Large-size versions of illustrations are available by clicking on them.

General table of contents — Narrative in Index — Itineraries in Index

TRAVELS

AND DISCOVERIES

IN

NORTH

AND CENTRAL

AFRICA:

BEING A

JOURNAL OF AN EXPEDITION

UNDERTAKEN

UNDER THE AUSPICES OF H.B.M.’S

GOVERNMENT,

IN THE YEARS

1849-1855.

BY

HENRY BARTH, Ph.D., D.C.L.

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL AND ASIATIC

SOCIETIES,

&c. &c.

IN FIVE VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

LONGMAN, BROWN, GREEN, LONGMANS, & ROBERTS.

1857.

The right of translation is reserved.

London:

Printed by Spottiswoode & Co.

New-street Square.

[iii]CONTENTS

OF

THE SECOND VOLUME.

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Page | |

| Separation of the Travellers. — The Border Districts of the Independent Pagan Confederation. — Tasáwa | 1 |

| Dissembling of the Chief. — His steadfast Character. — Mr. Richardson’s Health. — Separation. — Different Roads to Kanó. — Animated Intercourse. — Native Warfare. — The First Large Tamarind-tree. — Villages and Wells. — Separation from Mr. Overweg. — Improved Scenery. — Encampment at Gozenákko. — Lively Camp-scene. — Native Delicacies. — Revenues of Tasáwa. — Astounding Message. — Visit to Tasáwa. — The Market in Tasáwa. — Náchirá, Ánnur’s Estate. — Character of the People and their Dwellings. — Intrigue defeated. — Counting Shells. — A Petty Sultan. — Dyeing-Pits. | |

| CHAP. XXIII. | |

| Gazáwa. — Residence in Kátsena | 32 |

| An African Dandy. — My Protector Elaiji. — Camp-life. — Fortifications and Market of Gazáwa. — March resumed. — Desolate Wilderness. — Site of Dánkama. — Struggle between Islámism and Paganism. — Encampment near Kátsena. — Estimate of Salt-caravan. — Negro Horsemen. — Equestrian Musicians. — The Governor of Kátsena. — Detained by him. — The Governor’s Wiles. — Disputes. — Who is the “Káfer?” — Clapperton’s Companion. — The Tawáti Bel-Ghét conciliated. — Extortionate Demands. — Subject about the Káfer resumed. — The Presents. — Promenade through the Town. — The Governor’s Wishes. — Taking Leave of him. | |

| [iv]CHAP. XXIV. | |

| Háusa. — History and Description of Kátsena. — Entry into Kanó | 69 |

| The Name Háusa. — Origin of the Háusa Nation. — The seven States. — Origin of the Town of Kátsena. — The Mohammedan Missionary Ben Maghíli. — Kings of Kátsena. — The First Moslim. — The Oldest Quarter. — Magnitude of the Town. — Its Decline. — Salubrious Site and Favourable Situation of Kátsena. — Departure from Kátsena. — Wild State of the Country. — Shibdáwa. — Rich Scenery. — Kusáda. — The Bentang Tree. — Women with Heavy Loads. — Beehives. — Gúrzo. — Approach to Kanó. — Straggling Villages. — Composition of our Troop. — First View of Dalá. — Entering Kanó. | |

| CHAP. XXV. | |

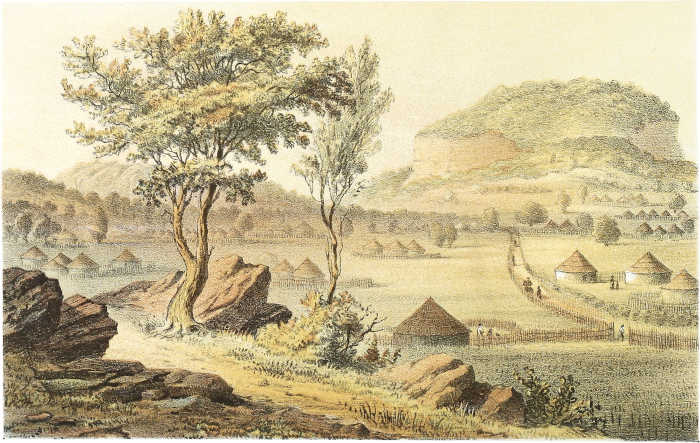

| Residence in Kanó. — View of its Interior. — Its History and Present State. — Commerce | 97 |

| My Situation in Kanó. — Debts. — Projects. — The Commissioner. — Difficulties. — Sickness. — Interior of Kanó; Animated Picture. — The Quarters of the Conquered and the Ruling Race. — The “Serkí” and the Gháladíma. — The Audience. — Presents. — Plan of Kanó. — Street-groups. — Industry. — View from Mount Dalá. — Acquaintances in Kanó. — Meditated Departure. — Historical Sketch of Kanó. — Growth of the Town. — The Quarters of the Town. — Ground-plan of my House. — Population. — Commerce. — Various Kinds of Zénne. — Export of Cloth. — Grand Character of Trade. — Produce. — The Guinea-fowl Shirt. — Leather-work. — Kola-nut. — Slaves. — Natron, Salt, Ivory-trade. — European Goods in Kanó. — The South American Slave-traders. — Small Quantity of Calico. — Silk. — Woollen Cloth. — Beads. — Sugar. — Fire-arms. — Razors. — Arab Dresses. — Copper. — The Shells and the Dollar. — Markets of Kanó. — Revenues. — Administration. — The Conquering Tribe. | |

| CHAP. XXVI. | |

| Starting for Kúkawa. — The Frontier-district | 148 |

| Leaving Kanó quite by myself. — My Trooper. — Get off later. — Domestic Slavery. — Gezáwa. — My Runaway Servant ʿAbd Allah. — The Sheríf and his Attendants. — Mules in Negroland. — Kúka Mairuwá. — Insecurity. — Scarcity of Water. — Natron-trade. — Endurance and Privations of the Traveller. — Arrival at Gerki. — Take Leave of Háusa. — Gúmmel. — Housebuilding. — Antidote. — Market at Gúmmel. — Magnitude of Ilóri.[v] — Two Spanish Dollars. — Depart from Gúmmel. — Benzári. — The Rebel Chief Bokhári. — His Exploits. — The Governor of Máshena. — Letter-carrier’s Mistake. — Curious Talisman. — Manga Warriors. — Wuëlleri. — Scarcity of Water again. — Town of Máshena. — State of the Country. — Cheerful, Out-of-the-way Place. — Álamáy. — Búndi and the Gháladíma. — The Kárda. — Route from Kanó to Álamáy by way of Khadéja. | |

| CHAP. XXVII. | |

| Bórnu Proper | 197 |

| Intercourse. — Change of Life in Negroland. — Region of the Dúm-palm. — The Kúri Ox. — The River Wáni. — Enter Bórnu Proper. — Zurríkuló. — News of the Death of Mr. Richardson. — Sandy Downs. — Déffowa. — Industry. — The Stray Camel. — Town of Wádi. — Good Market and no Provisions. — Hospitable Treatment. — The Banks of the Wáni. — Locusts and Hawks. — Ngurútuwa; Grave of Mr. Richardson. — The Tawárek again. — Aláune. — The Jungles of the Komádugu. — Ruins of Ghámbarú. — A Forest Encampment. — Nomadic Herdsmen. — Abundance of Milk. — Ford of the Komádugu. — Native Ferry-boats. — Khér-Álla, the Border-warfarer. — Changing Guides. — The Runaway Horse. — A Domestic Quarrel. | |

| CHAP. XXVIII. | |

| Arrival in Kúkawa | 240 |

| Peculiar Character of the Alluvial Plains of Bórnu. — The Attentive Woman. — Entrance into Kúkawa. — Servants of the Mission. — Debts of the Mission. — Interview with the Vizier. — Sheikh ʿOmár. — Mr. Richardson’s Property. — Amicable Arrangements. | |

| CHAP. XXIX. | |

| Authenticity and general Character of the History of Bórnu | 253 |

| Documents. — Beginning of written History. — Pedigree of the Bórnu Kings. — Chronology. — Harmony of Facts. — The Séfuwa Dynasty. — Ébn Khaldún. — Makrízí and Ébn Batúta. — Surprising Accuracy of the Chronicle of Bórnu. — Statement of Leo Africanus. — Berber Origin of the Séfuwa. — Form of Government. — The Berber Race. — The Queen Mother. — Indigenous Tribes. — The Tedá or Tebu. — The Soy. — Epochs of Bórnu History. — Greatest Power. — Decline of the Bórnu Empire. — The Kánemíyín. | |

| [vi]CHAP. XXX. | |

| The Capital of Bornu | 283 |

| My Friends. — The Arab Áhmed bel Mejúb. — The Púllo Íbrahím from the Senegal. — Dangerous Medical Practice. — Áhmed the Traveller. — My Bórnu Friends. — The Vizier el Háj Beshír; his Career; his Domestic Establishment; his Leniency. — Debts of the Mission paid. — The English House. — Plague of Insects. — Preparations for a Journey. — Character of Kúkawa. — The Two Towns. — The Great Market. — Business and Concourse. — Defective Currency. — Prices of Provisions. — Fruits. — Camels. — Horses. — Want of Native Industry. — Bórnu Women. — Promenade. | |

| CHAP. XXXI. | |

| The Tsád | 319 |

| Character of the Road to Ngórnu. — Ngórnu. — Searching the Tsád. — Longer Excursion. — Character of the Shores of the Tsád. — The Búdduma and their Boats. — Fresh Water. — Swampy Plains. — Boats of the Búdduma again. — Maduwári. — Dress of the Sugúrti. — Account of the Lake. — Shores of the Creek. — Sóyorum. — Káwa. — Return to Kúkawa. — Servants dismissed. — Mohammed Titíwi the Auspicious Messenger. — Slave-caravan. — Announcement of Rainy Season. — Ride to Gawánge. — Mr. Overweg’s Arrival. — Meeting. — Property restored. — Mercantile Intrigues. — The Sheikh’s Relatives. — Messengers from Ádamáwa. — Anticipated Importance of the Eastern Branch of the Niger — Proposed Journey to Ádamáwa. | |

| CHAP. XXXII. | |

| Setting out on my Journey to Ádamáwa. — The Flat, Swampy Grounds of Bórnu | 351 |

| Leaving Kúkawa. — The Road Southwards. — Inhospitality near the Capital. — Buying with a Shirt. — The Winter Corn. — The Shúwa Arabs. — Múngholo Gezáwa. — Fair Arabs. — Magá District. — The Gámerghú District. — District of Ujé. — Fine Country. — Mábaní. — Pilgrim Traders, Banks of the Yáloë. — First View of the Mountains. — Fúgo Mozári. — Market of Ujé. — Aláwo. — Approach to Mándará. | |

| [vii]CHAP. XXXIII. | |

| The Border-country of the Marghí | 374 |

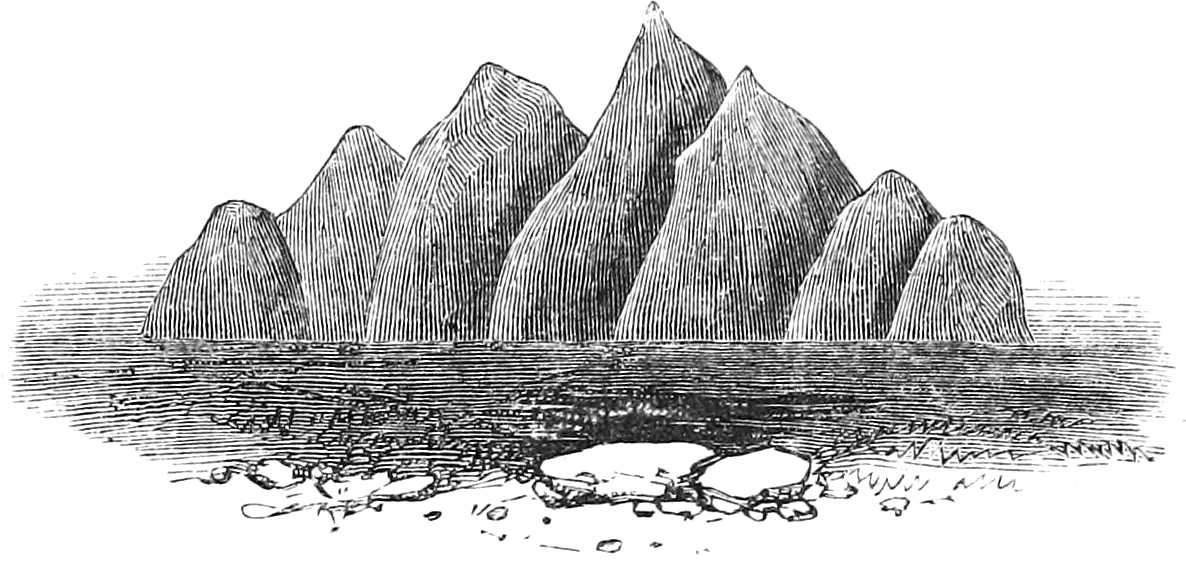

| Question about Snowy Mountains. — The Blacksmith. — Shámo District. — A Storm. — Molghoy. — The Southern Molghoy. — Large Kúrna-trees. — Structure of the Huts. — Deviations from Negro Type. — The Marghí, their Attire and Language. — Edible Wild Fruits. — The Baobab. — Beautiful Scenery. — Íssege. — Spirit of the Natives. — Degenerate Fúlbe. — The Lake. — View of Mount Míndif. — Wándalá Mountains. — Route to Sugúr. — The Marghí Tribe. — Scientific Dispute. — Unsafe Wilderness. — Unwholesome Water. — The Return of the Slave Girl. — The Bábir Tribe. — Laháula. — The Idol. — Alarm. — Abundance of Vegetable Butter. — Serious March. — The Báza Tribe. — The Dividing Range. — Úba. — The New Colony. | |

