the border-district of the two regencies, with the unsafe state of which I was well acquainted from my former journey, and although we were insufficiently armed, we were disposed to endure anything rather than the imprisonment to which we were doomed in such a vessel as our Mohammed’s gáreb. I think, however, that this nine days’ sail between Sfákes and Zarzís, a distance of less than a hundred and twenty miles, was on the whole a very fair trial in the beginning of an undertaking the success of which was mainly dependent upon patience and resolute endurance. We were rather fortunate in not only soon obtaining tolerable quarters, but also in arranging without delay our departure for the following day, by hiring two horses and three camels.

[10]Zarzís consists of five separate villages—Kasr Bú ʿAli, Kasr Mwanza, Kasr Welád Mohammed, Kasr Welád Sʿaid, and Kasr Zawíya; the Bedowín in the neighbourhood belong to the tribe of the Akára. The plantation also is formed into separate date-groves. The houses are in tolerable repair and neatly whitewashed; but the character of order and well-being is neutralized by a good many houses in decay. Near the place there are also some Roman ruins, especially a cistern of very great length; and at some distance is the site of Medinet Ziyán, of which I have given a description in the narrative of my former journey.

Besides the eight men attached to our five animals, we were joined here by four pilgrims and three Tripolitan traders; we thus made up a numerous body, armed with eight muskets, three blunderbusses, and fourteen pistols, besides several straight swords, and could venture upon the rather unsafe road to the south of the Lake of Bibán, though it would have been far more agreeable to have a few trustworthy people to rely on instead of these turbulent companions.

Entering soon, behind the plantation of Zarzís, a long narrow sebkha, we were struck by the sterile and desolate character of the country, which was only interrupted by a few small depressed localities, where a little corn was cultivated. Keeping along this tract of country, we reached the north-western corner of the Lake of Bibán, or Bahéret el Bibán, after a little more than eight miles. This corner has even at[11] the present day the common name of Khashm el kelb (the Dog’s Nose), while the former classical name of the whole lake, Sebákh el keláb, was only known to Tayyef, the more learned of my guides, who, without being questioned by me, observed that in former times towns and rich corn-fields had been where the lake now is, but had been swallowed up by a sinking of the ground.

The real basin has certainly nothing in common with a sebkha, which means a shallow hollow, incrusted with salt, which at times is dry and at others forms a pool; for it is a deep gulf or fiord of the sea, with which it is connected only by a narrow channel called Wád mtʿa el Bibán. The nature of a sebkha belongs at present only to its shores, chiefly to the locality called Makháda, which, indenting the country to a great distance, is sometimes very difficult to pass, and must be turned by a wide circuitous path, which is greatly feared on account of the neighbourhood of the Udérna, a tribe famous for its highway robberies. Having traversed the Makháda (which at present was dry) without any difficulty, we entered upon good arable soil, and encamped, after sunset, at about half a mile distance from a Bedowín encampment.

January 15th.Starting from here the following day, we soon became aware that the country was not so thinly inhabited as we had thought; for numerous herds covered the rich pasture-grounds, while droves of gazelles, now and then, attested that the industry[12] of man did not encroach here upon the freedom of the various orders of creation. Leaving the path near the ruins of a small building situated upon a hill, I went with Tayyef and the Khalífa to visit the ruins of a Roman station on the border of the Bahéra, which, under the name of el Medaina, has a great fame amongst the neighbouring tribes, but which, with a single exception, are of small extent and bad workmanship. This exception is the quay, which is not only of interest in itself, formed as it is of regularly-hewn stones, in good repair, but of importance as an evident proof that the lake was much deeper in ancient times than it is now.

Traversing from this spot the sebkha, which our companions had gone round, we soon overtook them, and kept over fine pasture-grounds called el Fehén, and further on, Súllub, passing, a little after noon, a group of ruins near the shore, called Kitfi el hamár. At two o’clock in the afternoon, we had directly on our right a slight slope which, according to the unanimous statement of our guides and companions, forms the mágttʿa, مَقْطَعٌ, or frontier between the two regencies[8]; and keeping along it we encamped an hour afterwards between the slope and the shore, which a little further on forms the deep gulf called Mirsá Buréka.

[13]January 16th.Starting at an early hour, we reached after a march of ten miles the ruins of a castle on the sea-shore, called Búrj el Melha, to which those of a small village, likewise built of hewn stone, are joined, while a long and imposing mole called el Míná juts out into the gulf. Four and a half miles further on we reached the conspicuous hill on the top of which is the chapel of the saint Sidi Sʿaid ben Salah, sometimes called Sidi Gházi, and venerated by such of the natives as are not attached to the Puritan sect of El Mádani, of which I shall speak hereafter. All our companions went there to say a short prayer.

