Large-size versions of illustrations are available by clicking on them.

General table of contents — Narrative in Index — Itineraries in Index

TRAVELS

AND DISCOVERIES

IN

NORTH

AND CENTRAL

AFRICA:

BEING A

JOURNAL OF AN EXPEDITION

UNDERTAKEN

UNDER THE AUSPICES OF H.B.M.’S

GOVERNMENT,

IN THE YEARS

1849-1855.

BY

HENRY BARTH, Ph.D., D.C.L.

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL AND ASIATIC

SOCIETIES,

&c. &c.

IN FIVE VOLUMES.

VOL. III.

LONDON:

LONGMAN, BROWN, GREEN, LONGMANS, & ROBERTS.

1857.

The right of translation is reserved.

London:

Printed by Spottiswoode & Co.

New-street Square.

[iii]CONTENTS

OF

THE THIRD VOLUME.

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| Page | |

| Rainy Season in Kúkawa | 1 |

| Supplies. — The Herbage. — Tropical Rains. — Mr. Vogel’s Statement. — The Winged Ant. — Various Kinds of Cultivation. — Intended Excursion to Kánem. — Mr. Overweg’s Memoranda. — Political Situation of Bórnu. — The Turks in Central Africa. — Sókoto and Wádáy. — The Festival. — Ceremonies of Festivity. — Dependent Situation. — My Horse. | |

| CHAP. XXXIX. | |

| Expedition to Kánem | 23 |

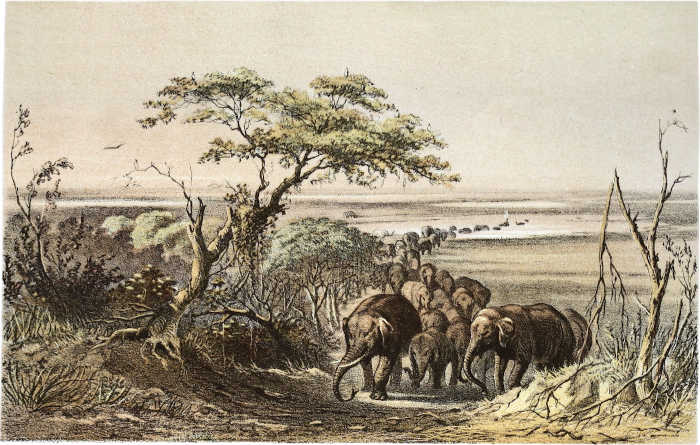

| Money-matters settled. — A Repentant Servant. — Delights of Open Encampment. — Dawerghú. — Treatment by Slaves. — Variety of Trees. — Scarcity of Water. — The Town of Yó. — Marriage Customs. — Character of the Country. — Arrival of Mr. Overweg. — Banks of the River. — Character of our Freebooting Companions. — Crossing the River. — Town of Báruwa. — View of the Tsád. — Native Salt. — Desolate Country. — Ninety-six Elephants. — Another Scene of Plunder. — Arrival at Berí. — Importance of Berí. — Fresh-water Lakes and Natron. — Submerged in a Bog. — A Large Snake. — The Valleys and Vales of Kánem. — Arrival at the Arab Camp. | |

| [iv]CHAP. XL. | |

| The Horde of the Welád Slimán | 61 |

| The Welád Slimán. — Their Power. — Slaughter of the Welád Slimán. — Interview with Sheikh Ghét. — Interview with ʿOmár. — Specimen of Predatory Life. — Runaway Female Slave. — Rich Vales. — Large Desertion. — A Jewish Adventurer. — Musical Box. — False Alarm. | |

| CHAP. XLI. | |

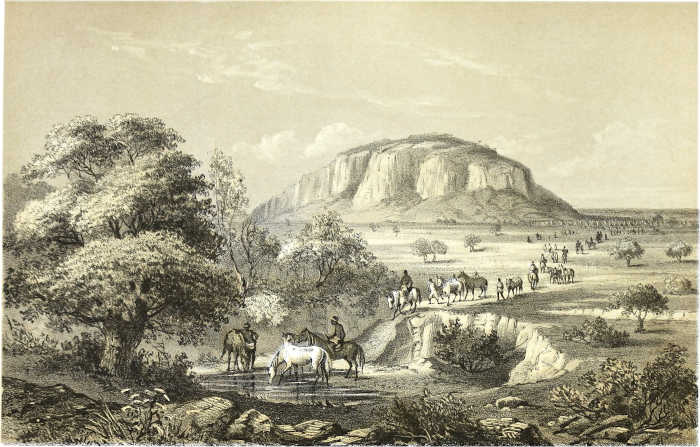

| Shitáti. — The Eastern, more favoured, Valleys of Kánem | 81 |

| Bír el Ftáim. — The Fugábú. — Projects frustrated. — Kárká and the Keghámma. — Elephant’s Track. — Bóro. — Bérendé. — Towáder. — Beautiful Vale. — Preparations for Attack. — Left behind. — Regularly-formed Valley. — Hénderi Síggesí. — Attack by the Natives. — Much Anxiety. — Join our Friends. — Encampment at Áláli Ádia. — Visited by the Keghámma. — Camp taken. — Restless Night. — Fine Vale Tákulum. — Vales of Shitáti. — Return to the principal Camp. — Wádáy Horsemen. — Set out on return to Kúkawa. — Departure from Kánem. — Alarms. — The Komádugu again. — Return to Kúkawa. | |

| CHAP. XLII. | |

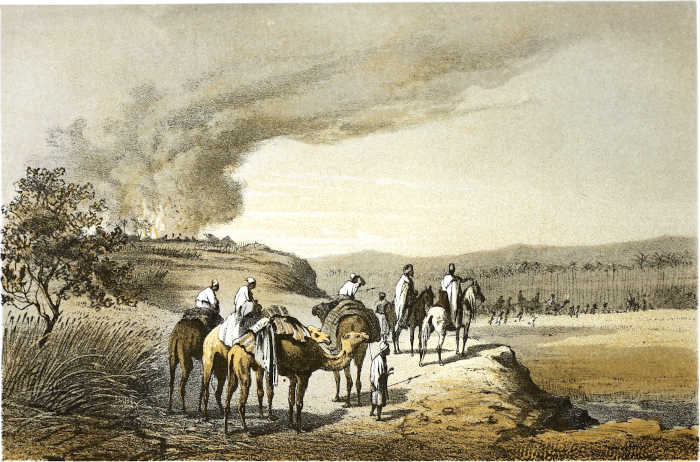

| Warlike Preparations against Mándará | 118 |

| Set out on another Expedition. — The Camp, or Ngáufate. — The Chef de Police Lamíno. — Army in motion. — Lamíno again. — Major Denham’s Adventure. — The Town of Márte. — Ála. — Encampment at Díkowa. — Firearms and Civilization. — Slavery and Slave-trade. — The Shúwa. — The Interior of Díkowa. — Industry. — Banks of the Yálowe. — Cotton Plantations. — The Camp Market. — Friendly Services. — Important Information. — Háj Edrís. | |

| CHAP. XLIII. | |

| The Border-region of the Shúwa | 149 |

| News from Mándará. — Áfagé. — Thieves forced to Fight. — The Sweet Sorghum. — Variations of Temperature. — Shallow Watercourses. — Subjection of Mándará. — Extensive Rice-fields. — Hard Ground. — Elephants. — The Court of Ádishén. — The Army on the March. — The Súmmoli. — The Army badly off. — Entering the Músgu Country. — Industry pillaged. — Native Architecture. — Affinity of the Músgu. — Their chief Places. — The Adventurous Chieftain. — Ádishén. — Christmas Events. | |

| [v]CHAP. XLIV. | |

| The Country of the Shallow Rivers. — Water-parting between the Rivers Bénuwé and Shárí | 186 |

| The Deléb-palm. — New Features. — Worship of Ancestors. — Cut off from the Army. — Spoil and Slaughter. — Alarm and Cowardice. — Músgu Weapons. — The Túburi not attacked. — Ngáljam of Démmo. — Destruction. — New Year. — Pagan Chiefs and Priests. — Fine Landscape. — The River of Logón. — Singular Water-combat. — The Túburi and their Lake. — The Swampy Character of the Ngáljam. — The River again. — Water-communication. — Plucky Pagans. — Balls and Stones. — Consequences of Slave-hunts. — Penetrating Southward. | |