| CHAP. XXXIV. | |

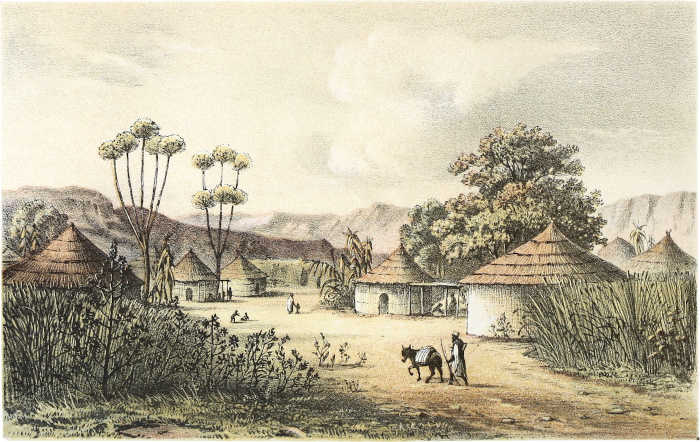

| Ádamáwa. Mohammedan Settlements in the Heart of Central Africa | 414 |

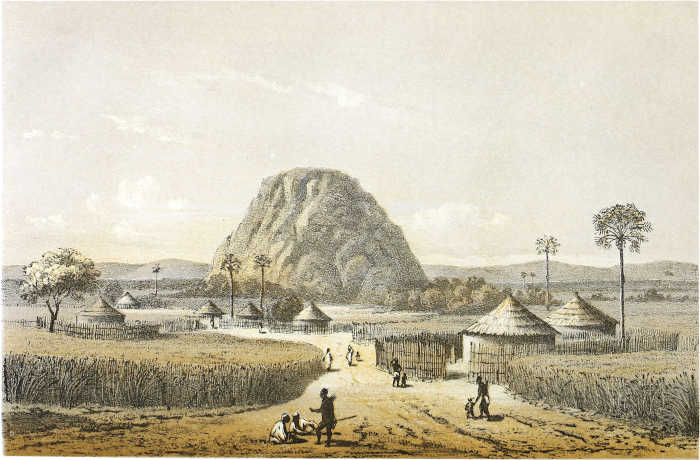

| The Conquering Tribe. — The Granite Hills. — Valley and Mountain-chain. — Isolated Mountain-groups. — Múbi. — The Surrounding Country. — Origin of the Fúlbe. — Bágma and Peculiar Structures. — Camels a Novelty. — Compliment paid to the Christian. — Mbutúdi. — Fúlbe Way of Saluting. — The Déléb-palm (Borassus flabelliformis?) and its Fruit. — The Granite Mount. — Simplicity of Manners. — Mount Hólma. — Legéro. — Edible Productions. — Ground-nut Diet. — Badaníjo. — Fertile Vale. — Temporary Scarcity. — Kurúlu. — Red and white Sorghum. — Saráwu Beréberé. — Comfortable Quarters. — Accurate Description. — Important Situation of Saráwu. — Tebu Traders. — Fair Negroes. — Market of Saráwu. — Saráwu Fulfúlde. — The Mansion. — The Blind Governor. — Principal Men in Yóla. — Mount Konkel. — Bélem. — An Arab Adventurer. — Rich Vegetation. — The young Púllo. — Old Mʿallem Dalíli. — Arab Colony. — A Country for Colonies. — Ruined Village (Melágo). — Gastronomic Discussion. — Máyo Tíyel. — The Bátta Tribe. — Sulléri. — Inhospitable Reception. | |

| CHAP. XXXV. | |

| The Meeting of the Waters. — The Bénuwé and Fáro | 463 |

| Approach to the River. — Mount Alantíka and the Bénuwé. — The Tépe or “Junction.” — The great Arm of the Kwára. — The Traveller’s Pursuits. — Highroad of Commerce. — The Frail Canoes. — Bathing in[viii] the Bénuwé. — The Passage. — The River Fáro; its Current. — Floods and Fall of the River. — Chabajáure. — Densely inhabited District. — Mount Bágelé. — The Backwater. — Ribágo. — Cultivation of Rice. — The Bátta Language. — Inundation. — Yebbórewó. — Mount Bágelé and Island. — Reach Yóla. | |

| CHAP. XXXVI. | |

| My Reception in Yóla. — Short Stay. — Dismissal | 485 |

| Inauspicious Entrance. — Curiosity of Natives. — Quarters. — An Arab Traveller to Lake Nyassa. — The Governor Mohammed Lowel. — The Audience. — The Mission repulsed. — The Governor’s Brother Mansúr. — Ordered to withdraw. — Begin my Return-Journey. — Character of Yóla. — Slavery. — Extent of Fúmbiná. — Elevation and Climate. — Vegetable and Animal Kingdom. — Principal Chiefs of the Country. — Tribes; the Bátta, the Chámba, and other Tribes. | |

| CHAP. XXXVII. | |

| My Journey Home from Ádamáwa | 515 |

| Start from Ribágo. — Hospitable Treatment in Sulléri. — Demsa-Póha. — The Memorable Campaign Southward. — View of a Native Settlement. — Beautiful Country. — Bélem again. — Mʿallem Dalíli and his Family. — Múglebú. — Múbi. — My Quarters. — Household Furniture. — Úba. — Unsafe Boundary-district. — Laháula. — Íssege. — Iron Ornaments of the Marghí. — Funeral Dance. — Ordeal. — Feeling of Love. — A Party going to Sacrifice. — Arrival at Yerímarí. — Villages of the Gámerghú. — Ujé Kásukulá. — Difference of Climate. — Plants. — Huts. — Plains of Bórnu Proper. — Seizing a Hut. — African Schoolboys. — A wandering Tribe. — Town and Country. — Guineaworm. — Thunder-storm. — People returning from Market. — Múnghono. — Return to Kúkawa. | |

| APPENDIX. | |

| I. | |

| Quarters of the Town of Kátsena | 555 |

| II. | |

| Chief Places in the Province of Kátsena | 557 |

| [ix]III. | |

| Chief Places in the Province of Kanó, and Routes diverging from Kanó in various Directions, principally towards the South | 558 |

| IV. | |

| Collection of Itineraries passing through the various Districts of Ádamáwa | 587 |

| V. | |

| Chronological Table, | |

| Containing a List of the Séfuwa, or Kings of Bórnu descended from Séf, with the few historical facts and events under their respective reigns, that have come to our knowledge | 633 |

| VI. | |

| Fragments of a Meteorological Register | 673 |

[x]LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

IN

THE SECOND VOLUME.