Here we left the shore, and, having watered our animals near a well and passed the chapel of Sidi Sʿaid, close to which there are some ruins, we passed with expedition over fine meadows till we approached the plantation of Zowára, when, leaving Mr. Overweg and my people behind, I rode on with the Khalífa, in order to procure quarters from my former friend Sʿaid bu Semmín, who, as I had heard to my great satisfaction, had been restored to the government of that place. He had just on that very day returned from a visit of some length in the capital, and was delighted to see me again; but he was rather astonished when he heard that I was about to undertake a far more difficult and dangerous journey than my former one along the coast, in which he well knew that I had had a very narrow escape. However, he confided in my enterprising spirit and in the mercy of the Almighty, and[14] thought if anybody was likely to do it, I was the man.[9]

January 17th.We had now behind us the most dreary part of our route, having entered a district which in ancient times numbered large and wealthy cities, among which Sabratha stands foremost, and which even in the present miserable state of the country is dotted with pleasant little date-groves, interrupted by fine pasture-grounds. In the westernmost part of this tract, however, with the exception of the plantation of Zowára, all the date-groves, as those of Rikdalíye, Jemíl, el Meshíah, and Jenán ben Síl, lie at a considerable distance from the coast, while the country near the sea is full of sebkhas, and very monotonous, till the traveller reaches a slight ridge of sand-hills about sixteen miles east from Zowára, which is the border between the dreary province of that government and a more favoured tract belonging to the government of Bú-ʿAjíla, and which lies a little distance inland. Most charming was the little plantation of Kasr ʿalaiga, which exhibited traces of industry and improvement. Unfortunately our horses were too weak and too much fatigued to allow us to visit the sites either of Sabratha or Pontes. The ruins of Sabratha are properly[15] called Kasr ʿalaiga, but the name has been applied to the whole neighbourhood; to the ancient Pontes seem to belong the ruins of Zowára e’ sherkíyeh, which are considerable. Between them lies the pretty grove of Om el hallúf.

About four o’clock in the afternoon we traversed the charming little valley called Wadi bú-harída, where we watered our horses; and then following the camels, and passing Asermán with its little plantation, which is bordered by a long and deep sebkha, we took up our quarters for the night in an Arab encampment, which was situated in the midst of the date-grove of ʿUkbah, and presented a most picturesque appearance, the large fires throwing a magic light upon the date-trees. But there are no roses without thorns: we were unfortunately persuaded to make ourselves comfortable in an Arab tent, as we had no tent of our own; and the enormous swarms of fleas not only disturbed our night’s rest, but followed us to Tripoli.

We had a long stretch the following day to reach the capital, which we were most anxious to accomplish, as we expected Mr. Richardson would have arrived before us in consequence of our own tedious journey; and having sent the Khalífa in advance to keep the gate open for us, we succeeded in reaching the town after an uninterrupted march of thirteen hours and a half, and were most kindly received by Mr. Crowe, Her Majesty’s consul-general, and the vice-consul Mr. Reade, with whom I was already[16] acquainted. We were surprised to find that Mr. Richardson had not even yet been heard of, as we expected he would come direct by way of Malta. But he did not arrive till twelve days after. With the assistance of Mr. Reade, we had already finished a great deal of our preparations, and would have gladly gone on at once; but neither the boat, nor the instruments, nor the arms or tents had as yet arrived, and a great deal of patience was required. However, being lodged in the neat house of the former Austrian consul, close to the harbour, and which commands a charming prospect, our time passed rapidly by.

On the 25th of January Mr. Reade presented Mr. Overweg and me to Yezíd Bashá, the present governor, who received us with great kindness and good feeling. On the 29th we had a pleasant meeting with Mr. Frederic Warrington on his return from Ghadámes, whither he had accompanied Mr. Charles Dickson, who on the 1st of January had made his entry into that place as the first European agent and resident. Mr. F. Warrington is perhaps the most amiable possible specimen of an Arabianized European. To this gentleman, whose zeal in the objects of the expedition was beyond all praise, I must be allowed to pay my tribute as a friend. On setting out in 1850, he accompanied me as far as the Ghurián; and on my joyful return in 1855 he received me in Murzuk. By the charm of friendship he certainly contributed his share to my success.