| CHAP. XLV. | |

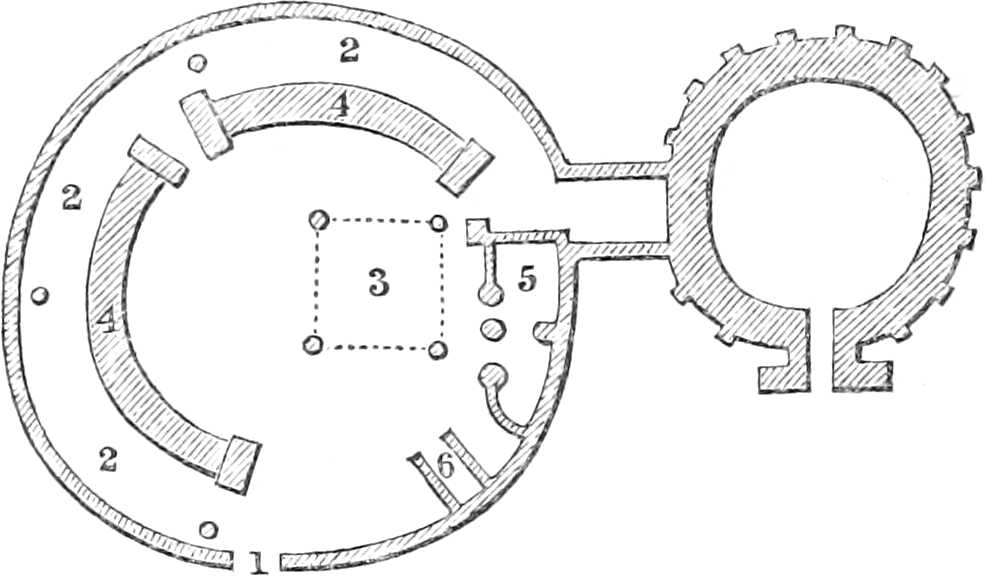

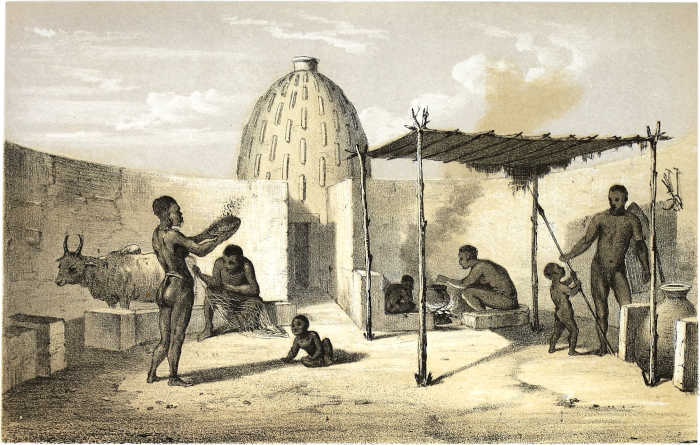

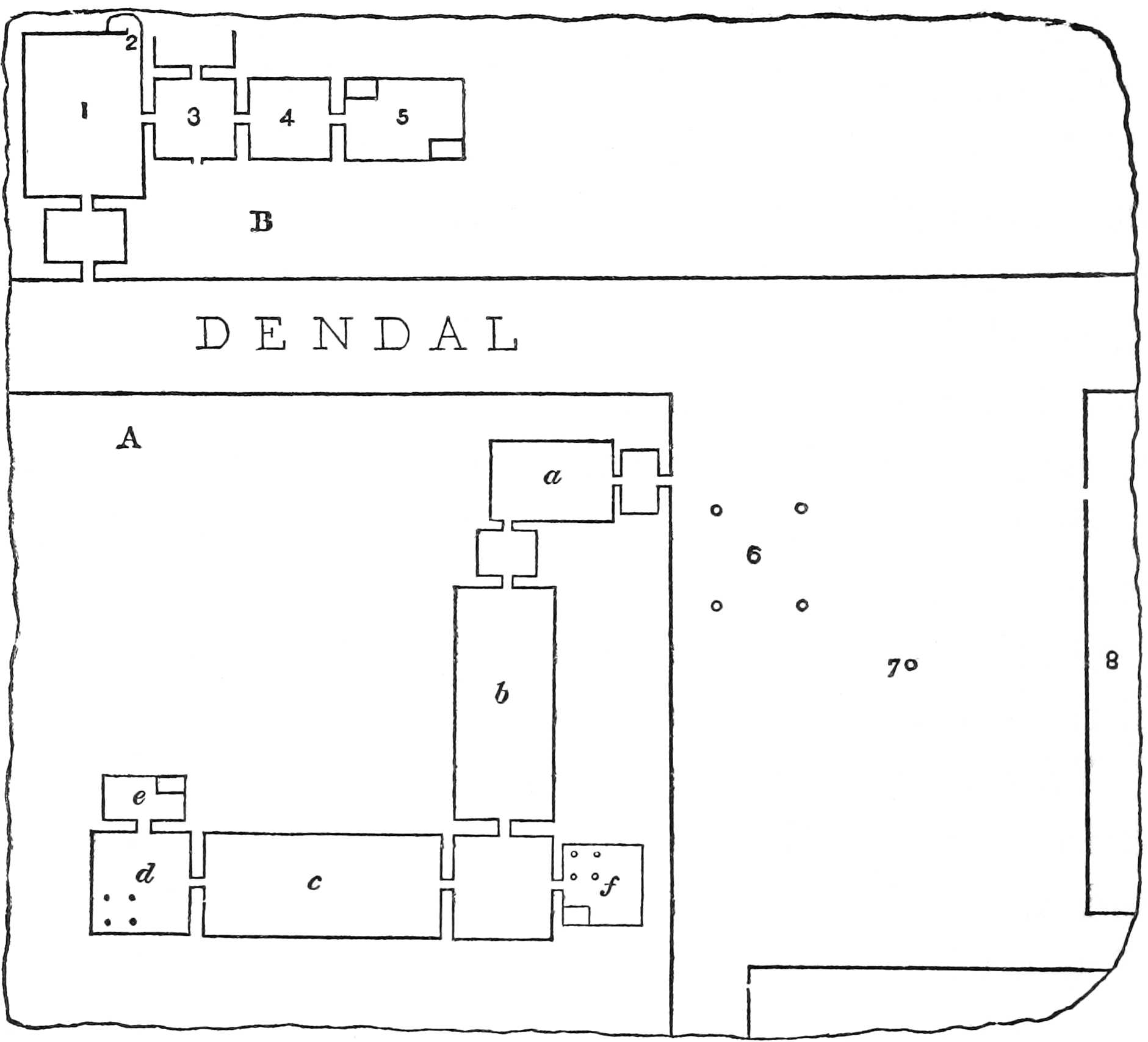

| Return to Bórnu | 229 |

| Another Alarm. — Policy of Negroland. — Cattle Indigenous or Imported. — Another District Plundered. — The Músgu Slave. — Narrow Escape. — Attack by Bees. — African Netherlands. — Miseries of Slave-hunts. — Barren Country. — Residence of Kábishmé. — Native Architecture. — Ground-plan of a Dwelling. — Amount of Booty. — Wáza. — Encampment at Wáza. — Re-arrival at Kúkawa. | |

| CHAP. XLVI. | |

| Setting out for Bagírmi. — The Country of Kótokó | 260 |

| Mestréma the Consul of Bagírmi. — Setting out for Bagírmi. — Remains of Pagan Rites. — Poa Abyssinica. — The Water. — Arborescent Euphorbiacea — Scarcity of Water. — Ngála; Buildings; Language. — Rén. — Áfadé. — Historical View of Kótokó. — Former towns of the Soy. | |

| CHAP. XLVII. | |

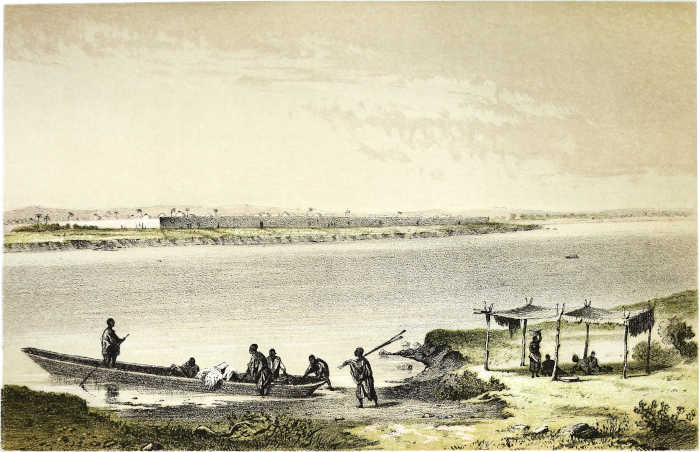

| Province of Logón. — Logón Bírni | 281 |

| Kála, New Character. — Húlluf. — The Deléb-palm again. — Reception in the Kárnak. — The Ibálaghwán. — Palace of the Sultan. — Sultan Ýsuf. — The River. — The Water-king. — Embarking on the River. — Names of Rivers. — Bathing in the River. — Historical Account of Logón. — Date of their Islám. — Government. — Food. — Manufactures. — Language. | |

| [vi]CHAP. XLVIII. | |

| The two Rivers. — Entrance into Bagírmi | 310 |

| Crossing the River. — Animated Scenery. — Political State of the Country. — The Real Shárí. — River Scenery. — Sent back by the Ferrymen. — Intrigues and Fears. — Trying another Ford. — The Shárí at Mélé. — Character of the Natives. — Entering a Country by Stealth. — Overtaken. — Residence at Mélé. — Ordered to wait at Búgomán. — Character of the River. — Mustáfají. — The Shárí again. — Sent back from Búgomán. — Búgarí. — Mókorí. — Arrival at Bákadá. — Háj Bú-Bakr Sadík. — Decay of Bagírmi. — Destructive Insects. — Character of Bákadá. — The Natives. — Intercourse. — Trees of Negroland. — Return of Messenger. | |

| CHAP. XLIX. | |

| Endeavour to leave the Country. — Arrested. — Final Entrance into Más-eñá. — Its characteristic Features | 351 |

| Stay in Mókorí. — Importance of Needles. — Want of Water. — Leaving the right Track. — A Night in the Wilderness. — Kókoroché. — Mélé again. — Laid in Irons. — Released. — Return Eastward. — Arrival at the Capital. — The Lieutenant-governor. — Háj Áhmed. — The Fáki Sámbo. — Mohammedan Learning. — The Fáki Íbrahím. — Suspected of being a Rain-maker. — Superstition of the Natives. — Becoming Retail Dealer. — The Market. — Articles of Commerce. — Difficulties of a Journey into Wádáy. — Market of Ábú-Gher. | |

| CHAP. L. | |

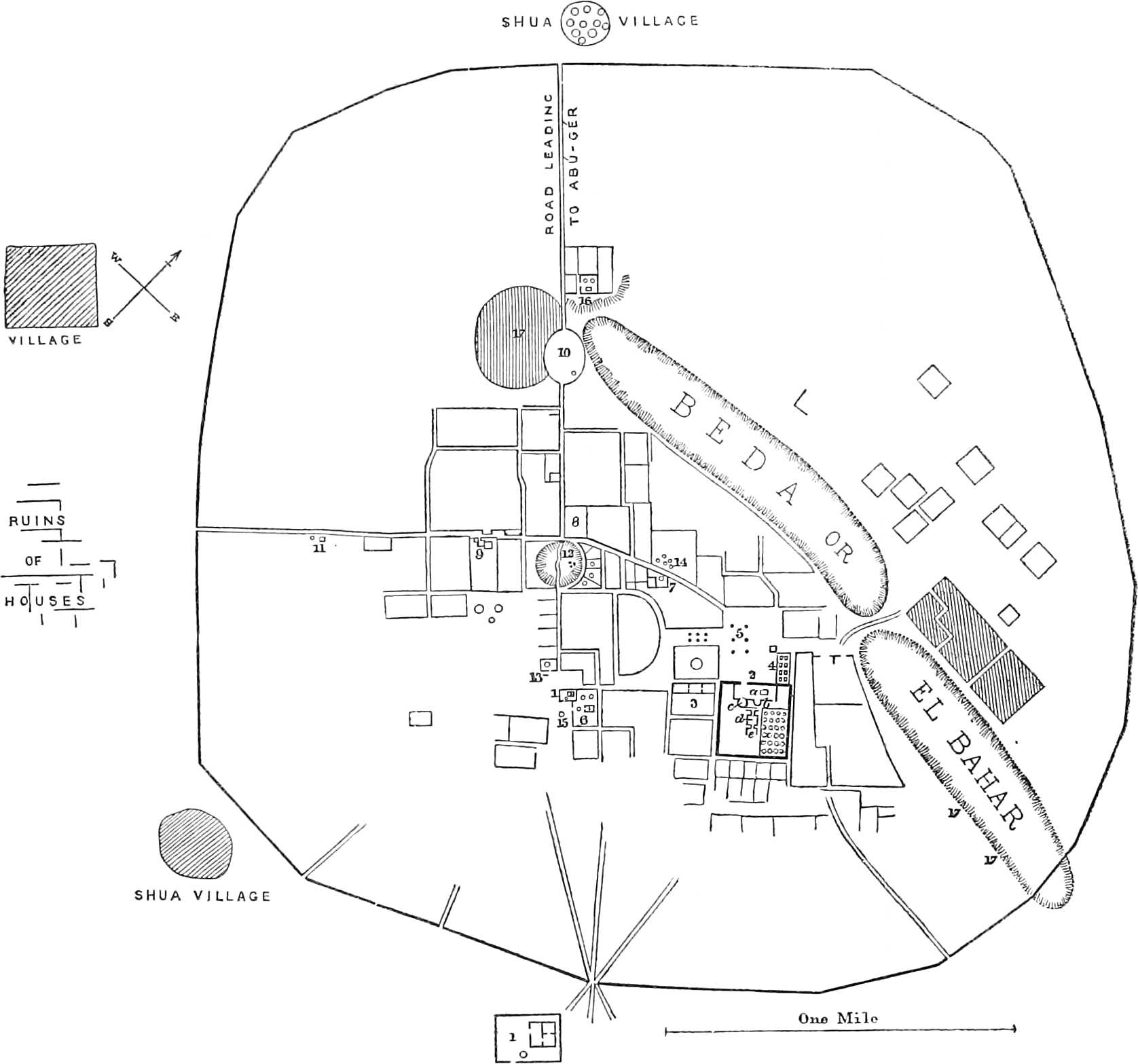

| Description of the Town. — Arrival of the Sultan. — Final Departure | 388 |

| General Character of Más-eñá. — The Palace. — The Bedá. — Patients. — The other Sex. — Occurrences of Daily Life. — Battle with Ants. — Arrival of the Sultan. — The Sultan’s Retinue. — His Entry into the Town. — Despatches and Letters. — A Serious Visit. — Escape by Frankness. — Audience with the Sultan. — Asked for a Cannon. — Pardoning Enemies. — Death of Máina Beládemí. — Present from the Sultan. — Reward of Friends. — Departure from the Capital. | |

| [vii]CHAP. LI. | |

| Historical Survey of Bagírmi. — General Condition of the Country and its Inhabitants | 425 |

| Scarcity of Information. — The Dájó. — The Kingdom of Gaoga. — Introduction of Islám. — Early History of Bagírmi. — Foundation of Más-eñá. — The Kings ʿAbd-Allah and Mohammed. — Restless Reign of ʿOthmán. — Subjection to Wádáy. — Struggle with Bórnu. — The Present King ʿAbd el Káder. — His Policy. — General Character of Bagírmi. — Mountain Gére. — No Snow on Mountains. — Edible Poa. — Vegetable Produce. — Arms. — Language. — Dress. — Government. — Tribute. — Power of the Sultan. | |