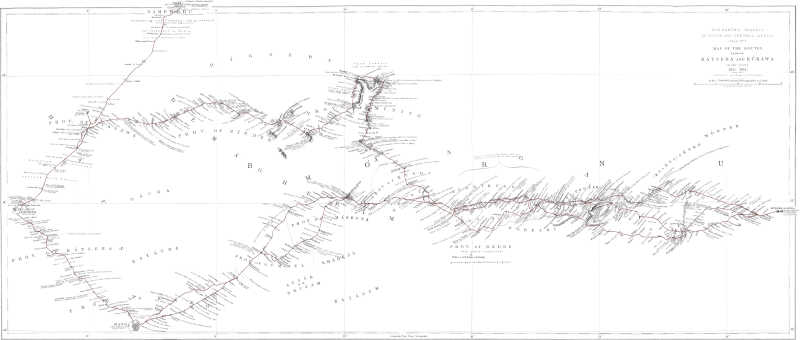

| MAPS. | |||

| Page | |||

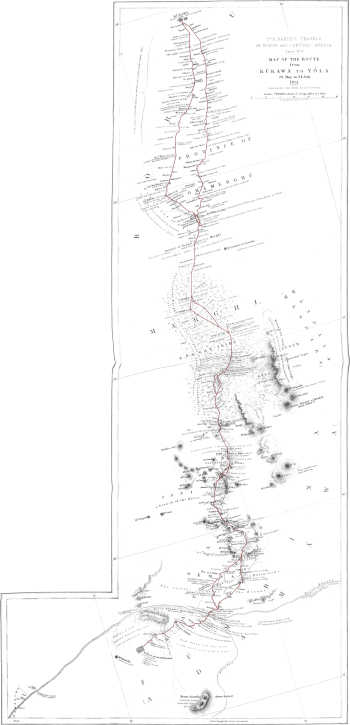

| VII. | Routes between Kátsena and Kúkawa | i | |

| VIII. | Route from Kúkawa to Yóla | 351 | |

| PLATES. | |||

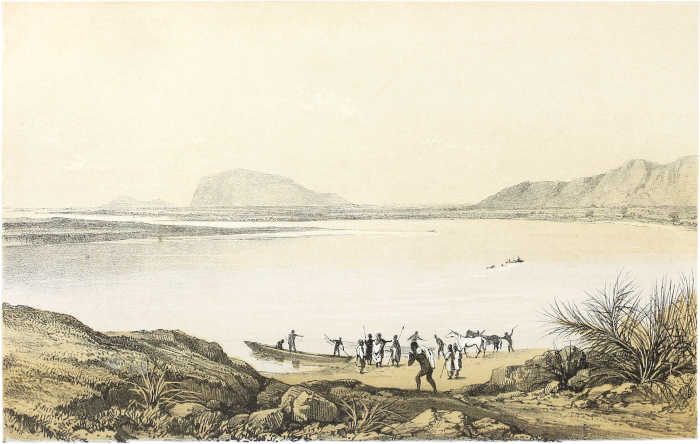

| 1. | Tépe, the confluence of the Bénuwé and Fáro | Frontispiece | |

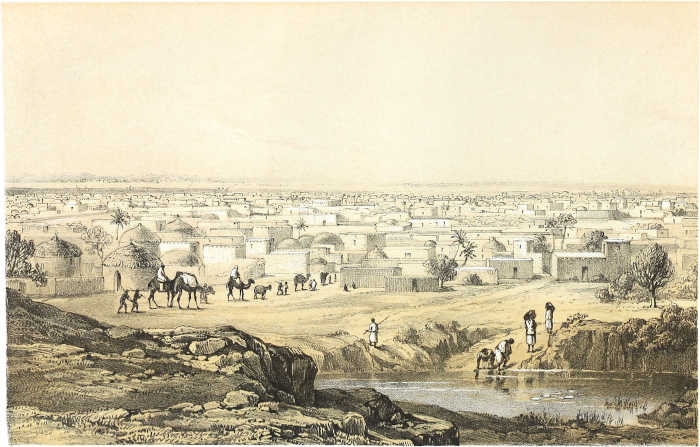

| 2. | Kanó from Mount Dalá | to face | 111 |

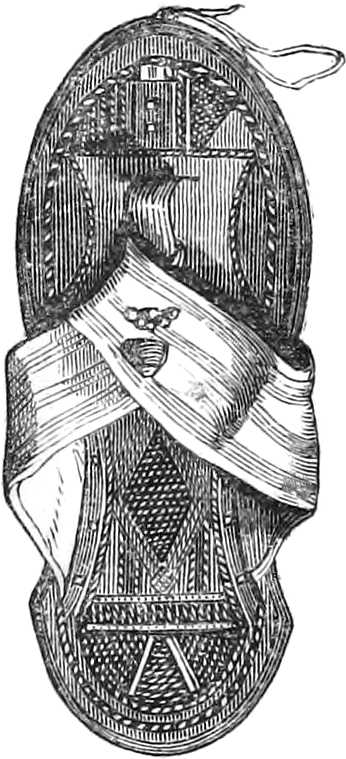

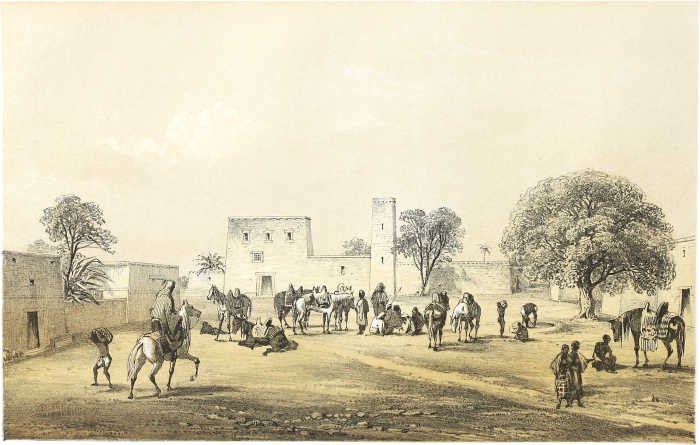

| 3. | Dendal in Kúkawa | „ | 243 |

| 4. | Kálu-Kemé, the open Water of the Tsád | „ | 331 |

| 5. | Shores of Lake Tsád | „ | 332 |

| 6. | Mbutúdi | „ | 425 |

| 7. | Demsa-póha | „ | 521 |

| 8. | Múglebu | „ | 525 |

| WOODCUTS. | |||

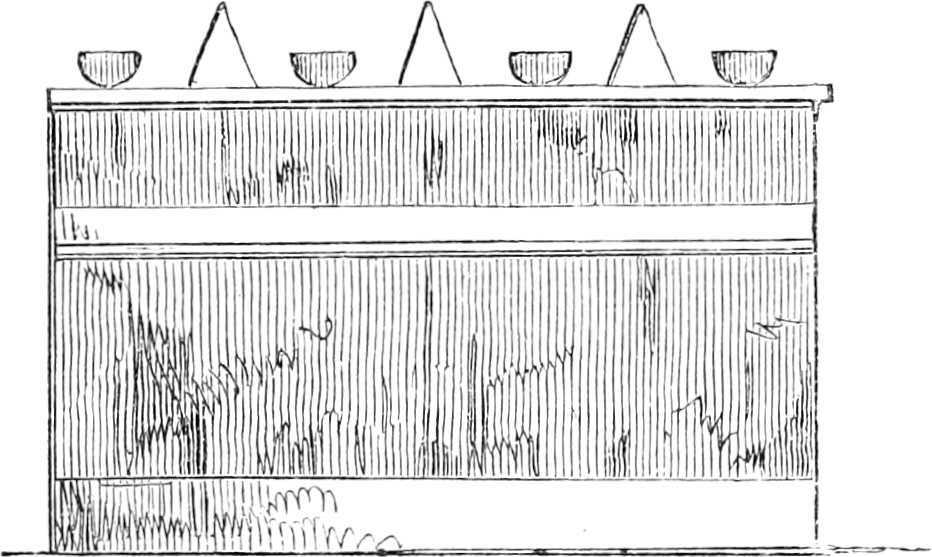

| Corn-stack | 5 | ||

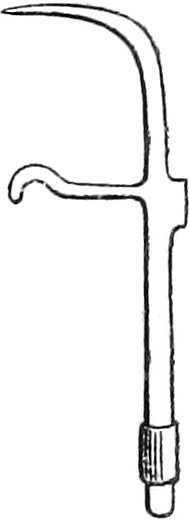

| Negro Stirrup | 46 | ||

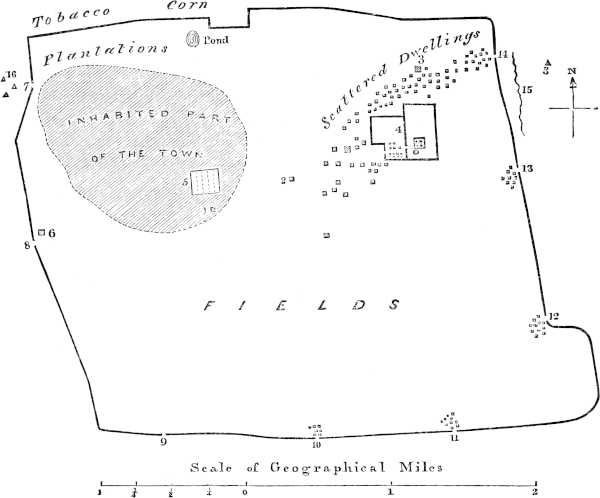

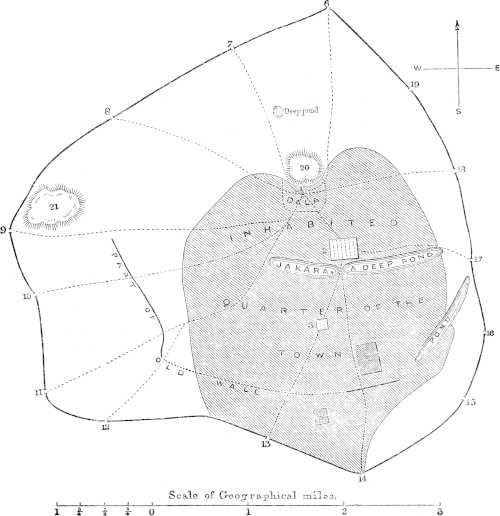

| Ground-plan of the Town of Kátsena | 79 | ||

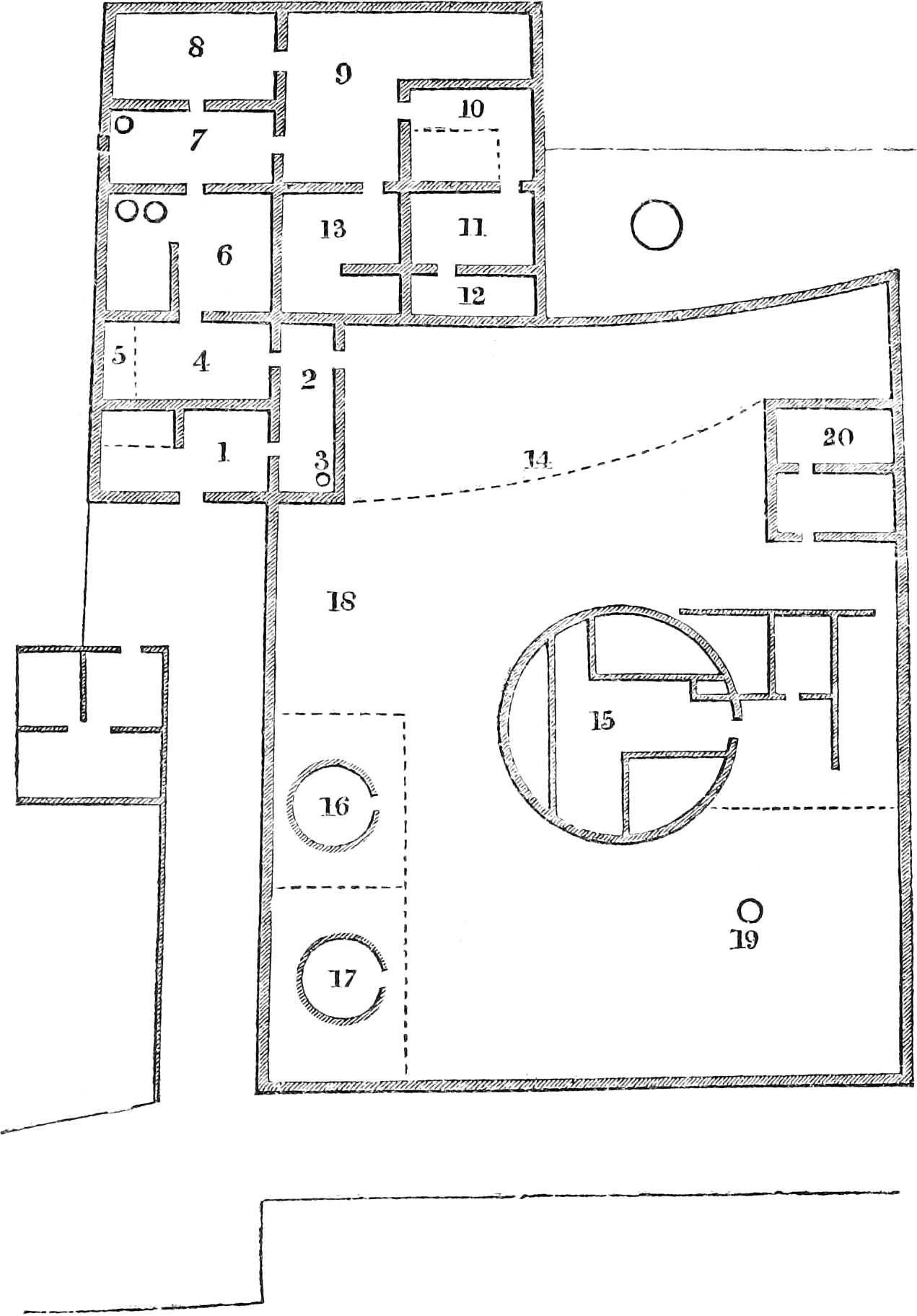

| Ground-plan of the Town of Kanó | 107 | ||

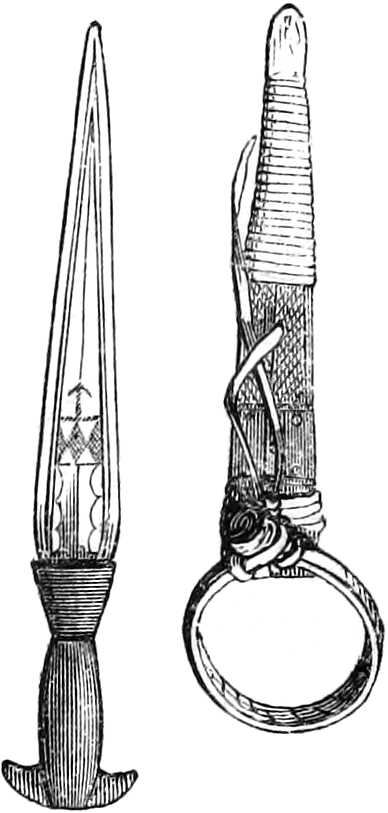

| Dagger and Scabbard | 110 | ||

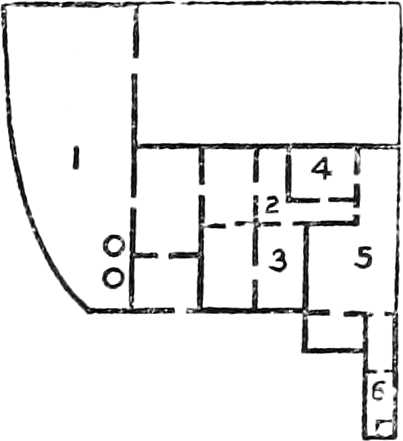

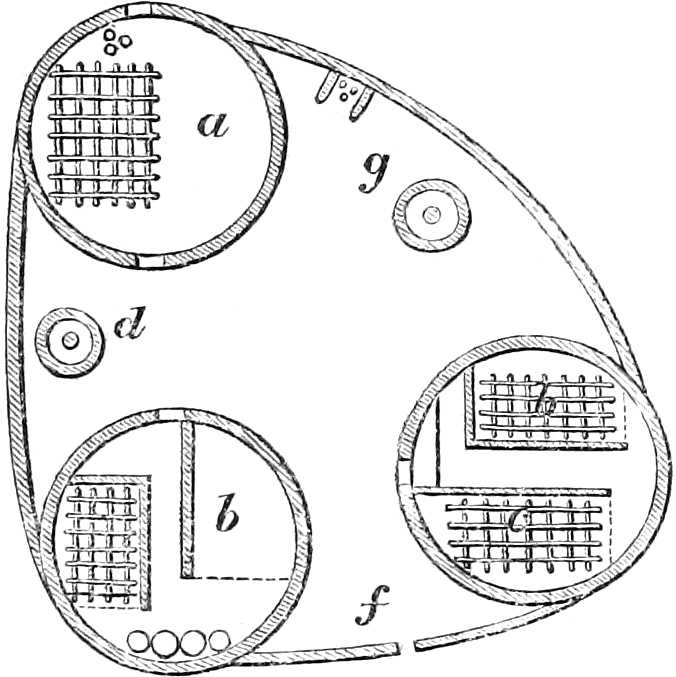

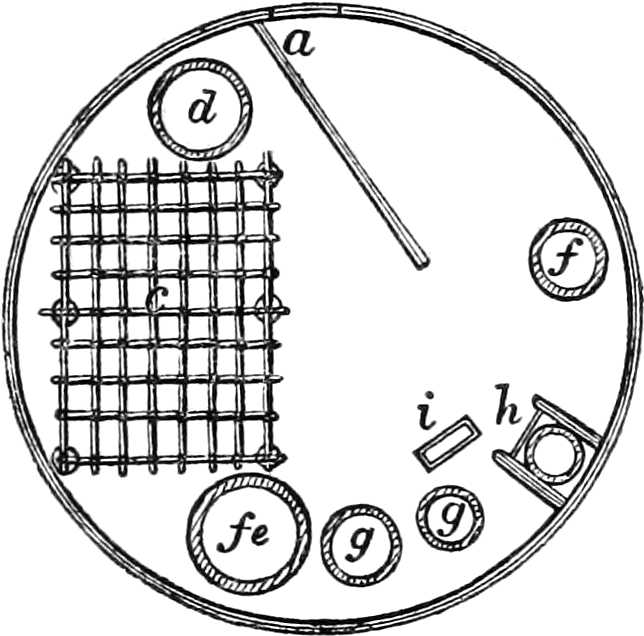

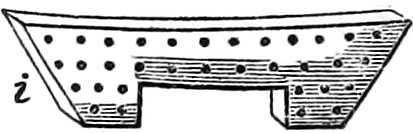

| [xi]Ground-plan of my House in Kanó | 124 | ||

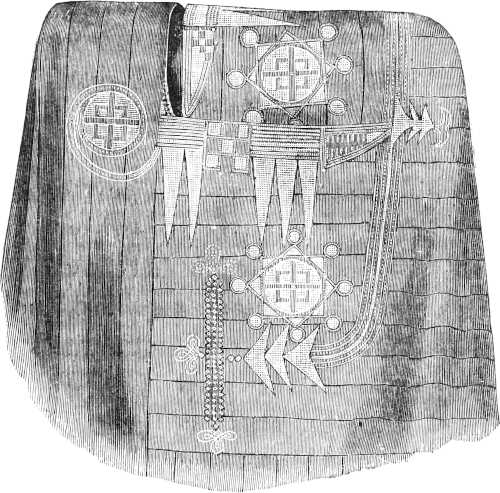

| Guinea-fowl Shirt | 129 | ||

| Sandals | 130 | ||

| Leather Pocket | ib. | ||

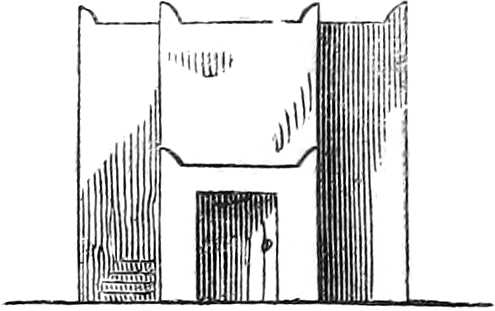

| Henhouse | 207 | ||

| Ground-plan of House in Kúkawa | 299 | ||

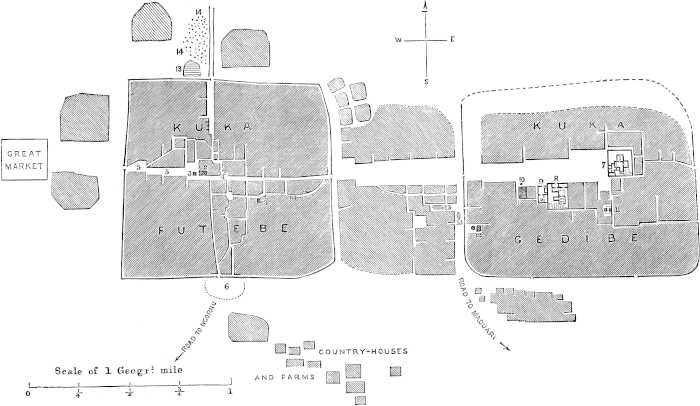

| Ground-plan of the Town of Kúkawa | 304 | ||

| The Seghëum of the Marghí | 384 | ||

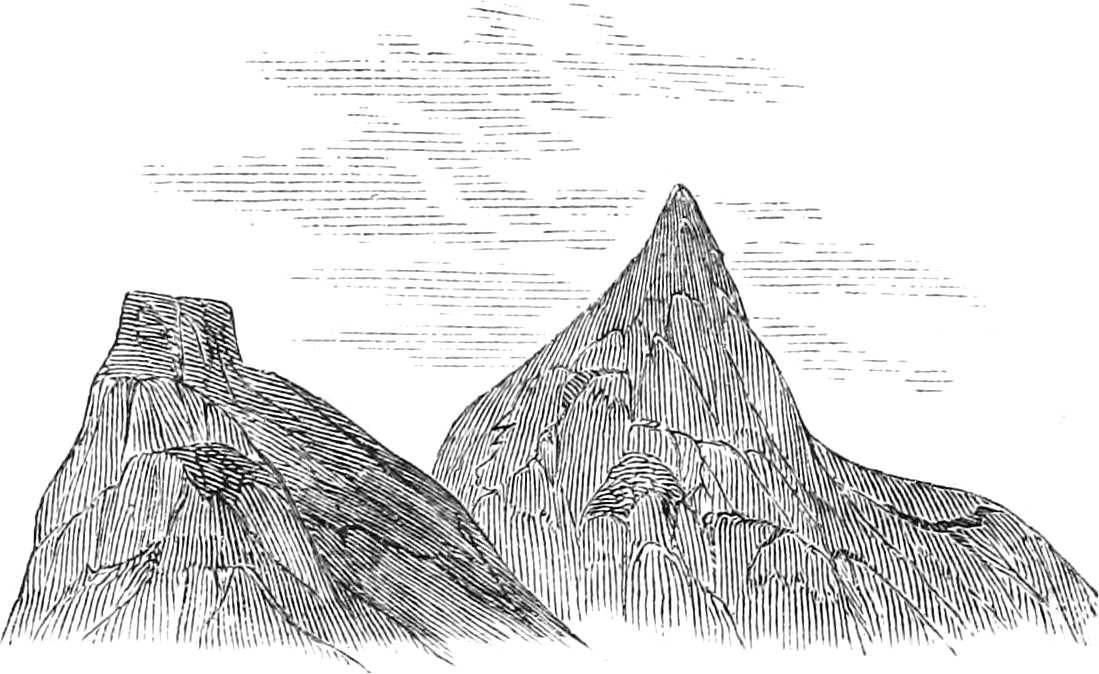

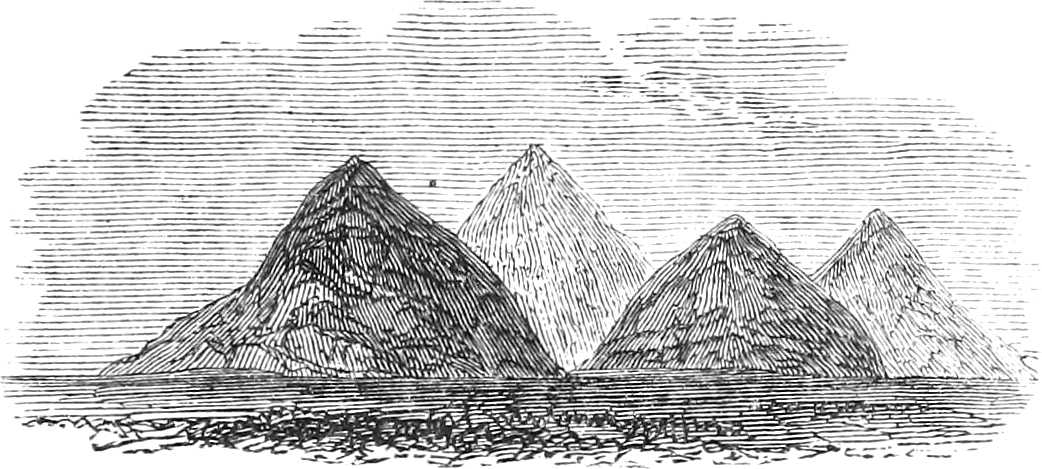

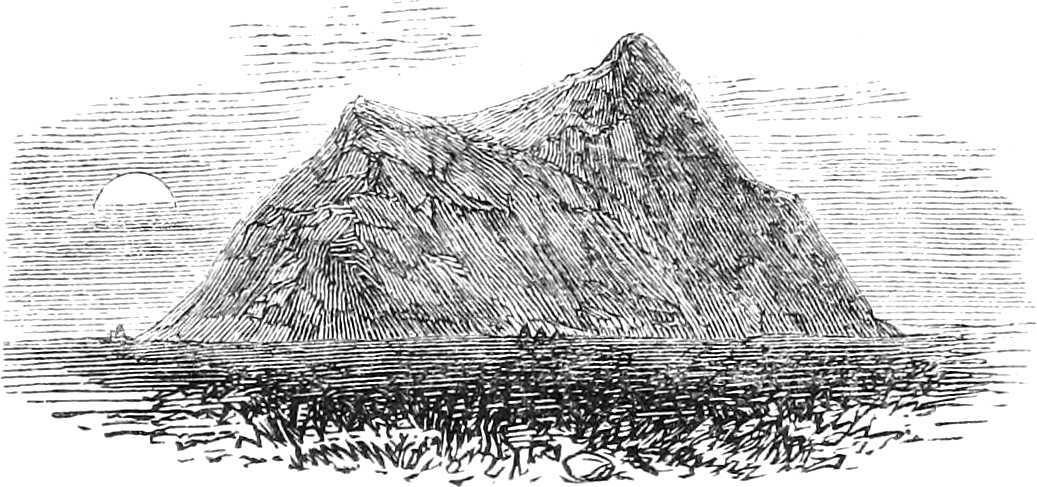

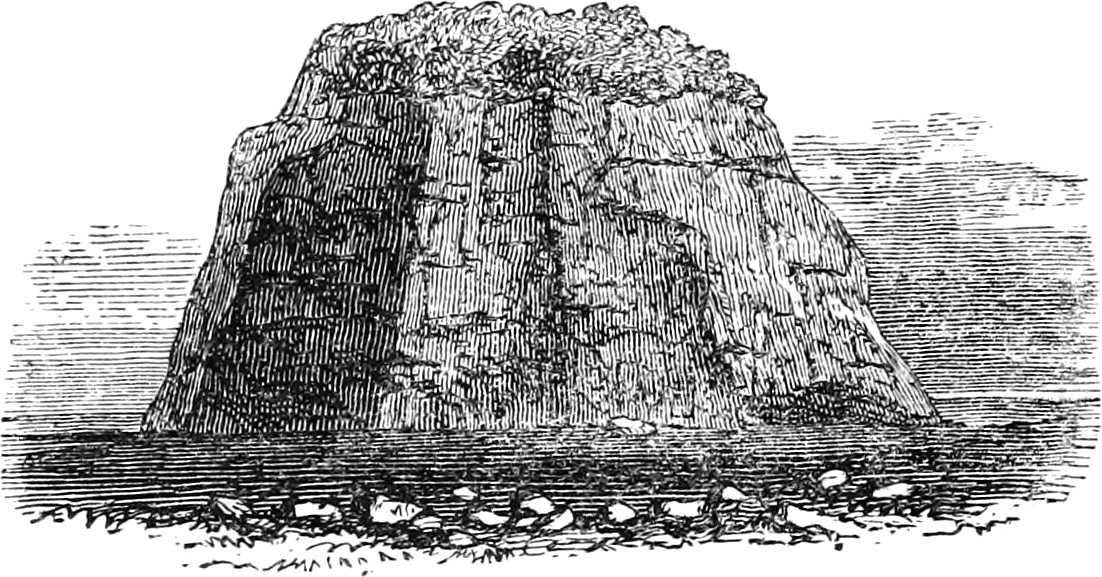

| Double Peak of Mount Míndif | 396 | ||

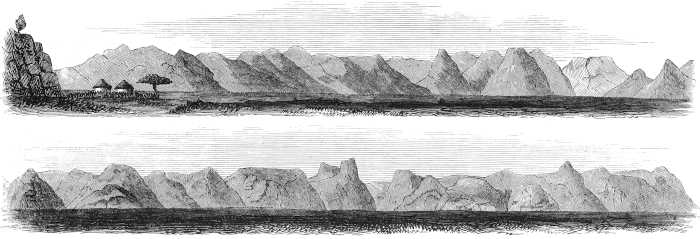

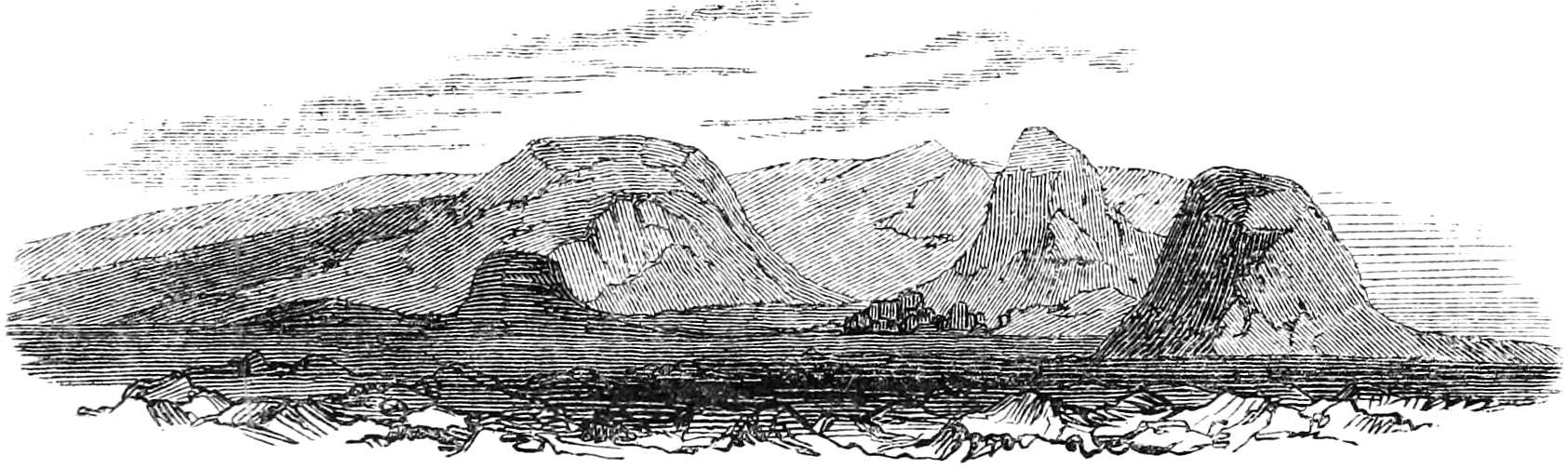

| View of Mountain-chain of Úba | 416 | ||

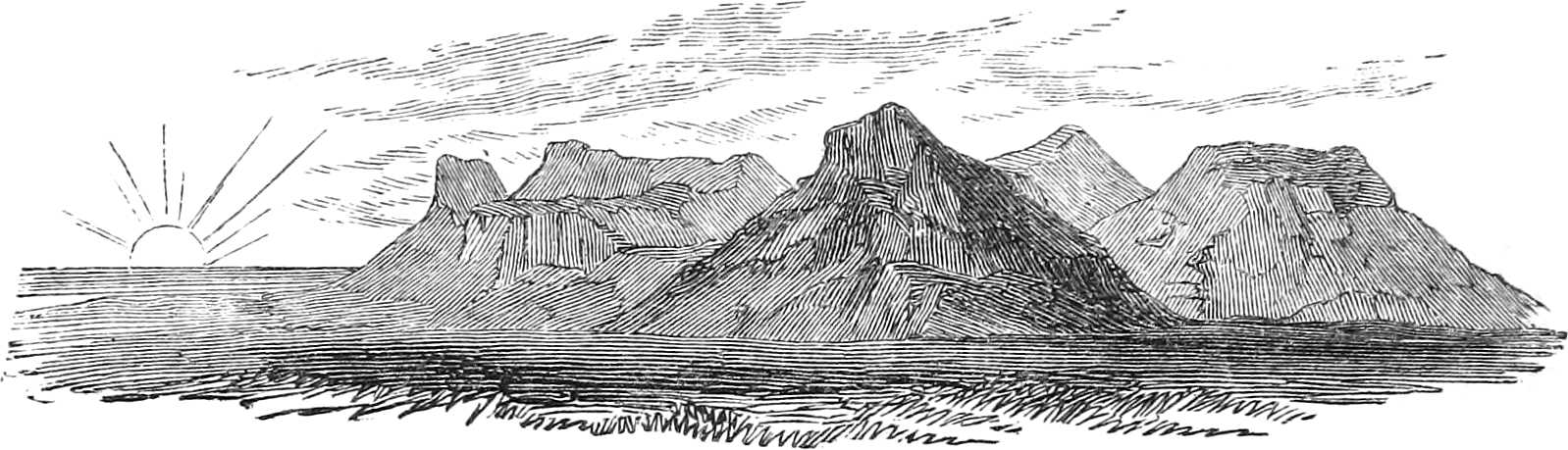

| Mountain | 418 | ||

| Another Mountain | 419 | ||

| Mount Kilba-Gáya | ib. | ||

| Mountain-chain, Fingting | 421 | ||

| Mount Hólma | 431 | ||

| Mount Kurúlu | 437 | ||

| Ground-plan of Huts | 439 | ||

| Couch-screen | 441 | ||

| Picturesque Cone | 442 | ||

| Mountain-range beyond Saráwu | 450 | ||

| Mount Kónkel | 451 | ||

| The Governor’s Audience-hall | 490 | ||

| Picturesque Cone | 518 | ||

| Ground-plan of Hut in Múbi | 527 | ||

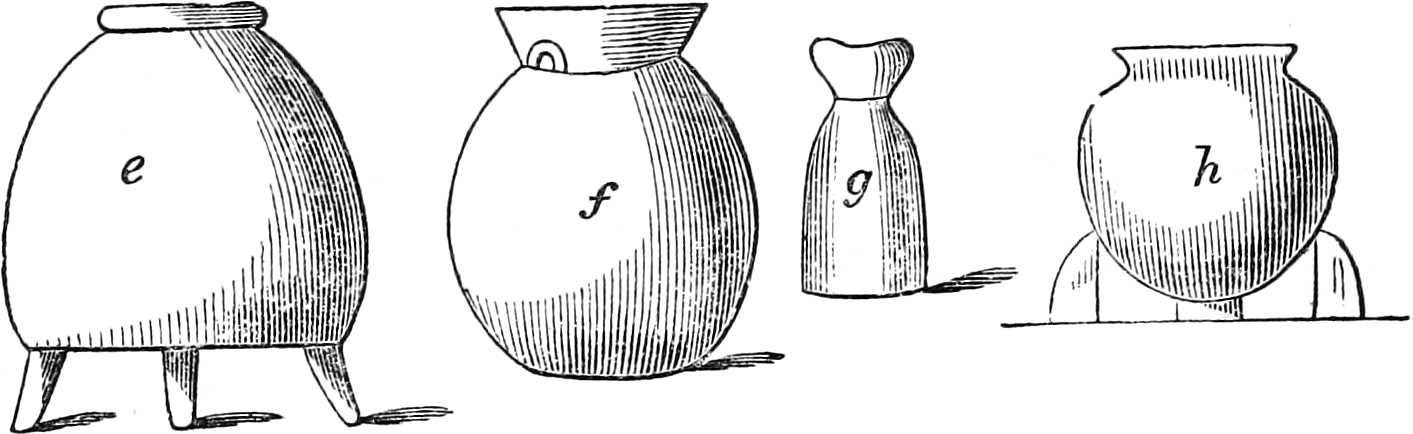

| Household Furniture | 528 | ||

| Hand-bill | 532 | ||

| Shield | 537 | ||

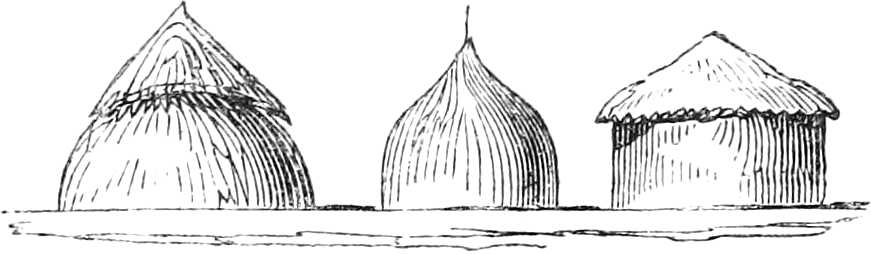

| Different Shape of Huts | 549 | ||

DR. BARTH’S TRAVELS

IN NORTH AND CENTRAL AFRICA

Sheet No. 7.

MAP OF THE

ROUTES

between

KÁTSENA AND KÚKAWA

in the years

1851-1854.

Constructed and drawn by A. Petermann.

Engraved by E. Weller, Duke Strt. Bloomsbury.

London, Longman & Co.

[1]TRAVELS AND

DISCOVERIES

IN

AFRICA.

CHAPTER XXII.

SEPARATION OF THE TRAVELLERS. — THE BORDER DISTRICTS OF THE INDEPENDENT PAGAN CONFEDERATION. — TASÁWA.

Friday, Jan. 10th, 1851.The important day had arrived when we were to separate not only from each other, but also from the old chief Ánnur, upon whom our fortunes had been dependent for so long a period. Having concealed his real intentions till the very last moment, he at length, with seeming reluctance, pretended that he was going first to Zínder. He confided me, therefore, to the care of his brother Elaiji, a most amiable old man, only a year younger than himself, but of a very different character, who was to take the lead of the salt-caravan to Kanó; and he promised me that I should arrive there in safety.

[2]I had been so fortunate as to secure for myself, as far as that place, the services of Gajére, who was settled in Tágelel, where he was regarded as Ánnur’s chief slave, or overseer (“babá-n-báwa”). This man I hired, together with a mare of his, for myself, and a very fine pack-ox for that part of my luggage which my faithful camel, the Bu-Séfi, was unable to carry. Ánnur, I must say, behaved excellently towards me in this matter; for, having called me and Gajére into his presence, he presented his trusty servant, before all the people, with a red bernús on my account, enjoining him in the strictest terms to see me safe to Kanó.

And so I separated from our worthy old friend with deep and sincere regret. He was a most interesting specimen of an able politician and a peaceful ruler in the midst of wild, lawless hordes; and I must do him the justice of declaring that he behaved, on the whole, exceedingly well towards us. I cannot avoid expressing the sorrow I afterwards felt on account of the step which Mr. Richardson thought himself justified in taking as soon as he had passed from the hands of Ánnur into those of the authorities of Bórnu, viz., to urge the sheikh of that country to claim restitution from the former, not only for the value of the things taken from us by the bordering tribes of the desert, but even of part of the sum which we had paid to Ánnur himself. Such conduct, it appeared to me, was not only impolitic, but unfair. It was impolitic, because the claim[3] could be of no avail, and would only serve to alienate from us a man whom we had succeeded in making our friend; and it was unfair, for, although the sum which we had given to the chief was rather large in proportion to our limited means, we were not compelled to pay it, but were simply given to understand that, if we wanted the chief himself to accompany us, we must contribute so much. I became fully aware of the unfavourable effect which Mr. Richardson’s proceedings in this respect produced, on the occasion of a visit which I paid the old chief in the beginning of the year 1853, when passing through Zínder on my way to Timbúktu. He then mentioned the circumstance with much feeling, and asked me if, judging from his whole behaviour towards us, he had deserved to be treated as a robber.