[6]I cannot leave Tunis without mentioning the great interest taken in our undertaking, and the kindness shown to us, by M. le Baron Théis, the French consul.

[7]The town presented quite the same desolate character which I have described in my former journey, with the single exception that a new gate had since been built. Several statues had been brought from Medinet Ziyán.

[8]This point is not without importance, as a great deal of dispute has taken place about the frontier. Having on my former journey kept close along the seashore, I have laid it down erroneously in the map accompanying the narrative of that journey.

[9]I will here correct the mistake which I made in my former narrative, when I said that Zowára is not mentioned by Arabic authors. It is certainly not adverted to by the more celebrated and older writers; but it is mentioned by travellers of the 14th century, especially by the Sheikh e’ Tijáni.

DR. BARTH’S TRAVELS

IN NORTH AND CENTRAL AFRICA

Sheet No. 2.

MAP OF THE ROUTE

through the

YÉFREN, GHURIÁN, TARHÓNA & MESELLÁTA MTS.

4 to 26 February

1850.

Constructed and drawn by A. Petermann.

Engraved by E. Weller, Duke Strt. Bloomsbury.

London, Longman & Co.

[17]CHAP. II.

TRIPOLI. — THE PLAIN AND THE MOUNTAIN-SLOPE; THE ARAB AND THE BERBER.

In the Introduction I have given a rapid sketch of our journey from Tunis, and pointed out the causes of our delay in Tripoli. As soon as it became apparent that the preparations for our final departure for the interior would require at least a month, Mr. Overweg and I resolved to employ the interval in making a preliminary excursion through the mountainous region that encompasses Tripoli in a radius of from sixty to eighty miles.

With this view, we hired two camels, with a driver each, and four donkeys, with a couple of men, for ourselves and our two servants, Mohammed Belāl, the son of a liberated Háusa slave, and Ibrahim, a liberated Bagirmi slave, whom we had been fortunate enough to engage here; and through the Consul’s influence we procured a shoush, or officer, to accompany us the whole way.

Neither the instruments provided by Her Majesty’s Government, nor the tents and arms, had as yet arrived. But Mr. Overweg had a good sextant, and[18] I a good chronometer, and we were both of us provided with tolerably good compasses, thermometers, and an aneroid barometer. Mr. Frederic Warrington, too, was good enough to lend us a tent.

We had determined to start in the afternoon of the 4th of February, 1850, so as to pass the first night in Ghargásh; but meeting with delays, we did not leave the town till after sunset. We preferred encamping, therefore, in the Meshíah, a little beyond the mosque, under the palm-trees, little knowing at the time what an opportunity we had lost of spending a very cheerful evening.

February 5th.Soon after starting, we emerged from the palm-groves which constitute the charm of Tripoli, and continued our march over the rocky ground. Being a little in advance with the shoush, I halted to wait for the rest, when a very peculiar cry, that issued from the old Roman building on the road-side, called “Kasr el Jahalíyeh,” perplexed us for a moment. But we soon learnt, to our great surprise, not unmixed with regret, that it was our kind friend Frederic Warrington, who had been waiting for us here the whole night. From the top of the ruin, which stands on an isolated rock left purposely in the midst of a quarry, there is a widely extensive view. It appears that, before the Arabs built the castle, this site was occupied by Roman sepulchres. A little further on we passed the stone of Sidi ʿArífa. This stone had fallen upon the head of a workman who was digging a well. The workman, so runs the[19] legend, escaped unhurt; and at Sidi ʿArífa’s word the stone once more sprung to the surface. Further on, near the sea-shore, we passed the chapel of Sidi Salah, who is said to have drawn by magic to his feet, from the bottom of the sea, a quantity of fish ready dressed.

From this point our kind friend Mr. Frederic Warrington returned with his followers to the town, and we were left to ourselves. We then turned off from the road, and entered the fine date-plantation of Zenzúr, celebrated in the fourteenth century, as one of the finest districts of Barbary, by the Sheikh e’ Tijáni, passing by a great magazine of corn, and a mouldering clay-built castle, in which were quartered a body of horsemen of the Urshefāna. Fine olive-trees pleasingly alternated with the palm-grove, while the borders of the broad sandy paths were neatly fenced with the Cactus opuntia. Having passed our former place of encampment in Sayáda, we were agreeably surprised to see at the western end of the plantation a few new gardens in course of formation; for there is a tax, levied not on the produce of the tree, but on the tree itself, which naturally stands in the way of new plantations.