| CHAP. LII. | |

| Home-journey to Kúkawa. — Death of Mr. Overweg | 456 |

| Pleasant Starting. — Bákadá Hospitality. — Ásu and the Shárí. — The Shúwa of Mókoró. — River of Logón. — Difficulty of Proceeding without Delay. — Áfadé. — Crossing Rivers. — Bogheówa. — Meeting with Mr. Overweg. — Treaty signed. — Money-matters. — Rising of the Komádugu. — Mr. Overweg’s last Excursion. — Death of Mr. Overweg. — His Grave on the Shore of the Tsád. | |

| APPENDIX I. | ||

| Account of the Eastern Parts of Kánem, from Native Information | 481 | |

| Mʿawó and its Neighbourhood | 483 | |

| I. — | Itinerary from Mʿawó to Tághghel, directly South | 484 |

| II. — | From Berí to Tághghel, going along the Border of the Lake | 486 |

| III. — | The Bahr el Ghazal, called “Burrum” by the Kánembú, and “Féde” by the Tebu Gurʿaán | 487 |

| Mondó, Egé, Búrku, Tribes of the Tebu or Tedá | 489 | |

| [viii]APPENDIX II. | ||

| Geographical Details contained in “the Diván,” or Account given by the Imám Áhmed ben Sofíya of the Expeditions of the King Edrís Alawóma from Bórnu to Kánem | 498 | |

| First Expedition | 498 | |

| Second Expedition | 507 | |

| Third Expedition | 508 | |

| Fourth Expedition | 511 | |

| Fifth Expedition | 517 | |

| Last Expedition to the Borders of Kánem; Treaty | 519 | |

| APPENDIX III. | ||

| Account of the various Detachments of Cavalry composing the Bórnu Army in the Expedition to Músgu | 521 | |

| APPENDIX IV. | ||

| Towns and Villages of the Province of Logón or Lógone | 525 | |

| APPENDIX V. | ||

| Copy of a Despatch from Lord Palmerston | 526 | |

| APPENDIX VI. | ||

| Historical Sketch of Wádáy | 528 | |

| APPENDIX VII. | ||

| Ethnographical Account of Wádáy | 539 | |

| APPENDIX VIII. | ||

| Government of Wádáy | 554 | |

| [ix]APPENDIX IX. | ||

| Collection of Itineraries for fixing the Topography of Wádáy, and those parts of Bagírmi which I did not visit myself | 563 | |

| I. — | Roads from Más-eñá to Wára | 563 |

| II. — | Routes in the Interior of Wádáy | 570 |

| III. — | Routes in the Interior of Bagírmi | 588 |

| APPENDIX X. | ||

| Fragments of a Meteorological Register | 617 | |

[x]LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

IN

THE THIRD VOLUME.