But to return to Tágelel, when I shook hands with the “sófo” he was sitting, like a patriarch of old, in the midst of his slaves and free men, male and female, and was dividing amongst them presents, such as shawls and turkedies, but principally painted armrings of clay, imported from Egypt, and of which the women of these districts are passionately fond. Mr. Richardson being ready to start, I took a hearty farewell of him, fixing our next place of meeting in Kúkawa, about the first of April. He was tolerably well at the time, although he had shown evident symptoms of being greatly affected by the change from the fine fresh air of the mountainous district of Aïr to the sultry climate of the fertile lands of Negroland;[4] and he was quite incapable of bearing the heat of the sun, for which reason he always carried an umbrella, instead of accustoming himself to it by degrees. There was some sinister foreboding in the circumstance that I did not feel sufficient confidence to intrust to his care a parcel for Europe. I had sealed it expressly that he might take it with him to Kúkawa, and send it off from that place with his own despatches immediately after his arrival; but at the moment of parting I preferred taking it myself to Kanó. All my best friends amongst the Kél-owí were also going to Zínder, in order, as they said, to accompany their master, although only a small part of the salt-caravan followed that route. Overweg and I remained together for two or three days longer.

I felt happy in the extreme when I found myself once more on horseback, however deficient in beauty my little mare might be; for few energetic Europeans, I think, will relish travelling for any length of time on camel’s back, as they are far too dependent on the caprice of the animal. We set out at half-past seven o’clock, and soon passed on our right a village, and then a second one, which I think was Dákari, where a noble lady of handsome figure, and well mounted upon a bullock, joined the caravan. She was seated in a most comfortable large chair, which was fastened on the bullock’s back. We afterwards passed on our right the town of Olalówa, situated on a low range of hills. In the lower plain[5] into which we next descended, I observed the first regular ant-hill. Small groups of corn-stacks, or rumbús, further on dotted a depression or hollow, which was encompassed on both sides with gently-sloping hills. Here I had to leave the path of the caravan with my new companion Gajére, who was riding the bullock, in order to water our two beasts, a duty which now demanded our chief attention every day.

At length we reached the watering-place of Gílmirám, consisting of a group of not less than twenty wells, but all nearly dry. The district of Damerghú must sometimes suffer greatly from drought. The horses and cattle of the village were just coming to be watered; what time and pains it must take to satisfy a whole herd, when we were scarcely able to water our two animals! Passing along through thick underwood, where the “kálgo,” with its large dry leaves of olive hue, and its long red pods similar to those of the kharúb-tree, but much larger, predominated almost exclusively, and leaving the village Maihánkuba on our right, we at last overtook the caravan; for the Ásbenáwa pack-oxen are capable of carrying heavy loads at a very expeditious pace, and in this respect leave far behind them the pack-oxen of the fertile regions of Negroland. We now kept along through the woody region, where the tree “góshi,” with an edible fruit, was most frequent. We encamped in a thickly-wooded hollow, when my[6] sociable companion Gajére, as well by the care he took for our evening fire (which he arranged in the most scientific way) as by the information he gave me with regard to the routes leading from Zínder to Kanó, contributed greatly to the comfort and cheerfulness of our bivouac. I first learned from him that there are four different routes from Zínder to Kanó, one route, the westernmost, passing by Dáura; the second, passing by Kazáure; the third, by Garú-n-Gedúnia; the fourth, by Gúmmel (or, as he pronounced it, Gúmiel[1]), gari-n-serki-n-Da-n-Tanóma, this being the easternmost and longest route. Gajére himself was only acquainted with the third route, the stations of which are as follows.

Starting from Zínder you sleep the first night in Gógo, the second in Mokókia, the third in Zólunzólun, the fourth in Magáriá, the fifth in Túnfushí, the sixth in Garú-n-Gedúnia, from whence it is three days’ journey to Kanó.