Having halted for a short time at noon near the little oasis of Sidi Ghár, where the ground was beautifully adorned with a profusion of lilies; and having passed Jedaim, we encamped towards evening in the wide courtyard of the Kasr Gamúda, where we were[20] kindly received by the Kaimakám Mustapha Bey, whom I was providentially destined to meet twice again, viz. on my outset from, and on my final return to, Fezzan. The whole plantation of Zawíya, of which Gamúda forms a part, is said to contain a hundred and thirty thousand palm-trees.

Ibrahim gave me an interesting account to-day of Negroland. Though a native of Bagirmi, he had rambled much about Mandara, and spoke enthusiastically of the large and strong mountain-town Karawa, his report of which I afterwards found quite true; of the town of Mendif, situated at the foot of the great mountain of the same name; and of Mora, which he represented as very unsafe on account of bands of robbers,—a report which has been entirely confirmed by Mr. Vogel. Our chief interest at that time was concentrated upon Mandara, which was then supposed to be the beginning of the mountainous zone of Central Africa.

Wednesday, February 6th.While the camels were pursuing the direct track, we ourselves, leaving our former road, which was parallel to the sea-coast, and turning gradually towards the south, made a circuit through the plantation, in order to procure a supply of dates and corn, as we were about to enter on the zone of nomadic existence. The morning was very fine, and the ride pleasant. But we had hardly left the plantation, when we exchanged the firm turf for deep sand-hills which were broken further on by a more favoured soil, where melons were cultivated in[21] great plenty; and again, about four miles beyond the plantation, the country once more assumed a genial aspect. I heard that many of the inhabitants of Zawiya habitually exchange every summer their more solid town residences for lighter dwellings here in the open air. A little before noon we obtained a fine view over the diversified outlines of the mountains before us.

In the plain there are many favoured spots bearing corn, particularly the country at the foot of Mount Mʿamúra, which forms a very conspicuous object from every side. As we advanced further, the country became well inhabited, and everywhere, at some distance from the path, were seen encampments of the tribe of the Belása who occupy all the grounds between the Urshefána and the Bu-ʿAjíla, while the Urjímma, a tribe quite distinct from the Urghámma, have their settlements S.W., between the Nuwayíl and the Bu-ʿAjíla. All these Arabs hereabouts provide themselves with water from the well Núr e’ dín, which we left at some distance on our left.

The encampment near which we pitched our tent in the evening belonged to the chief of the Belása, and consisted of seven tents, close to the slope of a small hilly chain. We had scarcely pitched our tent when rain set in, accompanied by a chilly current of air which made the encampment rather uncomfortable. The chief, Mohammed Chélebi, brought us, in the evening, some bazín; the common dish of the[22] Arab of Tripoli. We wanted to regale him with coffee, but, being afraid of touching the hot drink, and perhaps suspicious of poison, he ran away.

Thursday February 7th.Continuing our march southward through the fine and slightly undulating district of El Habl, where water is found in several wells, at the depth of from fifteen to sixteen fathoms, we gradually approached the mountain-chain. The strong wind, which filled the whole air with sand, prevented us from obtaining a very interesting view from a considerable eminence called el Ghunna, the terminating and culminating point of a small chain of hills, which we ascended. For the same reason, when I and Ibrahim, after lingering some time on this interesting spot, started after our camels, we lost our way entirely, the tracks of our little caravan being totally effaced, and no path traceable over the undulating sandy ground. At length we reached firmer grassy soil, and, falling in with the path, overtook our people at the “Bir el Ghánem.”

Hence we went straight towards the slope of the mountains, and after little more than an hour’s march reached the first advanced hill of the chain, and began to enter on it by going up one of the wadis which open from its flanks. It takes its name from the ethel (Tamarix orientalis), which here and there breaks the monotony of the scene, and gradually widens to a considerable plain bounded by majestic ridges. From this plain we descended into the deep and rugged ravine of the large Wadi[23] Sheikh, the abrupt cliffs of which presented to view beautiful layers of red and white sandstone, with a lower horizontal layer of limestone, and we looked out for a well-sheltered place, as the cold wind was very disagreeable. The wadi has its name from its vicinity to the chapel, or zawiya, of the Merábet Bu-Máti, to which is attached a large school.

Friday, February 8th.On setting out from this hollow we ascended the other side, and soon obtained an interesting view of the varied outlines of the mountains before us, with several half-deserted castles of the Arab middle ages on the summits of the hills. The castle of the Welád Merabetín, used by the neighbouring tribes chiefly as a granary, has been twice destroyed by the Turks; but on the occasion of nuptial festivities, the Arabs, in conformity with ancient usage, still fire their muskets from above the castle. The inhabitants of these mountains, who have a strong feeling of liberty, cling to their ancient customs with great fondness.