| MAPS. | |||

| Page | |||

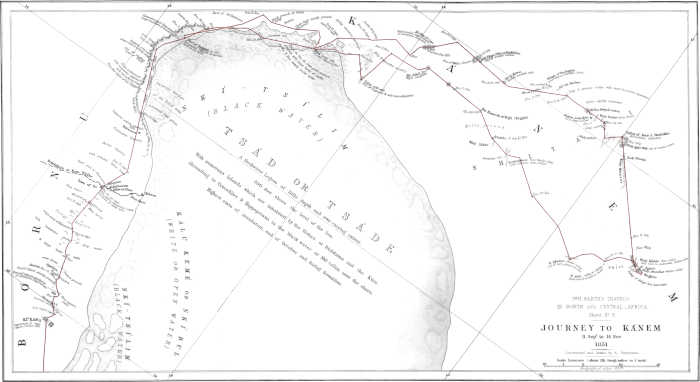

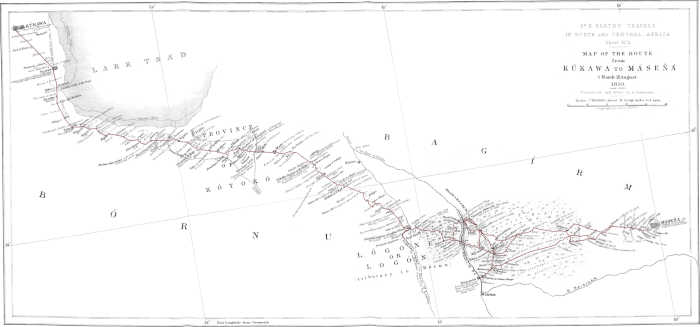

| IX. | Journey to Kánem | 23 | |

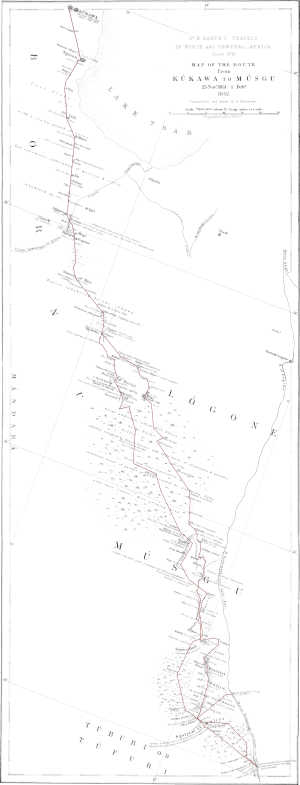

| X. | Expedition to Músgu | 118 | |

| XI. | Kúkawa to Más-eñá | 260 | |

| PLATES. | |||

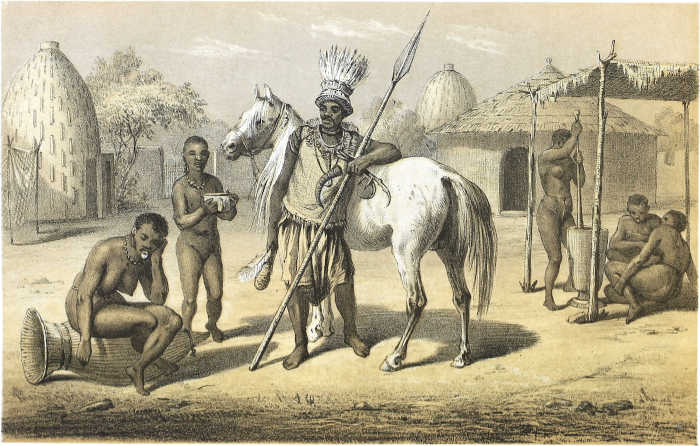

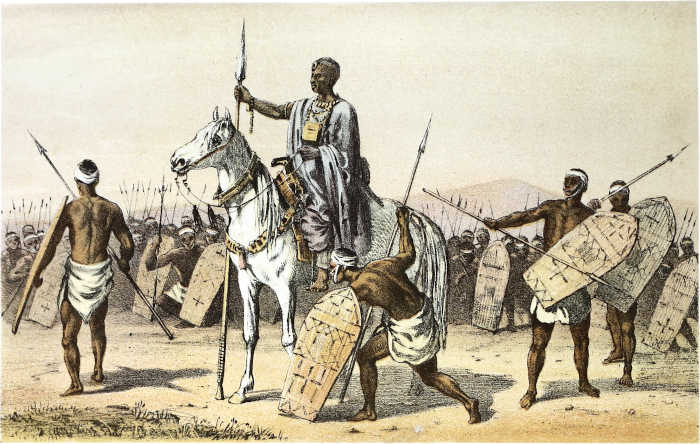

| 1. | Músgu Chief | Frontispiece | |

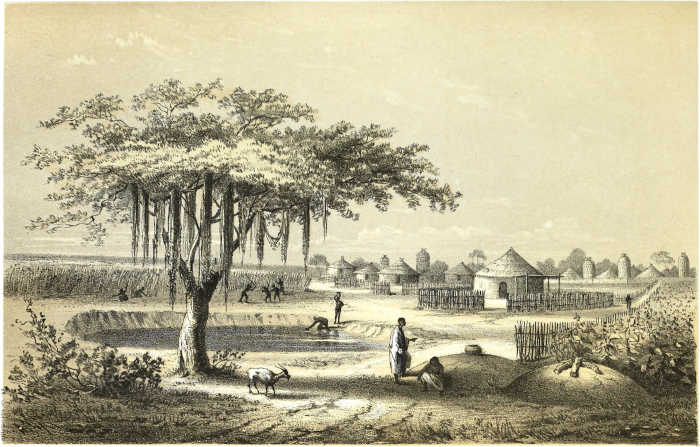

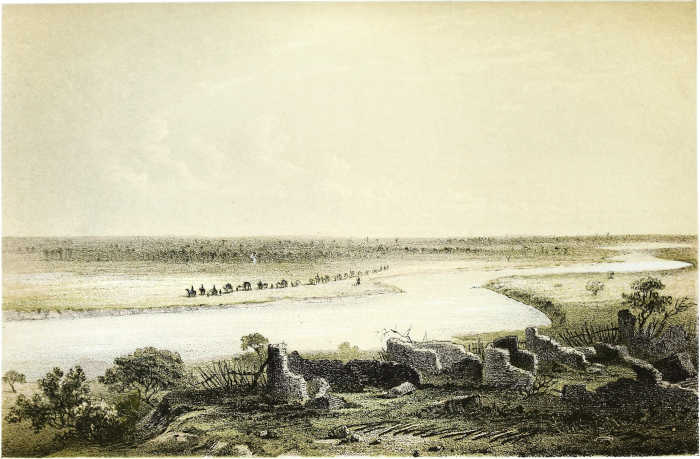

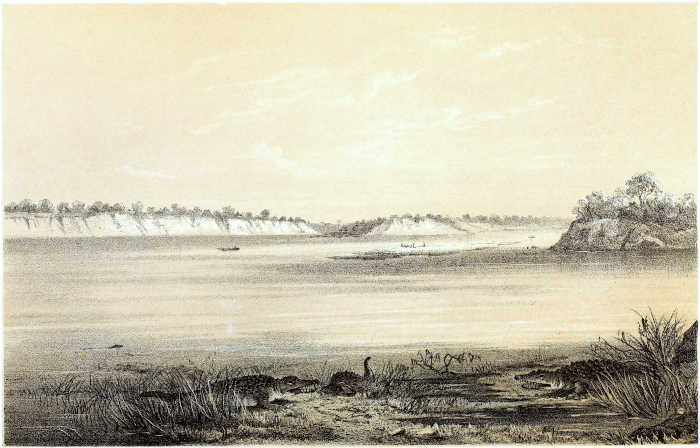

| 2. | Yó and the Komádugu | to face | 35 |

| 3. | Herd of Elephants near the Tsád | „ | 48 |

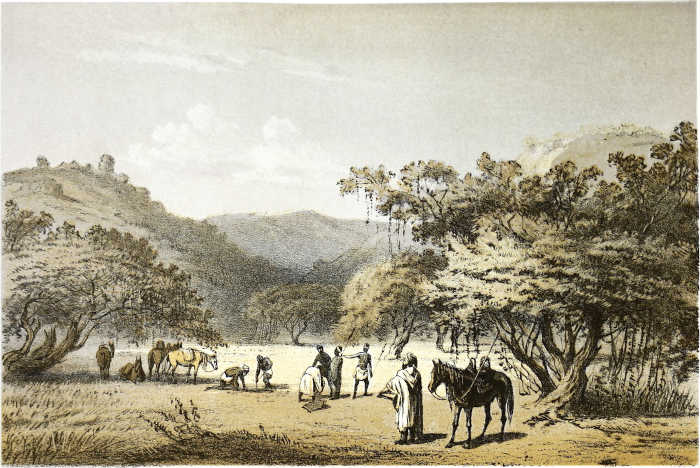

| 4. | Bír El Ftáim | „ | 82 |

| 5. | Hénderi Síggesí | „ | 96 |

| 6. | Kánembú Chief | „ | 116 |

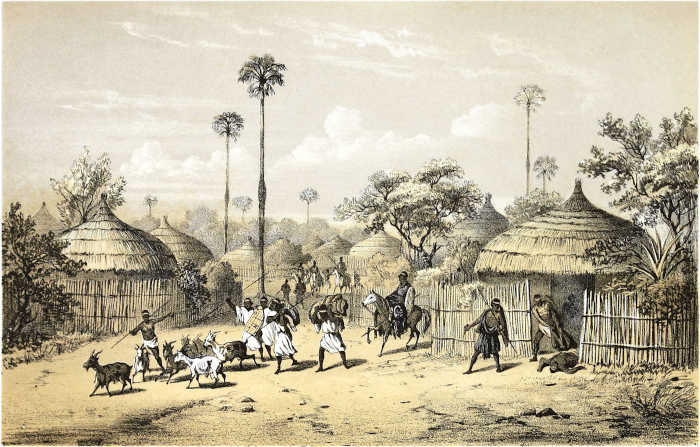

| 7. | Landscape of the Músgu Country | „ | 190 |

| 8. | Encampment in Forest | „ | 196 |

| 9. | Shallow Water (Ngáljam) at Démmo | „ | 202 |

| 10. | Landscape in Wúliya | „ | 232 |

| 11. | Bárëa and the Deléb Palm | „ | 236 |

| 12. | Interior of Dwelling | „ | 250 |

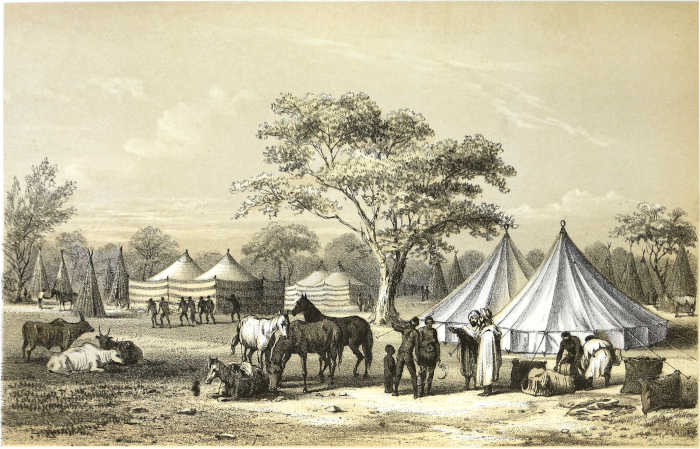

| 13. | Encampment at Wáza | „ | 256 |

| 14. | Logón Bírni | „ | 310 |

| 15. | The Shárí at Mélé | „ | 319 |

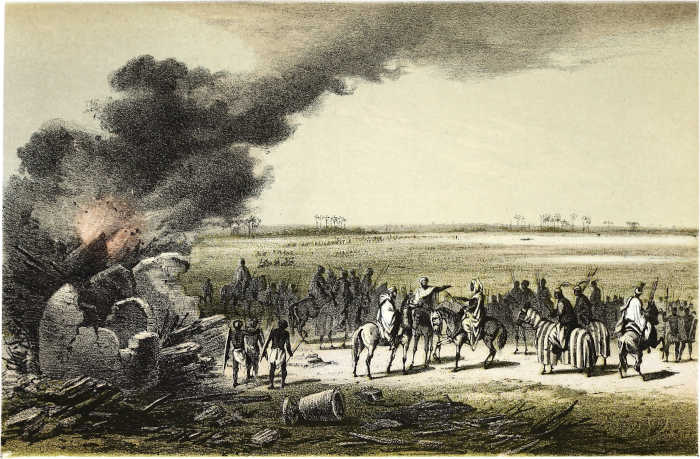

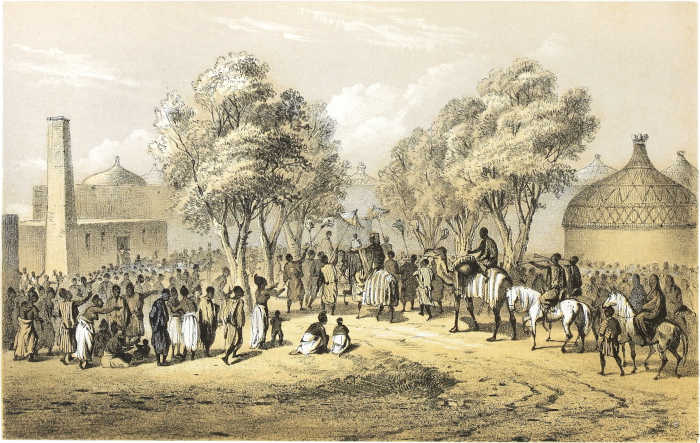

| 16. | Más-eñá, Return of the Sultan from the Expedition | „ | 405 |

| [xi]WOODCUTS. | |||

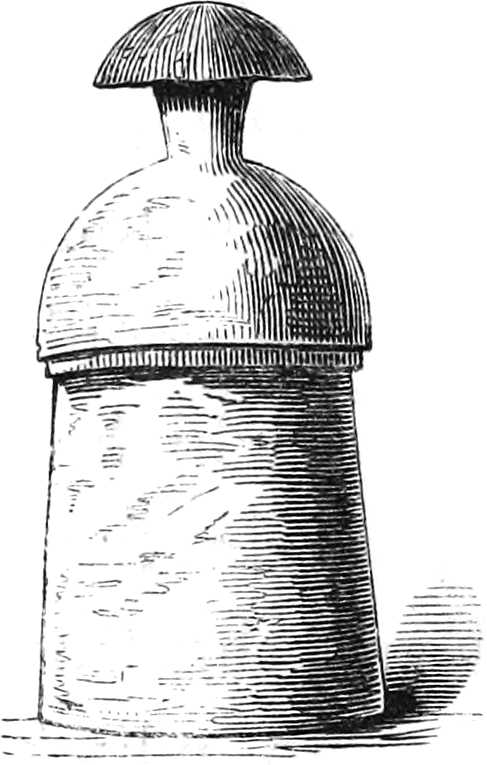

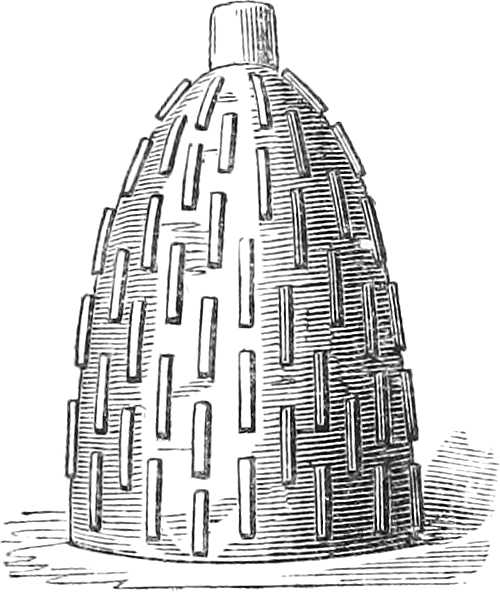

| Granary | 176 | ||

| Harpoon | 237 | ||

| Ornamented Granary | 249 | ||

| Ground-plan of Building | 250 | ||

| Ground-plan of Palace in Logón Bírni | 292 | ||

| Ground-plan of Town of Más-eñá | to face | 388 | |

ERRATA, VOL III.

| Page | 203., | line | 6. | read “south-west” instead of “south-east.” |

| „ | 240., | „ | 5. | from below, “southerly” instead of “westerly.” |

| „ | 298., | „ | 16. | “wórzi” or “berdí” instead of “wórzi berdí.” |

[1]TRAVELS AND

DISCOVERIES

IN

AFRICA.

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

RAINY SEASON IN KÚKAWA.

I had left Kúkawa on my journey to Ádamáwa in the best state of health, but had brought back from that excursion the germs of disease; and residence in the town, at least at this period of the year, was not likely to improve my condition. It would certainly have been better for me, had I been able to retire to some more healthy spot; but trivial though urgent business obliged me to remain in Kúkawa.

It was necessary to sell the merchandize which had at length arrived, in order to keep the mission in some way or other afloat, by paying the most urgent debts and providing the necessary means for further exploration. There was merchandize to the value of one hundred pounds sterling; but, as I was obliged to sell the things at a reduced[2] rate for ready money, the loss was considerable; for all business in these countries is transacted on two or three months’ credit, and, after all, payment is made, not in ready money, but chiefly in slaves. It is no doubt very necessary for a traveller to be provided with those various articles which form the presents to be made to the chiefs, and which are in many districts required for bartering; but he ought not to depend upon their sale for the supply of his wants. Altogether it is difficult to carry on trade in conjunction with extensive geographical research, although a person sitting quietly down in a place, and entering into close relations with the natives, might collect a great deal of interesting information, which would probably escape the notice of the roving traveller, whose purpose is rather to explore distant regions. Besides, I was obliged to make numerous presents to my friends, in order to keep them in good humour, and had very often not only to provide dresses for themselves and their wives, but even for their domestic retainers; so that, all things considered, the supply of one hundred pounds’ worth of merchandize could not last very long.

I have remarked that, when I re-entered Kúkawa, the cultivation of the ground had not yet begun; indeed, the whole country was so parched, that it became even a matter of perplexity to find sufficient fodder for the horses; for the whole stock of dry herbage was consumed, and of young herbage none was to be had.

[3]It is stated in my memoranda, that on the 5th of August I paid twelve rotl for a “kéla kajímbe,” or large bundle of dry grass; an enormous price in this country, and sufficient to maintain a whole family for several days; but that was the most unfavourable moment, for in a few days fresh herbage sprang up and made good all deficiencies. While speaking on this subject, I may also mention, that the herbage of Kúkawa, being full of “ngíbbi,” or Pennisetum distichum, horses brought from other countries generally fare but badly on it, as they are reluctant to fill their mouths with its small prickles.

Rain was very plentiful this year, 1851, and I am sure would, if measured, have far exceeded the quantity found by Mr. Vogel in 1854. Indeed, there were twelve very considerable falls of rain during the month of August alone, which together probably exceeded thirty inches. It must be borne in mind, moreover, that the fall of rain in Kúkawa does not constitute the rule for the region, but is quite exceptional, owing to the entire absence of trees and of heights in the neighbourhood. Hence, the statement of Mr. Vogel in one of his letters[1], that the line of tropical rains only begins south of Kúkawa, must be understood with some reserve; for if he had measured the rain in the woody country north of that capital, between Dáwerghú and Kalíluwá, he would, in my[4] opinion, have obtained a very different result. It is evident that all depends upon the meaning of the expression, tropical rain. If it imply a very copious fall of rain, Kúkawa certainly does not lie within the limit of tropical rain; but if we are to understand by it the regularly returning annual fall of rain, produced by the ascending currents of heated air, it certainly does.[2] There was a very heavy fall of rain on the night of the 3rd of August, which not only swamped our courtyard, but changed my room, which lay half a foot lower, and was protected only by a low threshold, into a little lake, aggravating my feverish state very considerably, and spoiling most of my things.

On the 5th of August rain fell for the first time unaccompanied by a storm, though the rainy season in general sets in with dreadful tornadoes. The watery element disturbed the luxurious existence of the “kanám galgálma,” the large termites, which had fed on our sugar and other supplies, and on the 6th they all of a sudden disappeared from the ground, and filled the air as short-lived winged creatures, in which state they are called by the people “tsútsu,” or “dsúdsu,” and, when fried, are used as food. Their[5] tenure of life is so precarious, and they seem to be so weak, that they become very troublesome, as they fall in every direction upon man and his food. Of each swarm of these insects only one couple seems destined to survive; all the rest die a violent death.

The town now began to present quite a different appearance; but while it was agreeable to see the dryness relieved, and succulent grass and fresh crops springing up all around, and supplanting the dull uniformity of the Asclepias gigantea, on the other hand, the extensive waterpools formed everywhere in the concavities of the ground, were by no means conducive to health, more especially as those places were depositories of all sorts of offal, and of putrefying carcasses of many kinds. The consequence was that my health, instead of improving, became worse, although I struggled hard, and as often as possible rode out on horseback. All the people were now busy in the labours of the field, although cultivation in the neighbourhood of the town is not of a uniform, but of a varied character; and a large portion of the ground, consisting of “ánge” and “fírki,” is reserved for the culture of the masákuwá (Holcus cernuus), or winter-corn, with its variety the kérirám.