Saturday, January 11th.My people, Gajére, and myself started considerably in advance of the caravan, in order to water the animals at our leisure, and fill the waterskins. It was a beautiful morning, and our march a most pleasant one; a tall sort of grass called “gámba” covered the whole ground. Thus we went on cheerfully, passing by a well at present dry, situated in a small hollow and surrounded with fine trees which were enlivened by numbers of Guinea fowl and wild[7] pigeons. Beyond this spot the country became more open; and about five miles from the well we reached the pond or “tébki-n-rúwa Kúdura,” close on the right of our path. It was already partly dried up, and the water had quite a milky colour from the nature of the ground, which consists of a whitish clay; but during the rainy season, and for some time afterwards, when all the trees which surround it in its dry state stand in the midst of the water, it is of considerable size. There are a great many kálgo-trees here. We also met a small troop of men very characteristic of the country we had entered, being wanton in behaviour and light in dress, having nothing on but short shirts (the colour of which had once been dark blue) and diminutive straw hats, while all their luggage consisted of a small leathern bag with pounded “géro” or millet, some gourd bottles to contain the fura, besides two or three drinking-vessels. One of them, an exceedingly tall fellow, rode a horse scarcely able to carry him, though the cavalier was almost as lean as his Rosinante. Soon afterwards the pond became enlivened by the arrival of a caravan of pack-oxen, everything indicating that we had reached a region where intercourse was easy and continuous.

We remained here nearly two hours, till the “aïri” came up, when we joined it, and soon discovered the reason of their being so long; for in the thick underwood the long strings of camels could not proceed fast, and the stoppages were frequent. We then met[8] another small caravan. At a quarter past four in the afternoon we encamped in a locality called Amsúsu, in the midst of the forest. We were busy pitching the tent, when a body of about sixteen horsemen came up, all dressed in the Tawárek fashion, but plainly indicating their intermixture with the Háusa people by their less muscular frame, and by the variety of their dress; and in fact they all belonged to that curious mulatto tribe called Búzu (pl. Búzawe). They were going on a “yáki,” but whether against the Awelímmiden or the Féllani I could not learn at the time; the latter, however, proved to be the case.

The earth hereabouts was filled with a peculiar kind of small worms, which greatly annoyed any person lying on the bare ground, so that I was very fortunate in having my “gadó” with me. A bedstead of some kind is a most necessary piece of furniture for an African traveller, as I have already remarked on a previous occasion; but it should be of a lighter description than my heavy boards, which, notwithstanding their thickness, were soon split, and at length smashed to pieces, in the thick forests through which we often had to pass. Our bivouac in the evening round our fire was exceedingly agreeable, the staid and grave demeanour of my burly and energetic companion imposing even upon the frivolous Mohammed, who at this time behaved much better than usual. Gajére informed me that the direct western road from here to Tasáwa passed by the[9] village Gárari, the pond Úrafa, the well Jíga, and by Birni-n-Tázin, while we were to follow an eastern road. Not far from our encampment, eastward, was a swamp named Tágelel.

Sunday, January 12th.Several camels were missing in the morning, as was indeed very natural in a country like this, thickly covered with trees and underwood. Soon, however, a tremendously shrill cry, passing from troop to troop, and producing altogether a most startling effect, announced that the animals had been found; and a most interesting and lively scene ensued, each party, scattered as the caravan was through the forest, beginning to load their camels on any narrow open space at hand. The sky was thickly overcast; and the sun did not break forth till after we had gone some three or four miles. We passed a beautiful tsámia, or tamarind-tree, which was, I think, the first full-grown tree of this species we had seen, those in Tágelel being mere dwarfs. Having descended a little, we passed at eleven o’clock a small hamlet or farming-village called Kauye-n-Sálakh; and I afterwards observed the first tulip-tree, splendidly covered with the beautiful flower just open in all the natural finery of its colours, while not a single leaf adorned the tree. I think this was the first tree of the kind we had passed on our road, although Overweg (whose attention I drew to it) asserted that he had seen specimens of it the day before; nevertheless I doubt their having escaped my observation, as I took the greatest interest in noting down accurately[10] where every new species of plant first appeared. At four o’clock in the afternoon we saw the first cotton-fields, which alternated with the corn-fields most agreeably. The former are certainly the greatest and most permanent ornament of any landscape in these regions, the plant being in leaf at almost every season of the year, and partly even in a state of fructification; but a field of full-grown cotton-plants, in good order, is very rarely met with in these countries, as they are left generally in a wild state, over-grown with all sorts of rank grass. A little beyond these fields we pitched our tent.