We descended again into Wadi Sheikh, which, winding round, crossed our path once more. The regular layers of limestone, which present a good many fossils, with here and there a layer of marl, form here, during heavy rains, a pretty little cascade at the foot of the cliffs. We lost much time by getting entangled in a branch of the wadi, which had no outlet, but exhibited the wild scenery of a glen, worn by the torrents which occasionally rush down the[24] abrupt rocky cliffs. Having regained the direct road, we had to cross a third time the Wadi Sheikh at the point where it is joined by Wadi Ginna, or Gilla, which also we crossed a little further on. In the fertile zone along the coast, the monotony of the palm-groves becomes almost fatiguing; but here we were much gratified at the sight of the first group of date-trees, which was succeeded by others, and even by a small orchard of fig-trees. Here, as we began to ascend the elevated and abrupt eastern cliffs of the valley, which at first offer only a few patches of cultivated plateau, succeeded further on by olive-trees, a fine view opened before us, extending to the S.E. as far as the famous Roman monument called Enshéd e’ Sufét, which is very conspicuous. Having waited here for our camels, we reached the first village, whose name, “Ta-smeraye,” bears, like that of many others, indubitable proof that the inhabitants of these mountainous districts belong originally to the Berber race, though at present only a few of them speak their native tongue. These people had formerly a pleasant and comfortable abode in this quarter, but having frequently revolted against the Turks, they have been greatly reduced, and their villages at present look like so many heaps of ruins.

Having passed some other hamlets in a similar state of decay, and still going through a pleasant but rather arid country, we reached the oppressor’s stronghold, the “Kasr il Jebel,” as it is generally called, although this part of the mountains bears the[25] special name of Yefren. It lies on the very edge of the steep rocky cliffs, and affords an extensive view over the plain. But though standing in a commanding position, it is itself commanded by a small eminence a few hundred yards eastward, where there was once a large quadrangular structure, now in ruins.

The castle, which at the time of our visit was the chief instrument in the hands of the Turks for overawing the mountaineers, contained a garrison of four hundred soldiers. It has only one bastion with three guns, at the southern corner, and was found by Mr. Overweg to be 2150 feet above the level of the sea. The high cliffs inclosing the valley are most beautifully and regularly stratified in layers of gypsum and limestone; and a man may walk almost round the whole circumference of the ravine on the same layer of the latter stone, which has been left bare,—the gypsum, of frailer texture, having been carried away by the torrents of rain which rush violently down the steep descent. From the little eminence above mentioned, there is a commanding view over the valleys and the high plain towards the south.

After our tent had been pitched, we received a visit from Haj Rashíd, the Kaimakám or governor, who is reckoned the second person in the Bashalík, and has the whole district from Zwára as far as Ghadámes towards the S.W., and the Tarhóna towards the S.E., under his military command. His salary is 4600 mahhbúbs annually, or about 720l. He[26] had previously been Basha of Adana, in Cilicia; and we indulged, to our mutual gratification, in reminiscences of Asia Minor.

Saturday, February 9th.Early in the morning I walked to a higher eminence at some distance eastward from the castle, which had attracted my attention the day before. This conspicuous hill also was formerly crowned with a tower or small castle; but nothing but a solitary rustic dwelling now enlivens the solitude. The view was very extensive, but the strong wind did not allow of exact compass observations. While my companion remained near the castle, engaged in his geological researches, I agreed with our shoush and a Zintáni lad whom I accidentally met here, and who on our journey to Fezzan proved very useful, to undertake a longer excursion towards the west, in order to see something more of this interesting and diversified slope of the plateau.

I was anxious to visit a place called Ta-gherbúst, situated on the north side of the castle, along the slope of a ravine which runs westward into the valley; accordingly, on leaving the site of our encampment, we deviated at first a little northwards. Ta-gherbúst is said to have been a rich and important place in former times. Some of its inhabitants possessed as many as ten slaves; but at present it is a heap of ruins, with scarcely twenty-five inhabited houses. From hence, turning southward, we descended gradually along the steep slope, while above our heads the cliffs rose in picturesque majesty, beautifully adorned by scattered[27] date-trees, which, at every level spot, sprung forth from the rocky ground, and gave to the whole scene a very charming character. A fountain which gushed out from a cavern on a little terrace at the foot of the precipice, and fed a handsome group of date-trees, was one of the most beautiful objects that can be imagined.