On the 8th of August the neighbourhood presented a very animated spectacle, the crownlands in Gawánge being then cultivated by a great number of people, working to the sound of a drum. Their labours continued till the 15th; on which day Mr.[6] Overweg had the honour of presenting his Búdduma friends to the sheikh of Bórnu. All nature was now cheerful; the trees were putting forth fresh leaves, and the young birds began to fledge. I took great delight in observing the little household of a family of the feathered tribe; there were five young ones, the oldest and most daring of which began to try his strength on the 12th of August, while the other four set out together on the 14th.

Marriages are not frequent about this time, on account of the dearness of corn; but matches are generally made after the harvest has been got in, and while corn is cheap. I shall speak in another place of the marriage ceremonies of this country.

On the 5th of September we obtained the first specimen of new “argúm móro,” white Negro millet, which is very pleasant to the taste when roasted on the fire; but this is regarded as a rarity, and new corn is not brought into the market in any great quantities before the end of November, or rather the beginning of December, when all the corn, which has been for a long time lying in the fields in conical heaps, called “búgga,” is threshed out.

My friend, the vizier, whose solicitude for my health I cannot acknowledge too warmly, was very anxious that I should not stay in the town during the rainy season; and knowing that one of our principal objects was to investigate the eastern shore of lake Tsád, sent me word, on the 11th of August, that I might now view the bahár el ghazál, an undertaking which,[7] as I have already mentioned, he had at first represented as impossible. The news from Kánem, however, was now favourable; but as I shall speak in another place of the political state of this distracted country, and of the continual struggle between Bórnu and Wadáÿ, I need only mention here that the Welád Slimán, who had become a mercenary band attached to the vizier, had been successful during their last expedition, and were reported on the very day of my return from Ádamáwa to have made a prize of 150 horses and a great many camels, which, however, was a great exaggeration.

We were well acquainted with the character of these people, who are certainly the most lawless robbers in the world; but as it was the express wish of the British government that we should endeavour to explore the regions bordering on the lake, there was no course open to us, but to unite our pursuits with theirs; besides, they were prepared in some measure for such a union, for, while they inhabited the grassy lands round the great Syrtis, they had come into frequent contact with the English. We had no choice, for all the districts to the north-east and east of the Tsád were at present in a certain degree dependent on Wadáÿ, then at war with Bórnu, and we were told at the commencement that we might go anywhere except to Wadáÿ. Instead of fighting it out with his own people, which certainly would have been the most honourable course, the vizier had ventured to make use of the remnant of[8] the warlike, and at present homeless, tribe of the Welád Slimán, in the attempt to recover the eastern districts of Kánem from his eastern rival; or at least to prevent the latter from obtaining a sure footing in them; for this object he had made a sort of treaty with these Arabs, undertaking to supply them with horses, muskets, powder and shot. Thus, in order to visit those inhospitable regions, which had attracted a great deal of attention in Europe, we were obliged to embrace this opportunity. Under these circumstances, on the 16th of August, I sent the vizier word that I was ready to join the Welád Slimán in Búrgu; whereupon he expressed a wish that Mr. Overweg might likewise accompany us; the stay in Kúkawa during the rainy season being very unhealthy.

Mr. Overweg had returned on the 9th to Maduwári from his interesting voyage on the Tsád, of which everyone will deeply regret that he himself was not able to give a full account.[3] Traversing that shallow basin in the English boat, which we had carried all the way through the unbounded sandy wastes and the rocky wildernesses of the desert, he had visited a great part of the islands, which are dispersed over its surface, and which, sometimes reduced to narrow sandy downs, at others expanding to wide grassy lowlands, sustain a population in their peculiar national independence, the remnant of a great nation which was exterminated by the Kanúri. It was a[9] little world of its own with which he had thus come into contact, and into which we might hope to obtain by degrees a better insight. He enjoyed excellent health, far better than when I saw him before, on his first rejoining me in Kúkawa; and as he was well aware of the strong reasons which our friend the vizier had for wishing us not to stay in the swampy lowlands round the capital during the latter part of the rainy season, he agreed to join me on this adventurous expedition to the north-east.

Those regions had, from the very beginning of our setting out from Múrzuk, attracted Mr. Overweg’s attention, and while as yet unacquainted with the immense difficulties that attend travelling in these inhospitable tracts, he had indulged in the hope of being able, at some future time, to ramble about with our young Tébu lad, Mohammed el Gatróni, among the fertile and picturesque valleys of Búrgu and Wajánga. For this reason, as well as on account of my debility, which left me, during the following expedition, the exercise of only a small degree of my natural energy, it is greatly to be regretted that my unfortunate companion, who seemed never fully aware that his life was at stake, did not take into consideration the circumstance that he himself might not be destined to return home, in order to elaborate his researches. If all the information which he occasionally collected were joined to mine, those countries would be far better known than they now are; but instead of employing his[10] leisure hours in transcribing his memoranda in a form intelligible to others, he left them all on small scraps of paper, negligently written with lead pencil, which after the lapse of some time would become unintelligible even to himself. It is a pity that so much talent as my companion possessed was not allied with practical habits, and concentrated upon those subjects which he professed to study.

The political horizon of Negroland during this time was filled with memorable events, partly of real, partly of fictitious importance. Whatever advantages Bórnu may derive from its central position, it owes to it also the risk of being involved in perpetual struggles with one or other of the surrounding countries. And hence it is that, under a weak government, this empire cannot stand for any length of time; it must go on conquering and extending its dominion over adjacent territories, or it will soon be overpowered. Towards the north is the empire of the Turks, weak and crumbling in its centre, but always grasping with its outlying members, and threatening to lay hold of what is around: towards the north-west, the Tawárek, not forming a very formidable united power, but always ready to pounce upon their prey whenever opportunity offers: towards the west, the empire of Sókoto, great in extent, but weak beyond description in the unsettled state of its loosely connected provinces, and from the unenergetic government of a peacefully disposed prince; for while one provincial governor was just then spreading around[11] him the flames of sedition and revolt, towards the south another vassal of this same empire was disputing the possession of those regions whence the supply of slaves is annually obtained: and towards the east, there is an empire strong in its barbarism, and containing the germs of power, should it succeed in perfectly uniting those heterogeneous elements of which it is composed,—I mean Wadáÿ.

With regard to the Turks, the state of affairs at this time was peculiar. Bórnu, as we have seen in the historical account of that empire, once embraced the whole region as far as Fezzán,—nay, even the southern portion of Fezzán itself, and even Wadán; but since the decline of the empire in the latter half of the last century these limits had been abandoned, and the communication with the north had, in general, become extremely unsafe. This state of things is necessarily disadvantageous to a country which depends for many things on the supplies conveyed from the north; and the authorities naturally wish that, since they themselves in their present impotent condition are unable to afford security to this important communication, somebody else may do it. Hence it was that, after my arrival in April, when the vizier was conversing with me about the prospects of a regular commercial intercourse with the English, he declared that he should be much pleased if the Turks would occupy Kawár, and more particularly Bílma; and by building a fort and keeping a garrison near the salt-mines of that place,[12] exercise some control over the Tawárek of Aïr, and make them responsible for robberies committed on the Fezzán road. It was in consequence of this communication that I begged Her Majesty’s government to enter into communication upon this point with the Porte.

But the matter was of a very delicate nature with regard to Bórnu. Indeed, it seemed questionable whether the Turks, if once firmly established in Bílma, would not think fit to exercise some control over the latter country. Nay, it was rather to be feared that they might try to obtain there a firm footing, in order to extend their empire; and when the news arrived in Bórnu that the ambitious Hassan Bashá had returned to his post as governor of Fezzán, with very ample instructions, the whole court of Bórnu became alarmed. The effect of this news upon the disposition of the sheikh and the vizier to enter into friendly relations with the British government was remarkable. On the 5th of August they were not able to conceal their fear lest a numberless host of Englishmen might come into their country, if, by signing the treaty, access was once allowed them, as proposed by Her Majesty’s government. For although they were conscious of the poverty of their country in comparison with Europe, at times they were apt to forget it. In the afternoon of the 6th the courier arrived, and the same evening Háj Beshír sent me word that they were ready to sign the treaty; and afterwards they were very anxious that the English[13] government should endeavour to prevent the governor of Fezzán from carrying out the ulterior objects of his ambition. At that time I had assured myself that a northern road through the desert was not suitable for European commerce, and that a practicable highroad, leading several hundred miles into the interior of the continent and passing to the south of Kanó, the great commercial entrepôt of Central Africa, and only about two hundred miles in a straight line to the south of Kúkawa, had been found in the river Bénuwé.

With regard to the empire of Sókoto, there happened at this time a catastrophe which, while it was an unmistakeable proof of the debility of that vast agglomeration of provinces, proved at the same time extremely favourable to Bórnu. For on the 1st of August the news arrived that Bowári or Bokhári, the exiled governor of Khadéja, who had conquered the town and killed his brother, had thrown back, with great loss, an immense army sent against him by ʿAlíyu, the emperor of Sókoto, under the command of his prime minister, ʿAbdu Gedádo, and composed of the forces of the provinces of Kanó, Báuchi, Katágum, Mármar, and Bobéru, when several hundreds were said to have perished in the komádugu, or the great fiumara of Bórnu. In the spring, while Mr. Overweg was staying in Góber, the Mariadáwa and Goberáwa had made a very successful expedition into Zánfara; and the emperor of Sókoto could take no other revenge upon them, than by sending orders to Kanó that my friends the Asbenáwa, many of whose brethren had taken part[14] in the expedition, should be driven out of the town, which order was obeyed; while only the well-known Kandáke, the same man whom Mr. Richardson, on his former journey into the desert, has so frequently mentioned, was admitted into the town through the intercession of the people of Ghadámes.

The immediate consequence of these circumstances was, that the court of Bórnu tried to enter into more friendly relations with the Asbenáwa, or the Tawárek of Asben, with whom at other times they were on unfriendly terms, and the prisoners whom they had made on the last expedition were released. The coalition extended as far as Góber; and the most ardent desire of the vizier was to march straight upon Kanó. To conquer this great central place of commerce was the great object of this man’s ambition; but for which he did not possess sufficient energy and self-command. However, the governor of that place, terrified by the victory of Bokhári, who was now enabled to carry on his predatory expeditions into that rich territory without hindrance, distributed sixty bernúses and three thousand dollars among the Mʿallemín, to induce them to offer up their prayers to Allah for the public welfare.

We have seen above, that the Bórnu people had given to their relations with Ádamáwa a hostile character; but from that quarter they had nothing to fear, the governor of that province being too much occupied by the affairs of his own country.

I will now say a word about Wadáÿ. That was the[15] quarter to which the most anxious looks of the Bórnu people were directed. For, seven years previously, they had been very nearly conquered by them, and had employed every means to get information of what was going on there. But from thence also the news was favourable. For although the report of the death of the Sultan Mohammed Sheríf, in course of time, turned out to be false, still it was true that the country was plunged into a bloody civil war with the Abú-Senún, or Kodoyí, and that numbers of enterprising men had succumbed in the struggle.

The business of the town went on as usual, with the exception of the ʿaid el fotr, the ngúmerí ashám, the festival following the great annual fast, which was celebrated in a grand style, not by the nation, which seemed to take very little interest in it, but by the court. In other places, like Kanó, the rejoicings seem to be more popular on this occasion; the children of the butchers or “masufauchi” in that great emporium of commerce mounting some oxen, fattened for the occasion, between the horns, and managing them by a rope fastened to the neck, and another to the hind leg. As for the common people of Bórnu, they scarcely took any other part in this festivity than by putting on their best dresses; and it is a general custom in larger establishments that servants and attendants on this day receive a new shirt.

I also put on my best dress, and mounting my horse, which had recovered a little from the fatigue of[16] the last journey, though it was not yet fit for another, proceeded in the morning to the eastern town or “billa gedíbe,” the great thoroughfare being crowded with men on foot and horseback, passing to and fro, all dressed in their best. It had been reported that the sheikh was to say his prayers in the mosque, but we soon discovered that he was to pray outside the town, as large troops of horsemen were leaving it through the north gate or “chinna yalábe.” In order to become aware of the place where the ceremony was going on, I rode to the vizier’s house and met him just as he came out, mounted on horseback, and accompanied by a troop of horsemen.