Monday, January 13th.We started at rather a late hour, our road being crossed by a number of small paths which led to watering-places; and we were soon surrounded by a great many women from a neighbouring village called Baíbay, offering for sale, to the people of the caravan, “godjía,” or ground-nuts, and “dákkwa,” a sort of dry paste made of pounded Guinea corn (Pennisetum), with dates and an enormous quantity of pepper. This is the meaning of dákkwa in these districts; it is, however, elsewhere used as a general term signifying only paste, and is often employed to denote a very palatable sort of sweatmeat made of pounded rice, butter, and honey. We then passed on our left the fields of the village, those near the road being well and carefully fenced, and lying around the well, where half the inhabitants of the place were assembled to draw water, which required no small pains, the depth of the well exceeding[11] twenty fathoms. Attempting to water the horse, I found that the water was excessively warm; unfortunately, I had not got my thermometer with me, but resolved to be more careful in future. On passing the village, we were struck by the neatness with which it was fenced on this side; and I afterwards learned by experience what a beautiful and comfortable dwelling may be arranged with no other material than reeds and corn-stalks. The population of these villages consists of a mixture of Mohammedans and pagans; but I think the majority of the inhabitants are Mohammedans.

After a short interval of woody country, we passed a village of the name of Chirák, with another busy scene round the well. In many districts in Central Africa the labour of drawing water, for a portion of the year, is so heavy that it occupies the greater part of the inhabitants half the day; but fortunately, at this season, with the exception of weaving a little cotton, they have no other employment, while during the season when agricultural labours are going on water is to be found everywhere, and the wells are not used at all. Búzawe are scattered everywhere hereabouts, and infuse into the population a good deal of Berber blood. Very pure Háusa is spoken.

It was near Chirák that Overweg, who had determined to go directly to Tasáwa, in order to commence his intended excursion to Góber and Marádi separated from me. This was indeed quite a gallant commencement[12] of his undertaking, as he had none of Ánnur’s people with him, and besides Ibrahím and the useful snake-like Amánkay (who had recovered from his guineaworm), his only companion was a Tébu who had long been settled in Ásben, and whom he had engaged for the length of his intended trip. At that time he had still the firm intention to go to Kúkawa by way of Kanó, and begged me to leave his things there. He was in excellent health, and full of an enthusiastic desire to devote himself to the study of the new world which opened before us; and we parted with a hearty wish for each other’s success in our different quarters before we were to meet again in the capital of Bórnu—for we did not then know that we should have an interview in Tasáwa.

I now went on alone, but felt not at all depressed by solitude, as I had been accustomed from my youth to wander about by myself among strange people. I felt disposed, indeed, to enter into a closer connection with my black friend Gajére, who was very communicative, but oftentimes rather rude, and unable to refrain from occasionally mocking the stranger who wanted to know everything, and would not acknowledge Mohammed in all his prophetic glory. He called my attention to several new kinds of trees while we were passing the two villages Bagángaré and Tangónda. These were the “baushi,” the “karámmia,” and the “gónda,” the last being identical with the Carica Papaya, and rather rare in the northern parts of Negroland, but very common in[13] the country between Kátsena and Núpe, and scattered in single specimens over all the country from Kanó and Gújeba southwards to the river Bénuwé; but at that time I was ignorant that it bore a splendid fruit, with which I first became acquainted in Kátsena. The whole country, indeed, had a most interesting and cheerful appearance, villages and cornfields succeeding each other with only short intervals of thick underwood, which contributed to give richer variety to the whole landscape, while the ground was undulating, and might sometimes even be called hilly. We met a numerous herd of fine cattle belonging to Gozenákko, returning to their pasture-grounds after having been watered,—the bulls all with the beautiful hump, and of fine strong limbs, but of moderate size, and with small horns. Scarcely had this moving picture passed before our eyes, when another interesting and characteristic procession succeeded—a long troop of men, all carrying on their heads large baskets filled with the fruit of the góreba (Cucifera, or Hyphaene Thebaïca), commonly called the gingerbread-tree, which, in many of the northern districts of Negroland, furnishes a most important article of food, and certainly seasons many dishes very pleasantly, as I shall have occasion to mention in the course of my narrative. Further on, the fields were enlivened with cattle grazing in the stubble, while a new species of tree, the “kírria,” attracted my attention.

Thus we reached Gozenákko; and while my servants[14] Mohammed and the Gatróni went with the camel to the camping-ground, I followed my sturdy overseer to the village in order to water the horse; for though I might have sent one of my men afterwards, I preferred taking this opportunity of seeing the interior of the village. It is of considerable size, and consists of a town and its suburbs, the former being surrounded with a “kéffi,” or close stockade of thick stems of trees, while the suburbs are ranged around without any inclosure or defence. All the houses consist of conical huts made entirely of stalks and reeds; and great numbers of little granaries were scattered among them. As it was about half-past two in the afternoon, the people were sunk in slumber or repose, and the well was left to our disposal; afterwards, however, we were obliged to pay for the water. We then joined the caravan, which had encamped at no great distance eastward of the village, in the stubble-fields. These, enlivened as they were by a number of tall fan-palms besides a variety of other trees, formed a very cheerful open ground for our little trading-party, which, preparing for a longer stay of two or three days, had chosen its ground in a more systematic way, each person arranging his “tákrufa,” or the straw sacks containing the salt, so as to form a barrier open only on one side, in the shape of an elongated horseshoe, in the recess of which they might stow away their slender stock of less bulky property, and sleep themselves, while in order to protect the salt from behind, a light[15] stockade of the stalks of Guinea corn was constructed on that side; for having now exchanged the regions of highway robbers and marauders for those of thieves, we had nothing more to fear from open attacks, but a great deal from furtive attempts by night.

Scarcely had our people made themselves comfortable, when their appetite was excited by a various assortment of the delicacies of the country, clamourously offered for sale by crowds of women from the village. The whole evening a discordant chime was rung upon the words “nóno” (sour milk), “may” (butter), “dodówa” (the vegetable-paste above mentioned), “kúka” (the young leaves of the Adansonia, which are used for making an infusion with which meat or the “túwo” is eaten), and “yáru da dária.” The last of these names, indeed, is one which characterizes and illustrates the cheerful disposition of the Háusa people; for the literal meaning of it is, “the laughing boy,” or “the boy to laugh,” while it signifies the sweet ground-nut, which if roasted is indeed one of the greatest delicacies of the country. Reasoning from subsequent experience, I thought it remarkable that no “túwo” (the common paste or hasty pudding made of millet, called “fufu” on the western coast), which forms the ordinary food of the natives, was offered for sale; but it must be borne in mind that the people of Ásben care very little about a warm supper, and like nothing better than the fura or ghussub-water, and the corn in its crude state,[16] only a little pounded. To this circumstance the Arabs generally attribute the enormous and disgusting quantity of lice with which the Kél-owí, even the very first men of the country, are covered.

I was greatly disappointed in not being able to procure a fowl for my supper. The breeding of fowls seems to be carried on to a very small extent in this village, although they are in such immense numbers in Damerghú, that a few years ago travellers could buy “a fowl for a needle.”

Tuesday, January 14th.Seeing that we should make some stay here, I had decided upon visiting the town of Tasáwa, which was only a few miles distant to the west, but deferred my visit till the morrow, in order to see the town in the more interesting phase of the “káswa-n-Láraba,” or the Wednesday market. However, our encampment, where I quietly spent the day, was itself changed into a lively and bustling market; and even during the heat of the day the discordant cries of the sellers did not cease.

My intelligent and jovial companion meanwhile gave me some valuable information with regard to the revenue of the wealthy governor of Tasáwa, who in certain respects is an independent prince, though he may be called a powerful vassal of the king or chief of Marádi. Every head of a family in his territory pays him three thousand kurdí, as “kurdí-n-kay” (head-money or poll-tax); besides, there is an ample list of penalties (“kurdí-n-laefi”), some of them very heavy: thus, for example, the fine for having[17] flogged another man, or most probably for having given him a sound cudgelling, is as much as ten thousand kurdí; for illicit paternity, one hundred thousand kurdí—an enormous sum considering the economic condition of the population, and which, I think, plainly proves how rarely such a thing happens in this region; but of course where every man may lawfully take as many wives as he is able to feed, there is little excuse for illicit intercourse. In case of wilful murder, the whole property of the murderer is forfeited, and is of right seized by the governor.

Each village has its own mayor, who decides petty matters, and is responsible for the tax payable within his jurisdiction. The king, or paramount chief, has the power of life and death; and there is no appeal from his sentence to the ruler of Marádi. However, he cannot venture to carry into effect any measure of consequence without asking the opinion of his privy council, or at least that of the ghaladíma or prime minister, some account of whose office I shall have an opportunity of giving in the course of my narrative. The little territory of Tasáwa might constitute a very happy state, if the inhabitants were left in quiet; but they are continually harassed by predatory expeditions, and even last evening, while we were encamped here, the Féllani drove away a small herd of ten calves from the neighbouring village of Kálgo.

About noon the “salt” of the serkí-n-Kél-owí arrived with the people of Olalówa, as well as that of Sálah Lúsu’s head man, who before had always been[18] in advance of us. In the evening I might have fancied myself a prince; for I had a splendid supper, consisting of a fowl or two, while a solitary maimólo cheered me with a performance on his simple three-stringed instrument, which, however monotonous, was still expressive of much feeling, and accompanied with a song in my praise.

Wednesday, January 15th.At the very dawn of day, to my great astonishment, I was called out of the tent by Mohammed, who told me that Fárraji, Lúsu’s man, our companion from Ghát, had suddenly arrived from Zínder with three or four Bórnu horsemen, and had express orders with regard to me. However, when I went out to salute him, he said nothing of his errand, but simply told me that he wanted first to speak to Elaíji, the chief of the caravan. I therefore went to the latter myself to know what was the matter, and learnt from the old man, that though he was not able to make out all the terms of the letters of which Fárraji was the bearer, one of which was written by the sheríf and the other by Lúsu, he yet understood that the horsemen had come with no other purpose but to take me and Overweg to Zínder, without consulting our wishes, and that the sheríf as well as Lúsu had instructed him to send us off in company with these fellows, but that they had also a letter for Ánnur, who ought to be consulted. As for himself, the old man (well aware of the real state of affairs, and that the averment of a letter having arrived from the consul at Tripoli, to the effect that till[19] further measures were taken with regard to our recent losses we ought to stay in Bórnu, was a mere sham and fabrication) declared that he would not force us to do anything against our inclination, but that we ought to decide ourselves what was best to be done.

Having, therefore, a double reason for going to Tasáwa, I set out as early as possible, accompanied by my faithless, wanton Tunisian shushán, and by my faithful, sedate Tageláli overseer. The path leading through the suburbs of Gozenákko was well fenced, in order to prevent any violation of property; but on the western side of the village there was scarcely any cultivated ground, and we soon entered upon a wilderness where the “dúmmia” and the “karása” were the principal plants, when, after a march of a little more than three miles, the wild thicket again gave way to cultivated fields, and the town of Tasáwa appeared in the distance—or rather (as is generally the case in these countries, where the dwellings are so low, and where almost all the trees round the towns are cut down, for stratagetical as well as economical reasons) the fine shady trees in the interior of the town were seen, which make it a very cheerful place. After two miles more we reached the suburbs, and, crossing them, kept along the outer ditch which runs round the stockade of the town, in order to reach Al Wáli’s house, under whose special protection I knew that Mr. Overweg had placed himself.

My friend’s quarters, into which we were shown, were very comfortable, although rather narrow. They[20] consisted of a courtyard, fenced with mats made of reeds, and containing a large shed or “runfá,” likewise built of mats and stalks, and a tolerably spacious hut, the walls built of clay (“bángo”), but with a thatched roof (“shíbki”). The inner part of it was guarded by a cross-wall from the prying of indiscreet eyes.

Overweg was not a little surprised on hearing the recent news; and we sent for El Wákhshi, our Ghadámsi friend from Tin-téggana, in order to consult him, as one who had long resided in these countries, and who, we had reason to hope, would be uninfluenced by personal considerations. He firmly pronounced his opinion that we ought not to go, and afterwards, when Fárráji called Mánzo and Al Wáli to his aid, entered into a violent dispute with these men, who advised us to go; but he went too far in supposing that the letter had been written with a malicious intention. For my part, I could well imagine that the step was authorized by the sheikh of Bórnu, or at least by his vizier, who might have heard long ago of our intention to go to Kanó, as it had been even Mr. Richardson’s intention to go there, which indeed he ought to have done in conformity with his written obligations to Mohammed e’ Sfáksi; they might therefore have instructed the sheríf to do what he might think fit to prevent us from carrying out our purpose. However, it seemed not improbable that Lúsu had something to do with the affair. But it was absolutely necessary for Mr.[21] Overweg and myself, or for one of us at least, to go to Kanó, as we had several debts to pay, and were obliged to sell the little merchandise we had with us, in order to settle our affairs.

We were still considering the question, when we were informed that our old protector the chief Ánnur had just arrived from Zínder; and I immediately determined to go to see him in his own domain at Náchira, situated at a little more than a mile N.E. from Tasáwa. In passing through the town I crossed the market-place, which at that time, during the hot hours of the day, was very well frequented, and presented a busy scene of the highest interest to a traveller emerging from the desert, and to which the faint sparks of life still to be observed in Ágades cannot be compared. A considerable number of cattle were offered for sale, as well as six camels, and the whole market was surrounded by continuous rows of runfás or sheds; but provisions and ready-dressed food formed the staple commodity, and scarcely anything of value was to be seen. On leaving the town I entered an open country covered with stubble-fields, and soon reached that group of Náchira where the chief had fixed his quarters. In front of the yard was a most splendid tamarind-tree, such as I had not yet seen. Leaving my horse in its shade, I entered the yard, accompanied by Gajére, and looked about for some time for the great man, when at length we discovered him under a small shed or runfá of a conical form, so low that we had passed it without noticing[22] the people collected in its shade. There he lay surrounded by his attendants, as was his custom in general when reposing in the day-time, with no clothing but his trowsers, while his shirt, rolled up, formed a pillow to rest his left arm upon. He did not seem to be in the best humour—at least he did not say a single cheerful word to me; and though it was the very hottest time of the day, he did not offer me as much as a draught of water. I had expected to be treated to a bowl of well-soaked “fura” seasoned with cheese. But what astonished me more than his miserly conduct (which was rather familiar to me) was, that I learned from his own mouth that he had not been to Zínder at all, whither we had been assured he had accompanied Mr. Richardson, but that he had spent all the time in Tágelel, from which place he had now come direct. I was therefore the more certain that Lúsu had some part in the intrigues. Ánnur, who had not yet received the letter addressed to him from Zínder, knew nothing about it, and merely expressed his surprise that such a letter had been written, without adding another word.

Seeing the old chief in a very cheerless humour, I soon left him, and took a ramble with Gajére over the place. The estate is very extensive, and consists of a great many clusters of huts scattered over the fields, while isolated dúm-palms give to the whole a peculiar feature. The people, all followers and mostly domestic slaves of Ánnur, seemed to live in[23] tolerable ease and comfort, as far as I was able to see, my companion introducing me into several huts. Indeed every candid person, however opposed to slavery he may be, must acknowledge that the Tawárek in general, and particularly the Kél-owí, treat their slaves not only humanely, but even with the utmost indulgence and affability, and scarcely let them feel their bondage at all. Of course there are exceptions, as the cruelty of yoking slaves to a plough, and driving them on with a whip (which I had witnessed in Aúderas), is scarcely surpassed in any of the Christian slave-states; but these exceptions are extremely rare.

When I returned from my ramble, Mr. Overweg had also arrived, and the old chief had received the letter; and though neither he nor any of his people could read it, he was fully aware of its contents, and disapproved of it entirely, saying that we should act freely, and according to the best of our knowledge. I then returned with my countryman into the town, and remained some time with him. In front of his dwelling was encamped the natron-caravan of Al Wáli, which in a few days was to leave for Núpe or (as the Háusa people say) Nýffi. We shall have to notice very frequently this important commerce, which is carried on between the shores of the Tsád and Nýffi.

I left the town at about five o’clock, and feeling rather hungry on reaching the encampment in Gozenákko, to the great amusement of our neighbours,[24] parodying the usual salute of “iná labári” (what is the news)? I asked my people immediately the news of our cooking-pot, “iná labári-n-tokónia” (what news of the pot)? I was greatly pleased with my day’s excursion; for Tasáwa was the first large place of Negroland proper which I had seen, and it made the most cheerful impression upon me, as manifesting everywhere the unmistakable marks of the comfortable, pleasant sort of life led by the natives:—the courtyard fenced with a “dérne” of tall reeds, excluding to a certain degree the eyes of the passer-by, without securing to the interior absolute secrecy; then near the entrance the cool shady place of the “runfá” for ordinary business and for the reception of strangers, and the “gída,” partly consisting entirely of reed (“dáki-n-kára”) of the best wickerwork, partly built of clay in its lower parts (“bóngo”), while the roof consists of reeds only (“shíbki”)—but of whatever material it may consist, it is warm and well adapted for domestic privacy,—the whole dwelling shaded with spreading trees, and enlivened with groups of children, goats, fowls, pigeons, and, where a little wealth had been accumulated, a horse or a pack-ox.

With this character of the dwellings, that of the inhabitants themselves is in entire harmony, its most constant element being a cheerful temperament, bent upon enjoying life, rather given to women, dance, and song, but without any disgusting excess. Everybody here finds his greatest happiness in a comely lass;[25] and as soon as he makes a little profit, he adds a young wife to his elder companion in life: yet a man has rarely more than two wives at a time. Drinking fermented liquor cannot be strictly reckoned a sin in a place where a great many of the inhabitants are pagans; but a drunken person, nevertheless, is scarcely ever seen: those who are not Mohammedans only indulge in their “gíya,” made of sorghum, just enough to make them merry and enjoy life with more light-heartedness. There was at that time a renegade Jew in the place, called Músa, who made spirits of dates and tamarinds for his own use. Their dress is very simple, consisting, for the man, of a wide shirt and trowsers, mostly of a dark colour, while the head is generally covered with a light cap of cotton cloth, which is negligently worn, in all sorts of fashions. Others wear a rather closely fitting cap of green cloth, called báki-n-záki. Only the wealthier amongst them can afford the “zénne” or shawl, thrown over the shoulder like the plaid of the Highlanders. On their feet the richer class wear very neat sandals, such as we shall describe among the manufactures of Kanó.

As for the women, their dress consists almost entirely of a large cotton cloth, also of dark colour—“the túrkedi,” fastened under or above the breast—the only ornament of the latter in general consisting of some strings of glass beads worn round the neck. The women are tolerably handsome, and have pleasant features; but they are worn out by excessive[26] domestic labour, and their growth never attains full and vigorous proportions. They do not bestow so much care upon their hair as the Féllani, or some of the Bagírmi people.

There are in the town a good many “Búzawe,” or Tawárek half-castes, who distinguish themselves in their dress principally by the “ráwani” or tesílgemíst (the lithám) of white or black colour, which they wind round their head in the same way as the Kél-owí; but their mode of managing the tuft of hair left on the top of the head is not always the same, some wearing their curled hair all over the crown of the head, while others leave only a long tuft, which was the old fashion of the Zenágha. The pagan inhabitants of this district wear, in general, only a leathern apron (“wuélki”); but with the exception of young children, none are seen here quite naked. The town was so busy, and seemed so well inhabited, that on the spot I estimated its population at fifteen thousand; but this estimate is probably too high.

Thursday, January 16th.We still remained near Gozenákko, and I was busy studying Temáshight, after which I once more went over the letter of the sheríf El Fási, Háj Beshír’s agent in Zínder; and having become fully aware of the dictatorial manner in which he had requested Elaíji to forward me and Mr. Overweg to him (just as a piece of merchandise) without asking our consent, I sat down to write him a suitable answer, assuring him that, as I was desirous[27] of paying my respects to the son of Mohammed el Kánemi and his enlightened vizier, I would set out for their residence as soon as I had settled my affairs in Kanó, and that I was sure of attaining my ends without his intervention, as I had not the least desire to visit him.

This letter, as subsequent events proved, grew into importance, for the sheríf being perplexed by its tone, sent it straight on to Kúkawa, where it served to introduce me at once to the sheikh and his vizier. But the difficulty was to send it off with the warlike messengers who had brought the sheríf’s letters, as they would not go without us, and swore that their orders, from the sheríf as well as from Serk’ Ibrám, were so peremptory that they should be utterly disgraced if they returned empty-handed. At length, after a violent dispute with Fárráji and these warlike-looking horsemen, the old chief, who took my part very fairly, finished the matter by plainly stating that if we ourselves, of our own free will, wanted to go, we might do so, but if we did not wish to go, instead of forcing us, he would defend us against anybody who should dare to offer us violence. Nevertheless the messengers would not depart; and it seemed impossible to get rid of them till I made each of them a present of two mithkáls, when they mounted their horses with a very bad grace, and went off with my letter. The energetic and straightforward but penurious old chief left us in the afternoon, and rode to Kálgo, a village at no great distance.

[28]Friday, January 17th.Still another day of halt, in order, as I was told, to allow Háj ʿAbdúwa’s salt-caravan to come up and join us. Being tired of the camp, I once more went into the town to spend my day usefully and pleasantly; leaving all my people behind, I was accompanied by some of my fellow-travellers of the caravan. Arriving at Overweg’s quarters, what was my surprise to find Fárráji not yet gone, but endeavouring to persuade my companion, with all the arts of his barbarous eloquence, that though I should not go, he at least might, in which case he would be amply rewarded with the many fine things which had been prepared in Zínder for our reception. The poor fellow was greatly cast down when he saw me, and soon made off in very bad humour, while I went with Overweg to El Wákhshi, who was just occupied in that most tedious of all commercial transactions in these countries, namely, the counting of shells; for in all these inland countries of Central Africa the cowries or kurdí (Cypræa moneta) are not, as is customary in some regions near the coast, fastened together in strings of one hundred each, but are separate, and must be counted one by one. Even those “tákrufa” (or sacks made of rushes) containing 20,000 kurdí each, as the governors of the towns are in the habit of packing them up, no private individual will receive without counting them out. The general custom in so doing is to count them by fives, in which operation some are very expert, and then, according to the amount of the sum, to form heaps of[29] two hundred (or ten háwiyas[2]) or a thousand each. Having at length succeeded, with the help of some five or six other people, in the really heroic work of counting 500,000 shells, our friend went with us to the sick sultan Mazáwaji: I say sultan, as it is well for a traveller to employ these sounding titles of petty chiefs, which have become naturalized in the country from very ancient times, although it is very likely that foreign governments would be unwilling to acknowledge them. The poor fellow, who was living in a hut built half of mud, half of reeds, was suffering under a dreadful attack of dysentery, and looked like a spectre; fortunately my friend succeeded in bringing on perspiration with some hot tea and a good dose of peppermint, in the absence of stronger medicines. We then went to the house of Amánkay, that useful fellow so often mentioned in the Journal of the late Mr. Richardson, and by myself. He was a “búzu” of this place, and had many relatives here, all living near him. His house was built in the general style; but the interior of the courtyard was screened from profane eyes. Fortunately I had taken with me some small things, such as mirrors, English darning-needles, and some knives, so that I was able to give a small present to each of his kinsmen and relatives, while he treated us with a calabash of fura.

[30]In the afternoon we strolled a long time about the market, which not being so crowded as the day before yesterday, was on that account far more favourable for observation. Here I first saw and tasted the bread made of the fruit of the magariá-tree, and called “túwo-n-magariá,” which I have mentioned before, and was not a little astonished to see whole calabashes filled with roasted locusts (“fará”), which occasionally form a considerable part of the food of the natives, particularly if their grain has been destroyed by this plague, as they can then enjoy not only the agreeable flavour of the dish, but also take a pleasant revenge on the ravagers of their fields. Every open space in the midst of the market-place was occupied by a fire-place (“maidéffa”) on a raised platform, on which diminutive morsels of meat, attached to a small stick, were roasting, or rather stewing, in such a way that the fat, trickling down from the richer pieces attached to the top of the stick, basted the lower ones. These dainty bits were sold for a single shell or “urí”[3] each. I was much pleased at recognizing the red cloth which had been stolen from my bales in the valley of Afís, and which was exposed here for sale. But the most interesting thing in the town was the “máriná” (the dyeing-place) near the wall, consisting of a raised platform of clay with fourteen holes or pits, in which the[31] mixture of indigo is prepared, and the cloths remain for a certain length of time, from one to seven days, according to the colour which they are to attain. It is principally this dyeing, I think, which gives to many parts of Negroland a certain tincture of civilization, a civilization which it would be highly interesting to trace, if it were possible, through all the stages of its development.

While rambling about, Overweg and I for a while were greatly annoyed by a tall fellow, very respectably and most picturesquely dressed, who professed himself to be a messenger from the governor of Kátsena, sent to offer us his compliments and to invite us to go to him. Though the thing was not altogether impossible, it looked rather improbable; and having thanked him profusely for his civility, we at length succeeded in getting rid of him. In the evening I returned to our camping-ground with Ídder the Emgédesi man mentioned in a preceding part of my narrative, and was very glad to receive reliable information that we were to start the following day.

[1]This same variation is to be observed in the name Marádi, which many people pronounce Mariyádi.

[2]“Háwiya” means twenty, and seems originally to have been the highest sum reached by the indigenous arithmetic. I shall say more about this point in my vocabulary of the Háusa language.

[3]“Kurdí” (shells) is the irregular plural of “urí” (a single shell).

[32]CHAP. XXIII.

GAZÁWA. — RESIDENCE IN KÁTSENA.

Saturday, January 18th.We made a good start with our camels, which having been treated to a considerable allowance of salt on the first day of our halt, had made the best possible use of these four days’ rest to recruit their strength. At the considerable village of Kálgo, which we passed at a little less than five miles beyond our encampment, the country became rather hilly, but only for a short distance. Tamarinds constituted the greatest ornament of the landscape. A solitary traveller attracted our notice on account of his odd attire, mounted as he was on a bullock with three large pitchers on each side. Four miles beyond Kálgo the character of the country became suddenly changed, and dense groups of dúm-palms covered the ground. But what pleased me more than the sight of these slender forked trees was when, half an hour after mid-day, I recognized my splendid old friend the bóre-tree, of the valley Bóghel[4],[33] which had excited my surprise in so high a degree, and the magnificence of which at its first appearance was not at all eclipsed by this second specimen in the fertile regions of Negroland. Soon afterwards we reached the fáddama of Gazáwa; and leaving the town on our right hidden in the thick forest, we encamped a little further on in an open place, which was soon crowded with hucksters and retailers. I was also pestered with a visit from some half-caste Arabs settled in the town; but fortunately, seeing that they were likely to wait in vain for a present, they went off, and were soon succeeded by a native mʿallem from the town, whose visit was most agreeable to me.