At the same time several cavalcades were seen coming from various quarters, consisting of the kashéllas, or officers, each with his squadron, of from a hundred to two hundred horsemen, all in the most gorgeous attire, particularly the heavy cavalry; the greater part being dressed in a thick stuffed coat called “degíbbir,” and wearing over it several tobes of all sorts of colours and designs, and having their heads covered with the “búge” or casque, made very nearly like those of our knights in the middle age, but of lighter metal, and ornamented with most gaudy feathers. Their horses were covered all over with the thick clothing called “líbbedí,” with various coloured stripes, consisting of three pieces, and leaving nothing but the feet exposed, the front of the head being protected and adorned by a metal plate. Others were dressed in a coat of mail, “síllege,” and the other kind[17] called “komá-komí-súbe.” The lighter cavalry was only dressed in two or three showy tobes and small white or coloured caps; but the officers and more favoured attendants wore bernúses of finer or coarser quality, and generally of red or yellow colour, slung in a picturesque manner round the upper part of their body, so that the inner wadding of richly coloured silk was most exposed to view.[4]

All these dazzling cavalcades, amongst whom some very excellent horses were seen prancing along, were moving towards the northern gate of the “billa gedíbe,” while the troop of the sheikh himself, who had been staying in the western town, was coming from SW. The sight of this troop, at least from a little distance, as is the case in theatrical scenery, was really magnificent. The troop was led by a number of horsemen; then followed the livery slaves with their matchlocks; and behind them rode the sheikh, dressed as usual in a white bernús, as a token of his religious character, but wearing round his head a red shawl. He was followed by four magnificent chargers clothed in líbbedí of silk of various colours; that of the first horse being striped white and yellow, that of the second white and brown, that of the third white and light green, and that of the fourth white and cherry red. This was certainly the most interesting and conspicuous part of the procession. Behind the horses followed the[18] four large ʿalam or ensigns of the sheikh, and the four smaller ones of the musketeers, and then a numerous body of horsemen.

This cavalcade of the sheikh’s now joined the other troops, and the whole body proceeded in the direction of Dawerghú to a distance of about a mile from the town. Here the sheikh’s tent was pitched, consisting of a very large cupola of considerable dimensions, with blue and white stripes, and curtains, the one half white and the other red; the curtains were only half closed. In this tent the sheikh himself, the vizier, and the first courtiers were praying, while the numerous body of horsemen and men on foot were grouped around in the most picturesque and imposing variety.

Meanwhile I made the round of this interesting scene, and endeavoured to count the various groups. In their numbers I was certainly disappointed, as I had been led to expect myriads. At the very least, however, there were 3000 horsemen, and from 6000 to 7000 armed men on foot, the latter partly with bow and arrow. There were besides a great multitude of spectators. The ceremony did not last long; and as early as nine o’clock the ganga summoned all the chiefs to mount, and the dense mass of human beings began to disperse and range themselves in various groups. They took their direction round the north-western corner of the east town, and entered the latter by the western gate; but the crowd was so great that I chose to forego taking leave of the sheikh, and went slowly back over the[19] intermediate ground between the two towns in the company of some very chevaleresque and well-mounted young Arabs from Ben-Gházi, and posted myself at some distance from the east-gate of the western town, in order to see the kashéllas, who have their residence in this quarter, pass by.

There were twelve or thirteen, few of whom had more than one hundred horsemen, the most conspicuous being Fúgo ʿAli, ʿAli Marghí, ʿAli Déndal, ʿAli Ladán, Belál, Sálah Kandíl, and Jerma. It was thought remarkable that no Shúwa had come to this festivity, but I think they rarely do, although they may sometimes come for the ʿAid-el-kebír, or the “ngúmerí layábe.” It is rather remarkable that even this smaller festivity is celebrated here with such éclat, while in general in Mohammedan Negroland only the “láya” is celebrated in this way; perhaps this is due to Egyptian influence, and the custom is as old at least as the time of the King Edrís Alawóma.

I had the inexpressible delight of receiving by the courier, who arrived on the 6th of August, a considerable parcel of letters from Europe, which assured me as well of the great interest which was generally felt in our undertaking, although as yet only very little of our first proceedings had become known, as that we should be enabled to carry out our enterprise without too many privations. I therefore collected all the little energy which my sickly state had left me, and concluded the report of my journey to Ádamáwa, which caused me a great deal of pain,[20] but which, forwarded on the 8th of August, together with the news of Mr. Overweg’s successful navigation, produced a great deal of satisfaction in Europe. Together with the letters and sundry Maltese portfolios, I had also the pleasure of receiving several numbers of the “Athenæum,” probably the first which were introduced into Central Africa, and which gave me great delight.

Altogether our situation in the country was not so bad. We were on the best and most friendly terms with the rulers: we were not only tolerated, but even respected by the natives, and we saw an immense field of interesting and useful labour open to us. There was only one disagreeable circumstance besides the peculiar nature of the climate; this was the fact that our means were too small to render us quite independent of the sheikh and his vizier; for the scanty supplies which had reached us were not sufficient to provide for our wants, and were soon gone. We were scarcely able to keep ourselves afloat on our credit, and to supply our most necessary wants. Mr. Overweg, besides receiving a very handsome horse from them, had also been obliged to accept at their hands a number of tobes, which he had made presents of to the chiefs of the Búdduma, and they looked upon him as almost in their employment. He lost a great deal of his time in repairing, or rather trying to repair, their watches and other things. Such services I had declined from the beginning, and was therefore regarded as less useful;[21] and I had occasionally to hear it said, “ʿAbd el Kerím faidanse bágo,”—“ʿAbd el Kerím is of no use whatever;” nevertheless I myself was not quite independent of their kindness, although I sacrificed all I could in order to give from time to time a new impulse to their favour by an occasional present.

The horse which they had first given me had proved incapable of such fatigue as it had to undergo, and the animal which I had bought before going to Ádamáwa had been too much knocked up to stand another journey so soon; and after having bought two other camels, and prepared myself for another expedition, I was unable, with my present means, to buy a good horse. Remembering, therefore, what the vizier had told me with regard to my first horse, I sent him word that he would greatly oblige me by making me a present of one, and he was kind enough to send me four animals from which to choose; but as none of these satisfied me, I rejected them all, intimating very simply that it was impossible, among four nags, “kádara,” to choose one horse, “fir.” This hint, after a little farther explanation, my friend did not fail to understand, and in the evening of the 7th of September he sent me a horse from his own stable, which became my faithful and noble companion for the next four campaigns, and from which I did not part till, after my return from Timbúktu, in December, 1854, he succumbed to sickness in Kanó.

He was the envy of all the great men, from the[22] Sultan of Bagírmi to the chiefs of the Tademékket and Awelímmiden near Timbúktu. His colour was a shade of gray, with beautiful light leopardlike spots, and the Kanúri were not unanimous with regard to the name which they gave it, some calling it “shéggará,” while others thought the name “kerí sassarándi” more suitable to it. In the company of mares, he was incapable of walking quietly, but kept playing in order to show himself off to advantage. The Bórnu horses in general are very spirited and fond of prancing. He was an excellent “kerísa” or marcher, and “doy” or swift in the extreme, but very often lost his start by his playfulness. Of his strength, the extent of the journeys which he made with me bears ample testimony, particularly if the warlike, scientific, and victualling stores which I used to carry with me are taken into account. He was a “ngírma,” but not of the largest size. Mr. Overweg’s horse was almost half a hand higher; but while mine was a lion in agility, my companion’s horse was not unlike a hippopotamus in plumpness.

With such a horse, I prepared cheerfully for my next expedition, which I regarded in the light both of an undertaking in the interests of science, and as a medicinal course for restoring my health, which threatened to succumb in the unhealthy region of Kúkawa. Besides two Fezzáni lads, I had taken into my service two Arabs belonging to the tribe of the Welád Slimán, and whose names were Bú-Zéd and Hasén ben Hár.

[1]Published in Journal of the R. Geogr. Soc. vol. xxv., 1855, p. 241.

[2]It will perhaps be as well to call to mind the prudent warning of Col. Sykes, in reference to the observations of Prof. Dove. “These observations,” he says, “suggest to us the necessity of caution in generalizing from local facts with regard to temperatures and falls of rain.”—Report of the National Association, 1852, p. 253.

[3]I shall return to the subject of Mr. Overweg’s voyage.

[4]I shall say more on the military department in my narrative of the expedition to Músgu.

DR. BARTH’S TRAVELS

IN NORTH AND CENTRAL AFRICA

Sheet No. 9.

JOURNEY TO

KÁNEM

11. Sept. To 14. Nov.

1851.

Constructed and drawn by A. Petermann.

Engraved by E. Weller, Duke Strt. Bloomsbury.

London, Longman & Co.

[23]CHAP. XXXIX.

EXPEDITION TO KÁNEM.

September 11th, 1851.Having decided upon leaving the town in advance of the Arabs, in order to obtain leisure for travelling slowly the first few days, and to accustom my feeble frame once more to the fatigues of a continual march, after a rest of forty days in the town, I ordered my people to get my luggage ready in the morning.

I had plenty of provisions, such as zummíta, dwéda, or vermicelli, mohámsa, and nákia, a sort of sweetmeat made of rice with butter and honey; two skins of each quality. All was stowed away with the little luggage I intended taking with me on this adventurous journey, in two pairs of large leathern bags or kéwa, which my two camels were to carry.

When all was ready, I went to the vizier, in order to take leave of him and arrange with my former servant, Mohammed ben Sʿad, to whom I owed thirty-five dollars. Háj Beshír, as usual, was very kind and amiable; but as for my former servant, having not a single dollar in cash, I was obliged to give him a bill upon Fezzán for seventy-five dollars.[24] There was also a long talk on the subject of the enormous debt due to the Fezzáni merchant, Mohammed e’ Sfáksi; and as it was not possible to settle it at once, I was obliged to leave its definite arrangement to Mr. Overweg.

All this disagreeable business, which is so killing to the best hours and destroys half the energy of the traveller, had retarded my departure so long that the sun was just setting when I left the gate of the town. My little caravan was very incomplete; for my only companion on emerging from the gate into the high waving fields of Guinea corn, which entirely concealed the little suburb, was an unfortunate young man, whom I had not hired at all; my three hired servants having stayed behind, on some pretext or other. This lad was Mohammed ben Ahmed, a native from Fezzán, whom I wanted to hire, or rather hired, in Gúmmel, in March last, for two Spanish dollars a month; but who, having been induced by his companions in the caravan, with which he had just arrived from the north, to forego the service of a Christian, had broken his word, and gone on with the caravan of the people from Sókna, leaving me with only one useful servant. But he had found sufficient leisure to repent of his dishonourable conduct; for having been at the verge of the grave in Kanó, and being reduced to the utmost misery, he came to Kúkawa, begging my pardon, and entreating my compassion: and, after some expostulation, I allowed him to stay without hiring him; and it was only on seeing his[25] attachment to me in the course of time that I afterwards granted him a dollar a month, and he did not obtain two dollars till my leaving Zínder, in January, 1853, on my way to Timbúktu, when I was obliged to augment the salary of all my people. This lad followed me with my two camels.

All was fertility and vegetation, though these fields near the capital are certainly not the best situated in Bórnu. I felt strengthened by the fresh air, and followed the eastern path, which did not offer any place for an encampment. Looking round I saw at length two of my men coming towards us, and found to the left of the track, on a little sandy eminence, a convenient spot for pitching my tent. I felt happy in having left the monotony and closeness of the town behind me. Nothing in the world makes me feel happier than a wide, open country, a commodious tent, and a fine horse. But I was not quite comfortable; for, having forgotten to close my tent, I was greatly annoyed by the mosquitoes, which prevented my getting any sleep. The lake being very near, the dew was so heavy that next morning my tent was as wet as if it had been soaked with water.

Sept. 12th.Notwithstanding these inconveniences, I awoke in the morning with a grateful heart, and cared little about the flies, which soon began to attack me. I sat down outside the tent to enjoy my liberty: it was a fine morning, and I sat for hours tranquilly enjoying the most simple landscape (the lake not being visible, and scarcely a single tree in[26] sight) which a man can fancy. But all was so quiet, and bespoke such serenity and content, that I felt quite happy and invigorated. I did not think about writing, but idled away the whole day. In the evening my other man came, and brought me a note from Mr. Overweg, addressed to me “in campo caragæ Æthiopiensis” (karága means wilderness).

Saturday, Sept. 13th.I decided late in the morning, when the dew had dried up a little, upon moving my encampment a short distance, but had to change my path for a more westerly one, on account of the large swampy ponds, formed at the end of the rainy season in the concavity at the foot of the sand-hills of Dawerghú. The vegetation is rich during this season, even in this monotonous district.

Having at length entered the corn-, or rather millet-fields of Dawerghú, we soon ascended the sandhills, where the whole character of the landscape is altered; for while the dúm-bush almost ceases, the rétem, Spartium monospermum, is the most common botanical ornament of the ground where the cultivation of the fields has left a free spot, whilst fine specimens of the mimosa break the monotony of the fields. Having passed several clusters of cottages forming an extensive district, I saw to the right an open space descending towards a green sheet of water, filling a sort of valley or hollow, where a short time afterwards, when the summer harvest is over, the peculiar sort of sorghum called másakwá is sown. Being shaded by some fine acacias, the spot was very inviting,[27] and, feeling already tired, sick and weak as I was, though after a journey of only two hours, I determined to remain there during the heat of the day. I had scarcely stretched myself on the ground, when a man brought me word that a messenger, sent by Ghét, the chief of the Welád Slimán, had passed by with the news that this wandering and marauding tribe had left Búrgu and returned to Kánem. This was very unpleasant news, as, from all that I had heard, it appeared to me that Búrgu must be an interesting country, at least as much so as Ásben or Aïr, being favoured by deep valleys and ravines, and living sources of fine water, and producing, besides great quantities of excellent dates, even grapes and figs, at least in some favoured spots.

The morning had been rather dull, but before noon the sun shone forth, and our situation on the sloping ground of the high country, overlooking a great extent of land in the rich dress of vegetable life, was very pleasant. There was scarcely a bare spot: all was green, except that the ears of the millet and sorghum were almost ripe, and began to assume a yellowish-brown tint; but how different is the height of the stalks, the very largest of which scarcely exceeds fifteen feet, from those I saw afterwards on my return from Timbúktu, in the rich valleys of Kébbi. Several Kánembú were passing by and enlivened the scenery.

When the heat of the sun began to abate I set my little caravan once more in motion, and passed on[28] through the level country, which in the simplicity of my mind I thought beautiful, and which I greatly enjoyed. After about an hour’s march, we passed a large pond or pool, situated to the left of the road, and formed by the rains, bordered by a set of trees of the acacia tribe, and enlivened by a large herd of fine cattle. Towards evening, after some trouble, we found a path leading through the fields into the interior of a little village, called Alairúk, almost hidden behind the high stalks of millet. Our reception was rather cold, such as a stranger may expect to find in all the villages situated near a capital, the inhabitants of which are continually pestered by calls upon their hospitality. But, carrying my little residence and all the comforts I wanted with me, I cared little about their treatment; and my tent was soon pitched in a separate courtyard. But all my enjoyment was destroyed by a quarrel which arose between my horseman and the master of the dwelling, who would not allow him to put his horse where he wished: my horseman had even the insolence to beat the man who had received us into his house. This is the way in which affairs are managed in these countries.

Sunday, September 14th.After a refreshing night I started a little later than on the day previous, winding along a narrow path through the fields, where, besides sorghum, karás (Hibiscus esculentus) is cultivated, which is an essential thing for preparing the soups of the natives, in districts where the leaves of the kúka, or monkey-bread-tree, and of the[29] hajilíj, or Balanites, are wanting; for though the town of Kúkawa has received its name from the circumstance that a young tree of this species was found on the spot where the sheikh Mohammed el Kánemi, the father of the ruling sultan, laid the first foundation of the present town, nevertheless scarcely any kúka is seen for several miles round Kúkawa.

The sky was cloudy, and the country became less interesting than the day before. We met a small troop of native traders, with dried fish, which forms a great article of commerce throughout Bórnu; for though the Kanúri people at present are almost deprived of the dominion, and even the use, of the fine sheet of water which spreads out in the midst of their territories, the fish, to which their forefathers have given the name of food (bú-ni, from bú, to eat), has remained a necessary article for making their soups. The fields in this part of the country were not so well looked after, and were in a more neglected state, but there was a tolerable variety of trees, though rather scanty. Besides prickly underwood of talhas, there were principally the hajilíj or bíto (Balanites Ægyptiaca), the selím, the kurna, the serrákh, and the gherret or Mimosa Nilotica. Farther on, a short time before we came to the village Kalíkágorí, I observed a woman collecting the seeds of an eatable Poa, called “kréb” or “kashá,” of which there are several species, by swinging a sort of basket through the rich meadow ground. These species of grasses afford a great deal of food to the inhabitants of Bórnu,[30] Bagírmi, and Wadáÿ, but more especially to the Arab settlers in these countries, or the Shúwa; in Bórnu, at least, I have never seen the black natives make use of this kind of food, while in Bagírmi it seems to constitute a sort of luxury even with the wealthier classes. The reader will see in the course of my narrative, that in Mas-eña I lived principally on this kind of Poa. It makes a light palatable dish, but requires a great deal of butter.

After having entered the forest and passed several small waterpools, we encamped near one of these, when the heat of the sun began to make itself felt. This district abounded in mimosas of the species called gherret, úm-el-barka, or “kingar,” which affords a very excellent wood for saddles and other purposes, while the coals prepared from it are used for making powder. My old talkative, but not very energetic companion Bu-Zéd, was busy in making new pegs for my tent, the very hard black ground of Bórnu destroying pegs very soon; and in the meantime, assisted by Hosén ben Hár, gave me a first insight into the numerous tribes living in Kánem and round the bahar-el-ghazál. The fruits of the gherret, which in their general appearance are very like those of the tamarind-tree, are a very important native medicine, especially in cases of dysentery, and it is most probably to them that I owed my recovery when attacked by that destructive disease during my second stay in Sókoto in September, 1854. The same tree is essential for preparing the water-skins, that most[31] necessary article for crossing the desert. The kajíji was plentiful in this neighbourhood. The root of this little plant, which is about the size of a nut, the natives use in the most extensive way for perfuming themselves with.

Late in the afternoon we continued our journey through the forest, which was often interrupted by open patches. After having pursued the path for some miles we quitted it, and travelled in a more easterly direction through a pleasant hilly country, full of verdure, and affording pasturage to a great many cattle, for the Kánembú, like the Fúlbe, go with their herds to a great distance during certain seasons of the year; and all the cattle from the places about Ngórnu northwards is to be found in these quarters during the cold season. But not being able to find water here, we were obliged to try the opposite direction, in order to look for this element so essential for passing a comfortable night. At length, late in the evening, traversing a very rugged tract of country, we reached the temporary encampment, or berí, of a party of Kánembú with their herds, whilst a larger berí was moving eastward. Here also we were unable to find water, and even milk was to be got but sparingly.

Monday, 15th.Before we were ready to move, the whole nomadic encampment broke up; the cattle going in front, and the men, women, and children following with their little household on asses. The[32] most essential or only apparatus of these wandering neatherds are the tall sticks for hanging up the milk to secure it; the “sákti” or skins for milk and water, the calabashes, and the kórió. The men are always armed with their long wooden shields, the “ngáwa fógobe,” and their spears, and some are most fantastically dressed, as I have described on a former occasion. After having loaded our camels, and proceeded some distance, we came to the temporary abode of another large herd, whose guardians at first behaved unfriendly, forbidding our tasting a drop of their delicious stuff; but they soon exchanged their haughty manners for the utmost cordiality, when Mʿadi, an elder brother of Fúgo ʿAli, our friend in Maduwári, recognised me. He even insisted on my encamping on the spot, and staying the day with him, and it was with difficulty that he allowed me to pursue my march, after having swallowed as much delicious milk as my stomach would bear. Further on we joined the main road, and found to the left of it a handsome pool of muddy water, and filled two skins with it. Certainly there is nothing worse for a European than this stagnant dirty water; but during the rainy season, and for a short time afterwards, he is rarely able to get any other.

Soon after I had another specimen of the treatment to which the natives are continually exposed from the king’s servants in these countries; for, meeting a large herd of fine sheep, my horseguard managed to lay hold of the fattest specimen of the whole herd, notwithstanding[33] the cries of the shepherd, whom I in vain endeavoured to console by offering him the price of the animal. During the heat of the day, when we were encamped under the scanty shade of a few gáwo, my people slaughtered the sheep; but, as in general, I only tasted a little of the liver. The shade was so scanty, and the sun so hot, that I felt very weak in the afternoon when we went on a little.

Tuesday, Sept. 16th.I felt tolerably strong. Soon after we had started, we met a great many horses which had been sent here for pasturage, and then encountered another fish kafla. My horseman wanted me all at once to proceed to the town of Yó, from whence he was to return; and he continued on without stopping, although I very soon felt tired, and wanted to make a halt. The country, at the distance of some miles south from the komádugu, is rather monotonous and barren, and the large tamarind-tree behind the town of Yó is seen from such a distance that the traveller, having the same conspicuous object before his eyes for such a length of time, becomes tired out before he reaches it. The dúm-palm is the principal tree in this flat region, forming detached clusters, while the ground in general is extremely barren.

Proceeding with my guardian in advance, we at length reached the town, in front of which there is a little suburb; and being uncertain whether we should take quarters inside or outside, we entered it. It consisted of closely-packed streets, was extremely hot, and exhaled such an offensive smell of dried fish, that[34] it appeared to me a very disagreeable and intolerable abode. Nevertheless we rode to the house of the shitíma, or rather, in the full form, Shitíma Yóma (which is the title the governor bears), a large building of clay. He was just about taking another wife; and large quantities of corn, intended as provision for his new household, were heaped up in front of it.[5] Having applied to his men for quarters, a small courtyard with a large hut was assigned to us in another part of the town, and we went there; but it was impossible for me to make myself in any way comfortable in this narrow space, where a small gáwo afforded very scanty shade. Being almost suffocated, and feeling very unwell, I mounted my horse again, and hastened out of the gate, and was very glad to have regained the fresh air. We then encamped about 600 yards from the town, near a shady tamarind-tree; and I stretched my feeble limbs on the ground, and fell into a sort of lethargy for some hours, enjoying a luxurious tranquillity;[35] I was so fatigued with my morning’s ride, that I thought with apprehension on what would become of me after my companions had joined me, when I should be obliged to bear fatigue of a quite different description.

As soon as I felt strong enough to rise from my couch, I walked a few paces in order to get a sight of the river or “komádugu.” It was at present a fine sheet of water, the bed being entirely full, “tsimbúllena,” and the stream running towards the Tsád with a strong current; indeed, I then scarcely suspected that on another occasion I should encamp for several days in the dry bed of this river, which, notwithstanding the clear and undoubted statements of the members of the former expedition with regard to its real character, had been made by Capt. W. Allen to carry the superfluous waters of the Tsád into the Kwára. The shores of the komádugu near this place are quite picturesque, being bordered by splendid tamarind-trees, and “kínzim,” or dúm-palms, besides fine specimens of the acacia tribe on the northern shore. At the foot of the tamarind-trees a very good kind of cotton is grown, while lower down, just at this season of the year, wheat is produced by irrigating regularly laid-out grounds by way of the shadúf or “lámbuna.” Cotton and small quantities of wheat are the only produce of this region, besides fish and the fruit of the Cucifera or dúm-palm, which forms an essential condiment for the “kunú,” a kind of soup made of Negro millet; for the place is entirely destitute[36] of any other Cerealia, and millet and sorghum are grown only to a small extent. Cattle also are very scarce in Yó; and very little milk is to be procured. Fish is the principal food of the inhabitants, of which there are several very palatable species in the river, especially one of considerable size, from eighteen to twenty inches long, with a very small mouth, resembling the mullet.