About sunset the “serkí-n-turáwa,” or consul of the Arabs, came to pay his regards to Elaíji, and introduced the subject of a present, which, as he conceived, I ought to make to the governor of the town as a sort of passage-money; my protector, however, would not listen to the proposal, but merely satisfied his visitor’s curiosity by calling me into his presence and introducing him to me. The serkí was very showily and picturesquely dressed—in a green and white striped tobe, wide trowsers of a speckled pattern and colour, like the plumage of the Guinea fowl, with an embroidery of green silk in front of the legs. Over this he wore a gaudy red bernús, while round his red cap a red and white turban was wound crosswise in a very neat and careful manner. His sword was slung over his right shoulder by means of thick hangers[34] of red silk ornamented with enormous tassels. He was mounted on a splendid charger, the head and neck of which was most fancifully ornamented with a profusion of tassels, bells, and little leather pockets containing charms, while from under the saddle a shabrack peeped out, consisting of little triangular patches in all the colours of the rainbow.

This little African dandy received me with a profusion of the finest compliments, pronounced with the most refined and sweet accent of which the Háusa language is capable. When he was gone, my old friend Elaíji informed me that he had prevented the “consul of the Arabs” from exacting a present from me, and begged me to acknowledge his service by a cup of coffee, which of course I granted him with all my heart. Poor old Elaíji! He died in the year 1854, in the forest between Gazáwa and Kátsena, where from the weakness of age he lost his way when left alone. He has left on my memory an image which I shall always recall with pleasure. He was certainly the most honourable and religious man among the Kél-owí.

The market in our encampment, which continued till nightfall, reached its highest pitch at sunset, when the people of the town brought ready-made “túwo,” each dish, with rather a small allowance, selling for three kurdí, or not quite the fourth part of a farthing. I, however, was happy in not being thrown upon this three-kurdí supper; and while I indulged in my own home-made dish, Gajére entertained me with the[35] narrative of a nine days’ siege, which the warlike inhabitants of Gazáwa had sustained, ten years previously, against the whole army of the famous Bello.

Sunday, January 19th.We remained encamped; and my day was most agreeably and usefully spent in gathering information with regard to the regions which I had just entered. There was first Maʿadi, the slave of Ánnur, a native of Bórnu, who when young had been made prisoner by the Búdduma of the lake, and had resided three years among these interesting people, till having fallen into the hands of the Welád Slimán, then in Kánem, he at length, on the occasion of the great expedition of the preceding year, had fallen into the power of the Kél-owí. Although he owed the loss of his liberty to the freebooting islanders, he was nevertheless a great admirer of theirs, and a sincere vindicator of their character. He represented them as a brave and high-spirited people, who made glorious and successful inroads upon the inhabitants of the shores of the lake with surprising celerity, while at home they were a pious and God-fearing race, and knew neither theft nor fraud among themselves. He concluded his eloquent eulogy of this valorous nation of pirates by expressing his fervent hope that they might for ever preserve their independence against the ruler of Bórnu.

I then wrote, from the mouth of Gajére and Yáhia (another of my friends), a list of the places lying round about Gazáwa, as follows:—On the east side, Mádobí,[36] Maíjirgí[5], Kógena na kay-debú, Kórmasa, Kórgom, Kánche (a little independent principality); Gumdá, half a day east of Gazáwa, with numbers of Ásbenáwa; Démbeda, or Dúmbida, at less distance; Shabáli, Babíl, Túrmeni, Gínga, Kandémka, Sabó-n-kefí, Zángoni-n-ákwa, Kúrni, Kurnáwa, Dángudaw. On the west side, where the country is more exposed to the inroads of the Fúlbe or Féllani, there is only one place of importance, called Tindúkku, which name seems to imply a close relation to the Tawárek. All these towns and villages are said to be in a certain degree dependent on Raffa, the “babá” (i.e. great man or chief) of Gazáwa, who, however, himself owes allegiance to the supreme ruler of Marádi.

There was an exciting stir in the encampment at about ten o’clock in the morning, illustrative of the restless struggle going on in these regions. A troop of about forty horsemen, mostly well mounted, led on by the serkí-n-Gumdá, and followed by a body of tall slender archers, quite naked but for their leathern aprons, passed through the different rows of the aïri, on their way to join the expedition which the prince of Marádi was preparing against the Féllani.

About noon the natron-caravan of Háj Al Wáli, which I had seen in Tasáwa, came marching up in[37] solemn order, led on by two drums, and affording a pleasant specimen of the character of the Háusa people. Afterwards I went into the town, which was distant from my tent about half a mile. Being much exposed to attacks from the Mohammedans, as the southernmost pagan place belonging to the Marádi-Góber union, Gazáwa has no open suburbs outside its strong stockade, which is surrounded by a deep ditch. It forms almost a regular quadrangle, having a gate on each side built of clay, which gives to the whole fortification a more regular character, besides the greater strength which the place derives from this precaution. Each gateway is twelve feet deep, and furnished on its top with a rampart sufficiently capacious for about a dozen archers. The interior of the town is almost of the same character as Tasáwa; but Gazáwa is rather more closely built, though I doubt whether its circumference exceeds that of the former place. The market is held every day, but, as might be supposed, is far inferior to that of Tasáwa, which is a sort of little entrepôt for the merchants coming from the north, and affords much more security than Gazáwa, which, though an important place with regard to the struggle carried on between Paganism and Islamism in these quarters, is not so with respect to commerce. The principal things offered for sale were cattle, meat, vegetables of different kinds, and earthenware pots. Gazáwa has also a máriná or dyeing-place, but of less extent than that of Tasáwa, as most of its inhabitants are[38] pagans, and wear no clothing but the leathern apron. Their character appeared to me to be far more grave than that of the inhabitants of Tasáwa; and this is a natural consequence of the precarious position in which they are placed, as well as of their more warlike disposition. The whole population is certainly not less than ten thousand.

Having visited the market, I went to the house of the mʿallem, where I found several Ásbenáwa belonging to our caravan enjoying themselves in a very simple manner, eating the fruits of the kaña, which are a little larger than cherries, but not so soft and succulent. The mʿallem, as I had an opportunity of learning on this occasion, is a protégé of Elaíji, to whom the house belongs. Returning with my companions to our encampment, I witnessed a very interesting sort of dance, or rather gymnastic play, performed on a large scale by the Kél-owí, who being arranged in long rows, in pairs, and keeping up a regular motion, pushed along several of their number under their arms—not very unlike some of our old dances.

Monday, January 20th.Starting early in the morning, we felt the cold very sensibly, the thermometer standing at 48° Fahr. a little before sunset. Cultivated fields interrupted from time to time the underwood for the first three miles, while the “ngílle,” or “kába,” formed the most characteristic feature of the landscape; but dúm-palms, at first very rarely seen, soon became prevalent, and continued[39] for the next two miles. Then the country became more open, while in the distance to the left extended a low range of hills. New species of trees appeared, which I had not seen before, as the “kókia,” a tree with large leaves of a dark-green colour, with a green fruit of the size of an apple, but not eatable. The first solitary specimens of the gigiña or deléb-palm, which is one of the most characteristic trees of the more southern regions, were also met with.

Moving silently along, about noon we met a considerable caravan, with a great number of oxen and asses led by two horsemen, and protected in the rear by a strong guard of archers; for this is one of the most dangerous routes in all Central Africa, where every year a great many parties are plundered by marauders, no one being responsible for the security of this disputed territory. We had here a thick forest on our left enlivened by numbers of birds; then about two o’clock in the afternoon we entered a fine undulating country covered with a profusion of herbage, while the large gámshi-tree, with its broad fleshy leaves of the finest green, formed the most remarkable object of the vegetable kingdom. All this country was once a bustling scene of life, with numbers of towns and villages, till, at the very commencement of this century, the “Jihádi,” or Reformer, rose among the Fúlbe of Góber, and, inflaming them with fanatic zeal, urged them on to merciless warfare against pagans as well as Mohammedans.

It was here that my companions drew my attention[40] to the tracks of the elephant, of whose existence in the more northern regions we had not hitherto seen the slightest trace—so that this seems to be the limit of its haunts on this side; and it was shortly afterwards that Gajére descried in the distance a living specimen making slowly off to the east; but my sight was not strong enough to distinguish it. Thus we entered the thicker part of the forest, and about half-past four in the afternoon reached the site of the large town of Dánkama, whither Mágajin Háddedu, the king of Kátsena, had retired after his residence had been taken by the Fúlbe, and from whence he waged unrelenting but unsuccessful war against the bloody-minded enemies of the religious as well as political independence of his country. Once, indeed, the Fúlbe were driven out of Kátsena; but they soon returned with renewed zeal and with a fresh army, and the Háusa prince was expelled from his ancient capital for ever. After several battles Dánkama, whither all the nobility and wealth of Kátsena had retired, was taken, ransacked, and burnt.

A solitary colossal kúka[6] (baobab), representing in its huge, leafless, and gloomy frame the sad recollections connected with the spot, shoots out from the prickly underwood which thickly overgrows the locality[7],[41] and points out the market-place once teeming with life. It was a most affecting moment; for, as if afraid of the evil spirits dwelling in this wild and deserted spot, all the people of the caravan, while we were thronging along the narrow paths opening between the thick prickly underwood, shouted with wild cries, cursing and execrating the Féllani, the authors of so much mischief, all the drums were beating, and every one pushed on in order to get out of this melancholy neighbourhood as soon as possible.

Having passed a little after sunset a large granitic mass projecting from the ground, called Korremátse, and once a place of worship, we saw in the distance in front the fires of those parties of the aïri which had preceded us; and greeting them with a wild cry, we encamped on the uneven ground in great disorder, as it had become quite dark. After a long march I felt very glad when the tent was at length pitched. While the fire was lighted, and the supper preparing, Gajére informed me that, besides Dánkama, Bello destroyed also the towns of Jankúki and Madáwa in this district, which now presents such a frightful wilderness.[8]

[42]In the course of the night, the roar of a lion was heard close by our encampment.

Tuesday, January 21st.We started, with general enthusiasm, at an early hour; and the people of our troop seeing the fires of the other divisions of the salt-caravan in front of us still burning, jeered at their laziness, till at length, on approaching within a short distance of the fires, we found that the other people had set out long before, leaving their fires burning. A poor woman, carrying a load on her head, and leading a pair of goats, had attached herself to our party in Gazáwa; and though she had lost her goats in the bustle of the previous afternoon, she continued her journey cheerfully and with resignation.

After five hours’ march the whole caravan was suddenly brought to a stand for some time, the cause of which was a ditch of considerable magnitude, dug right across the path, and leaving only a narrow passage, the beginning of a small path which wound along through thick thorny underwood. This, together with the ditch, formed a sort of outer defence for the cultivated fields and the pasture-grounds of Kátsena, against any sudden inroad. Having passed[43] another projecting mass of granite rock, we passed two small villages on our left, called Túlla and Takumáku, from whence the inhabitants came out to salute us. We encamped at length in a large stubble-field, beyond some kitchen-gardens, where pumpkins (dúmma) were planted, two miles N.E. from the town of Kátsena. While we were pitching my tent, which was the only one in the whole encampment, the sultan or governor of Kátsena came out with a numerous retinue of horsemen, all well-dressed and mounted; and having learnt from Elaíji that I was a Christian traveller belonging to a mission (a fact, however, which he knew long before), he sent me soon afterwards a ram and two large calabashes or dúmmas filled with honey—an honour which was rather disagreeable to me than otherwise, as it placed me under the necessity of making the governor a considerable present in return. I had no article of value with me; and I began to feel some unpleasant foreboding of future difficulties.

An approximative estimate of the entire number of the salt-caravan, as affording the means of accurately determining the amount of a great national commerce carried on between widely-separated countries, had much occupied my attention, and having in vain tried on the road to arrive at such an estimate, I did all I could to-day to obtain a list of the different divisions composing it; but although Yáhia, one of the principal of Ánnur’s people, assured me that there were more than thirty troops, I was not[44] able to obtain particulars of more than the following: viz., encamped on this same ground with us was the salt-caravan of Ánnur, of Elaíji, of Hámma with the Kél-táfidet, of Sálah, of Háj Makhmúd with the Kél-tagrímmat, of Ámaki with the Amákita, of the Imasághlar (led by Mohammed dan Ággeg), of the Kél-azanéres, of the Kél-ínger (the people of Zingína), of the Kél-ágwau, and finally that of the Kél-chémia. No doubt none of these divisions had more than two hundred camels laden with salt, exclusive of the young and the spare camels; the whole of the salt, therefore, collected here at the time was at the utmost worth one hundred millions of kurdí, or about eight thousand pounds sterling. Beside the divisions of the aïri which I have just enumerated as encamped on this spot, the Erázar were still behind, while the following divisions had gone on in advance: the Kél-n-Néggaru; the Iseráraran, with the chief Bárka and the támberi (war chieftain) Nasóma; and the Ikázkezan, with the chiefs Mohammed Irólagh and Wuentúsa.

We may therefore not be far from the truth if we estimate the whole number of the salt-caravan of the Kél-owí, of this year, at two thousand five hundred camels. To this must be added the salt which had gone to Zínder, and which I estimate at about a thousand camel-loads, and that which had been left in Tasáwa for the supply of the markets of the country as far as Góber, which I estimate at from two hundred to three hundred camel-loads. But it must be[45] borne in mind that the country of Ásben had been for some time in a more than ordinarily turbulent state, and that consequently the caravan was at this juncture probably less numerous than it would be in quiet times.

Being rather uneasy with regard to the intention of the governor of the province, I went early the next morning to Elaíji, and assured him that, besides some small things, such as razors, cloves, and frankincense, I possessed only two red caps to give to the governor, and that I could not afford to contract more debts by buying a bernús. The good old man was himself aware of the governor’s intention, who, he told me, had made up his mind to get a large present from me, otherwise he would not allow me to continue my journey. I wanted to visit the town, but was prevented from doing so under these circumstances, and therefore remained in the encampment.