I saw also a specimen of the electric fish, about ten inches long, and very fat, which was able to numb the arm of a man for several minutes. It was of an ashy colour on the back, while the belly was quite white; the tail and the hind fins were red. Mr. Overweg made a slight sketch of one.

During the night a heavy gale arose, and we had to fasten the ropes attached to the top of the pole; but the storm passed by, and there was not a drop of rain; indeed the rainy season, with regard to Bórnu, had fairly gone by.

Wednesday, Sept. 17th.Enjoyed in the morning the scenery and the fresh air of the river. Men were coming to bathe, women fetching water, and passengers and small parties were crossing the river, swimming across with their clothes upon their heads, or sitting on a yoke of calabashes with the water up to their middle. A kafla or “karábka” of Tébu people from Kánem had arrived the day before, and were encamped on the other side of the river, being eager to cross; but they were not allowed to do so till they had obtained permission; for, during several months, this river or valley forms annually a sort of quarantine[37] line, whilst, during the other portion of the year, small caravans, at least, go to and fro at their pleasure.

The only boat upon the water was a mákara, formed by several yokes of calabashes, and of that frail character described by me in another part of this work, in which we ourselves were to cross the river. Unfortunately it was not possible to enjoy quietly and decently the beautiful shade of the splendid tamarind-trees, on account of the number of waterfowl and pelicans which reside in their branches.

On removing some of my luggage, I found that the white ants were busy destroying, as fast as possible, my leather bags and mats; and we were accordingly obliged to remove every thing, and to place layers of branches underneath. There are great numbers of ants hereabouts; but only moderately sized ant-hills are seen; nothing like the grand structures which I afterwards saw in Bagírmi.

Thursday, Sept. 18th.About two hours after midnight Mr. Overweg arrived, accompanied by one of the most conspicuous of the Welád Slimán, of the name of Khálef-Allah, announcing the approach of our little troop; which did not, however, make its appearance until ten o’clock in the morning, when the most courageous and best mounted of them galloped up to my tent in pairs, brandishing their guns. There were twenty-five horsemen, about a dozen men mounted upon camels, and seven or eight on foot, besides children. They dismounted a little to the east of our[38] tents, and formed quite an animated encampment; though of course quarrels were sure to break out soon.

Feeling a little stronger, I mounted with my fellow-traveller in the afternoon, in order to make a small excursion along the southern shore of the river, in a westerly direction. The river, in general, runs from west to east; but here, above the town, it makes considerable windings, and the shore is not so high as at the ford. The vegetation was beautiful; large tamarind trees forming a dense shade above, whilst the ground was covered with a great variety of plants and herbs just in flower. On the low promontories of the shore were several small fishing villages, consisting of rather low and light huts made of mats, and surrounded by poles for drying the fish, a great many of which, principally of the mullet kind, were just suspended for that purpose. Having enjoyed the aspect of the quiet river-scenery for some time, we returned round the south side of the town. The ground here is hilly; but I think the hills, though at present covered with verdure, are nothing more than mounds of rubbish formed in the course of time round the town, which appears to have been formerly of greater extent.

Friday, Sept. 19th.Overweg and I, accompanied by Khálef-Allah and a guide, made an excursion down the river, in order, if possible, to reach its mouth; but the experiment proved that there is no path on the southern shore, the track following the northern bank: for on that side, not far from the mouth, lies a considerable Kánembú place called Bóso, though, in the present weak state of the Bórnu kingdom, much exposed to[39] the incursions of the Tawárek. Having penetrated as far as a village, or rather a walled town, named Fátse, the walls of which are in a decayed state, and the population reduced to a dozen families, we were obliged to give up our intended survey of the river. As for myself, I was scarcely able to make any long excursion; for, on attempting to mount my horse again, I fainted, and fell senseless to the ground, to the great consternation of my companions, who felt convinced my end was approaching. We therefore returned to our encampment. In the evening I had a severe attack of fever.[6]

Saturday, Sept. 20th.It had been determined the day before that we should cross the river to-day, and the governor’s permission had been obtained; but as the vizier’s messenger had not yet arrived, we decided upon waiting another day. Feeling a little better, I made a rough sketch of the town, with the dúm-palms around it, and prepared myself, as well as I was able, for the fatiguing march before me. We had a good specimen to-day of the set of robbers and freebooters we had associated with in order to carry out the objects of the mission. The small Tébu caravan, which I mentioned above as having arrived from Kánem, and which had brought the news that the[40] people of Wadáy had made an alliance with all the tribes hostile to the Welád Slimán, in order to destroy the latter, had not been allowed to cross the river until to-day. They were harmless people, carrying very little luggage (chiefly dates) upon a small number of oxen; but as soon as they had crossed, our companions held a council, and, the opinion of the most violent having gained the upper hand, they fell upon the poor Tébu, or Kréda, as they call them, and took away all their dates by force. The skins were then divided; and the greater part of them had already been consumed or carried away, when an old Arab arrived, and, upbraiding his companions with their mean conduct, persuaded them to collect what remained, or that could be found, and restore it to the owners. In the evening the vizier’s messenger arrived, and the crossing of the river was definitively fixed for the next day.

Monday, Sept. 22nd.Rose early, in order to get over in time, there being no other means of crossing than two mákara, each consisting of three yokes of calabashes. The camels, as is always the case, being the most difficult to manage, had to cross first; and after much trouble and many narrow escapes (owing principally to the unevenness of the bottom of the valley, the water-channel having formed a deep hollow—at present from ten to eleven feet deep—near the southern shore, while in the middle the bottom rises considerably, leaving a depth of only six or seven feet) they all got safely over, and were left to indulge in the foliage of the beautiful mimosas which[41] embellish the northern border of the river. The horses followed next, and lastly we ourselves with the luggage.

About nine o’clock in the morning I found myself upon the river on my three-yoked “mákara,” gliding through the stream in a rather irregular style of motion, according as the frail ferry-boat was drawn or pushed by the two black swimmers yoked to it. It was a beautiful day, and the scenery highly interesting; but, having been exposed to the sun all the morning, I was glad to find a little shade. When all the party had successively landed, and the heat of the day had abated, we loaded our camels and commenced our march. We were now left entirely to the security and protection which our own arms might afford us; for all the country to the north of the komádugu has become the domain of freebooters, and though nominally sheikh ʿOmár’s dominion stretches as far as Berí, and even beyond that place, nevertheless his name is not respected here, except where supported by arms.

The country through which we were passing bore the same character as that for some miles round the capital; a very stiff, black soil, clothed with short grass and a few trees far between. Having encountered a flock of sheep, our friends gave chase; and after they had laid hold of three fat rams, we decided to encamp.

Tuesday, Sept. 23rd.For the first four hours of our march the character of the surrounding country remained nearly the same; it then opened, and became[42] better cultivated; and soon after we saw the clay walls of Báruwa, though scarcely to be distinguished, owing to the high mounds of rubbish imbedding them on all sides. Near the south-west gate of the town the road leads over the high mound (which destroys entirely the protection the wall might otherwise afford to the inhabitants), and lays its whole interior open to the eyes of the traveller. It consists of closely packed huts, generally without a courtyard, but shaded here and there by a mimosa or kúrna, and affords a handsome specimen of a Central African dwelling-place. The inhabitants, whose want of energy is clearly seen from the nature of the mounds, do not rely upon the strength of their walls; and, to the disgrace of the sheikh of Bórnu, who receives tribute from them, and places a governor over them, they likewise pay tribute to the Tawárek. They belong in general to the Kánembú tribe; but many Yédiná, or Búdduma, also are settled in the town. Their principal food and only article of commerce is fish, which they catch in great quantities in the lake, whose nearest creeks are, according to the season, from two to three miles distant, and from which they are not excluded, like the inhabitants of Ngórnu and other places, on account of their friendly relations with the warlike pirates of the lake. As for corn, they have a very scanty supply, and seem not to employ the necessary labour to produce it, perhaps on account of the insecure state of the country, which does not guarantee them the harvest they have sown. Cotton they have none, and are obliged to barter their fish for cotton[43] strips or articles of dress. Indeed, gábagá or cotton strips, and kúlgu, or white cotton shirts, are the best articles which a traveller, who wants to procure fish for his desert journey by way of Bílma (where dry fish is the only article in request), can take with him.

At the well on the north side of the town, which does not furnish very good water, the horsemen belonging to our troop awaited the camels. Only a few scattered hajilíj (Balanites Ægyptiaca) and stunted talha-trees spread a scanty shade over the stubble-fields, which were far from exhibiting a specimen of diligent cultivation; and I was very glad when, having taken in a small supply of water, we were again in motion. We soon left the scanty vestiges of cultivation behind us, and some bushes of the siwák (Capparis sodata) began to enliven the country. At eleven o’clock, having mounted a low range of sand-hills, we obtained a first view of the Tsád, or rather of its inundations. The whole country now began to be clothed with siwák. Having kept for about half an hour along the elevated sandy level, we descended, and followed the lower road, almost hidden by the thickest vegetation. This lower road, as well as our whole track to Ngégimi, became entirely inundated at a later period (in 1854), and will perhaps never more be trodden: in consequence, when I came this way in 1855 we were obliged to make a circuit, keeping along the sandy level nearer to the site of the ancient town of Wúdi.

Shortly afterwards we encamped, where the underwood had left a small open space, at the eastern foot[44] of a low hill. The prickly jungle was here so dense that I searched a long time in vain for a bare spot to lie down upon, when, to my great satisfaction, I found Bú-Zéd clearing me a place with his axe. The swampy shore of the lake was only about four hundred yards from our resting-place; but the spot was not well chosen for an encampment, and it was found necessary to place several watches during the night, notwithstanding which, a skin of mine, full of water, disappeared from the stick upon which it was suspended, and the Arabs tried to persuade me that a hungry hyæna had carried it off; but it was most probable that one of themselves had been in want of this necessary article of desert travelling.

Wednesday, September 24th.We continued our march through the luxuriant prickly underwood, full of the dung and footsteps of the elephant. Here and there the capparis had been cut away, and large fireplaces were to be seen, where the roots had been burnt to ashes. The tripods, of which several were lying about, are used for filtering the water through these ashes, which takes from them the salt particles which they contain. This water is afterwards boiled, and thus the salt obtained. This salt is then taken to Kúkawa by the Kánembú, whilst those who prepare it are Búdduma.

On our return from Kánem we met large numbers of this piratical set of islanders; and on my home journey in 1855, I saw them in the full activity of their labours. This salt, weak and insipid as it is, is at least of a better quality than that which the people[45] in Kótoko prepare from neat-dung. In Míltu, on the Upper Shári, or Bá-busó, salt of a tolerable quality is obtained from a peculiar species of grass growing in the river. The Músgu, as we shall see, prepare this necessary article (or at least something like it) from the ashes of the stalks of millet and Indian corn.

After we had emerged from the underwood into the open country, we passed a considerable salt-manufactory, consisting of at least twenty earthen pots. Large triangular lumps of salt were lying about, which are shaped in moulds made of clay. Several people were busy carrying mud from an inlet of the lake which was close at hand, in order to make new moulds. Keeping close along the border of the latter, and enjoying the fresh breeze which had before been kept from us by the forest, we halted early in the afternoon. A small Tébu caravan was also encamped here, no doubt with the intention of passing the night; but they did not like the neighbourhood of our friends, and, loading immediately, started off.

Our path now lay through fertile pasture-grounds, with a line of underwood to our left. It was a fine cool morning. We passed a large pool of fresh water, frequented by great numbers of waterfowl of various species. Overweg, on his fine and tall, but rather heavy and unwieldy charger, made an unsuccessful attempt to overtake a pair of kelára (Antilope Arabica? Aigocerus ellipsiprymnus?), who scampered playfully away through the fine grassy plain. At[46] nine o’clock we reached the far-famed place Ngégimi, and were greatly disappointed at finding an open, poor-looking village, consisting of detached conical huts, without the least comfort, which, even in these light structures, may well be attained to a certain degree. The hungry inhabitants would not receive anything in exchange for a few fowls which we wanted to buy, except grain, of which we ourselves, in these desolate regions, stood too much in need to have given it away without an adequate substitute.